CommentsCOVID MANDATE - Like most COVID-related safety measures, the city of Los Angeles’ newest proof-of-vaccine mandate can be analyzed to the point of disorientation.

Politically crowdsourced, modified after feedback from business and commercial property owners, it ain’t perfect. After pushback from some businesses, a significant exception was later carved out by the L.A. City Council, which for some may diminish the weight of the ordinance. It’s easy to pick nits.

But the measure should be seen for what it is at the core: one of the most far-reaching attempts by any city in the U.S. to require that people prove they’ve been vaccinated before they step into a multitude of public locations. Whatever its limitations, the effort has a chance to be effective. It needs to be monitored closely.

The timing should allow for significant measurement. With winter approaching, health experts are predicting another surge in cases of the virus, although vaccine campaigns and the vast number of people who’ve already had COVID — more than 48 million across the U.S., 4.8 million in California — are expected to knock down the severity of many of those cases.

In other words, researchers suggest, this winter isn’t likely to resemble last December and January, when COVID cases spiked massively and Los Angeles County bore the brunt of its worst effects, including record deaths.

The problem: All of the projections about a comparatively milder winter took place before the identification of the newest strain, omicron, which likely will reach the U.S. shortly. The variant has already been found in more than a dozen countries, including Canada.

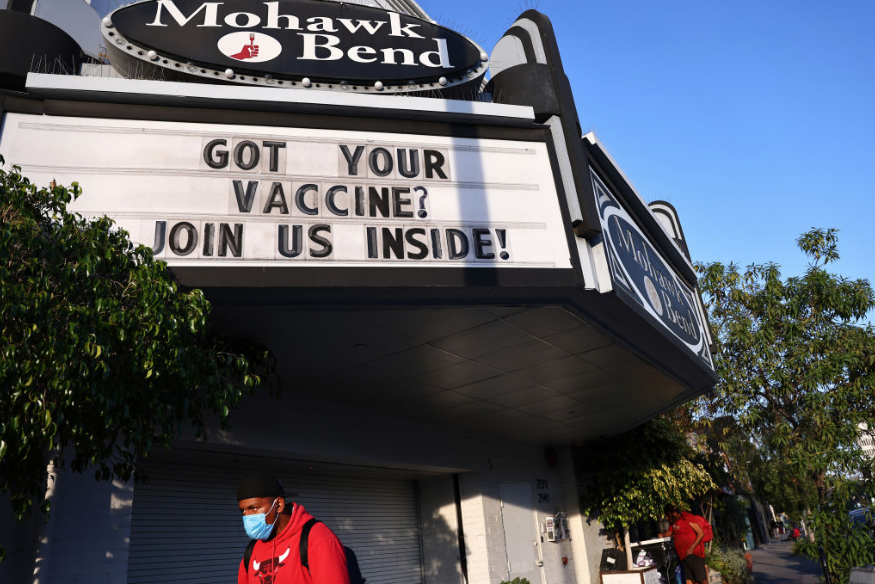

L.A.’s proof-of-vaccine requirement feels all the more prudent and timely. It extends to gyms, coffee shops, bars, hair and nail salons, museums and performance venues in addition to indoor restaurants and movie theaters.

More is unknown than known about omicron, but global health leaders are concerned that the strain may prove more resistant to the current vaccines. It is a reminder of the complications of the delta variant, which spread roughly twice as quickly as earlier strains of COVID, amplifying the task of health officials and local agencies trying to contain it.

In that context, Los Angeles’ proof-of-vaccine requirement feels all the more prudent and timely. It’s also far reaching, extending to gyms, coffee shops, bars, hair and nail salons, museums and performance venues in addition to indoor restaurants and movie theaters. In general, patrons must show one of several forms of verification that they’ve been vaccinated in order to go inside, with alternatives possible for some businesses and city offices.

But there are important limitations to bear in mind as the ordinance gets analyzed and we find out what worked and what didn’t. First, it’s a city rule, not countywide, and that is significant when applied to the sprawling L.A. region. The population of the city of Los Angeles is just south of 4 million, while the county has more than 10 million residents.

Second, there are loopholes in the city regulation. Although the rule technically went into effect three weeks ago, its enforcement was delayed until Nov. 29, or just after Black Friday and Thanksgiving weekend sales went off as usual all over the city. And the Los Angeles City Council amended the rule only a few days after it was initially rolled out, voting unanimously — and without comment — to exempt malls, whose owners suggested they’d have trouble with logistics because of their multiple points of entry.

Finally, there’s no question that enforcement of vaccine rules on a scale as large as L.A.’s is inherently problematic. There isn’t enough city staff to even consider regular checks of area businesses to see if they’re complying; it’s more likely that the process will be driven either by consumer complaints or more random enforcement efforts.

* * *

Businesses that ignore the rule face a warning first, then a $1,000 fine that can escalate to $5,000 upon repeated infractions. Clearly, there’s no overarching goal to punish the same L.A. businesses that have endured lockdowns and severe restrictions for the better part of two years. Rather, the idea is to limit the spread of a deadly virus to whatever extent is possible — and in the main, that involves asking businesses to do what’s in their own best interest by adhering to fairly straightforward requirements for entry.

Another winter surge could well force other municipal agencies into decisions they’ve either postponed or never wanted to implement in the first place.

The effort by Los Angeles is not a first; San Francisco, for example, enacted similar rules in August. But both cities remain well outside the norm in the U.S., at least for now. Another winter surge, if it lands as predicted, could well force other municipal agencies into decisions they’ve either postponed or never wanted to implement in the first place.

In those worst months of last winter, December and January, Los Angeles was devastated. Ambulances circled hospitals, trying to find emergency rooms that would accept their COVID patients. Some facilities nearly ran out of oxygen, and intensive care units were stretched well beyond their capacities. Countywide, more than 6,400 people died, a figure that was 137% above the highest death count for any previous month.

Aggressive vaccination efforts and the more recent booster shots may well prevent a repeat of that nightmare, but only if those vaccinations are made to matter. That is precisely why L.A.’s newest effort demands to be watched and — if successful — deserves to be emulated.

(Mark Kreidler is a California-based writer and broadcaster, and the author of three books, including Four Days to Glory. This story was first featured in Capital and Main.)