Comments

iAUDIT! - In a previous column, I mentioned the high compensation some nonprofit executives make, and how that compensation has precipitously increased over the past few years. But I failed to mention wages at the other end of the spectrum, those earned by front-line homelessness workers; the field outreach and shelter case workers who meet the unhoused where they are. These are the people the community depends on to work with homeless people under immensely challenging conditions; in encampments under freeways and in shelters teeming with troubled souls. They do not have the luxury of discussing abstract social theories from a plush corporate office, and they rarely see inside of the halls of power.

Front-line workers are at the epicenter of a staffing crisis in homelessness programs. Homelessness agency leaders often cite difficulties attracting and retaining qualified employees as a major impediment to successful interventions. Because of complex hiring rules and a parallel shortage of human resources staff, many public agencies can take months to hire case workers. Both public and nonprofit organizations are in a constant state of recruitment as employees quit almost as quickly as they are hired. Obviously, this has a negative effect on the unhoused themselves, since they lose the benefit of working with the same case worker as they navigate the shelter-service-housing system. To quote a respondent to a survey conducted by advocacy groups, “The case managers are unprofessional. I’ve had five different case managers because there’s so much turnover”. That same survey showed more thana one-third of Inside Safe participants don’t know who their case managers are.

What is less often discussed by leaders is the paltry wages many organizations pay their front-line workers. A 2023 RAND study described the consequences of the low wages paid to many employees. The report said workers need to make at least $64,000 per year to pay the rent for a one-bedroom apartment and $82,000 for two-bedrooms, but most front-line workers make between $40,000 and $60,000 per year. Someone is considered rent-burdened when they pay 30 percent or more of their salary for housing. Obviously, someone making $60,000 per year cannot afford an apartment of their own. The personal cost of the wage crisis was detailed in a May 2023 L.A. Times article, where one front-line worker said he has to live with 11 other people in a rented home to afford the rent. Taking a broader view, the wage-rent gap is the reason LA’s Pico-Union and Pico-Robertson areas are among the nation’s most overcrowded, as low-wage workers sleep two or more to a room to avoid homelessness—this is the true housing crisis.

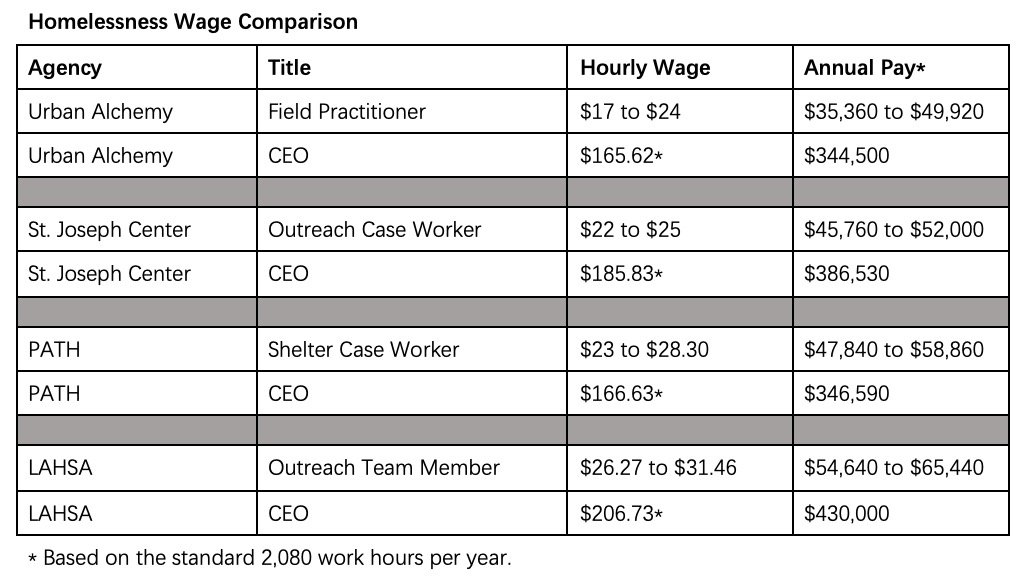

To associate numbers with the stories about low wages, I looked at four agencies’ employment opportunities for front-line employeess: LAHSA, Urban Alchemy, PATH, and St. Joseph Center. In most cases, the hourly pay was surprisingly low given the importance of the work. Then I compared those wages to the chief executives’ pay to give readers an idea of the differences in compensation.

As you can see, only LAHSA pays its front-line workers wages sufficient to cover the rent for a one-bedroom apartment—and only at the top of range, where new employees rarely start. St. Joseph Center and PATH prefer candidates with a Bachelor’s degree. LAHSA has similar preferences, but says it requires applicants with the proper experience and education. Urban Alchemy is the exception, since it states 90 percent of its entry-level hires are people with lived homelessness or carceral experience, (although it appears that experience isn’t worthy of a living wage). LAHSA’s team members make decent wages and have the added value of the generally good benefits packages available in the public sector, but they still make only about 15 percent of the CEO’s pay. These agencies expect a lot out of their candidates given the low pay.

Certainly, the wage gap between nonprofit front-line workers and executives is nowhere near that in the corporate world, where CEO’s make as much as 400 times or more as their employees. But for-profit corporations and nonprofits exist for two very different reasons. Private sector companies function to make money for themselves and their shareholders. While corporate pay is an important social and economic issue, it has nothing to do with nonprofit or public sector pay. Nonprofits and public agencies should work for the greater good. Speaking as a career civil servant, one does not enter public service to become wealthy. I was compensated well for my skills and experience as a manager, but I did not make as much as my private sector manager spouse. There are trade-offs between the two sectors (higher pay in one, generally better benefits and more stability in the other), but you’ll never get rich working in the public sector.

Giving credit where its due, one the reasons Heidi Marston, Dr. Va Lecia Adams-Kellum’s predecessor as CEO of LAHSA, resigned was that LAHSA’s Board of Commissioners ignored her repeated pleas to increase front-line worker pay and stem the tide of high turnover plaguing the agency. In a sign of the Board’s priorities, they gave Dr. Adams Kellum a 40 percent increase in compensation over Marston, from $305,000 in pay and benefits to $430,000.

The hypocrisy of the wage differential in homelessness programs goes well beyond compensation. It is the lip service leaders pay to the importance of front-line service and the reality of the low priority it is given. There is no better example of that hypocrisy than a statement from the 2023 LA Times article, where PATH’s CEO decried the lack of government funding as a reason its so hard to pay front-line workers more. That was quite a statement from the CEO of an organization that saw its budget balloon from $64.2 million in 2019 to $159.5 million in 2022, and who’s personal compensation increased 24.7 percent in those three years, well beyond the rate of inflation. The supposed shortage of public money didn’t stop her from receiving hefty wage increases, even as homelessness rose during the same period.

Specifically, the LA Times article cited lack of funding from Measure H as a reason for paying low wages, saying, “Despite the 2017 approval of the Measure H local sales tax hike to fund homelessness programs, nonprofit leaders told the researchers that they don’t receive enough government funding to raise wages”. Ignoring for the moment the inherent untruth of that statement given the flood of COVID relief money sent to local governments and nonprofits, it exposes a plausible reason many nonprofits are supporting Measure A, the November ballot initiative to double the sales tax rate dedicated to Measure H. Is it really to increase services (even though the County usually leaves millions in current Measure H money unspent), or is it really an attempt to ensure a select number of large nonprofits permanently guarantee their revenues (and high executive compensation)?

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process.)