CommentsA SPECIAL REPORT--It’s Monday afternoon in Bellflower, a small suburb in southeastern Los Angeles County, California. Juana, 34, and a neighbor from her apartment complex are watching their sons. (All names in this story have been changed to protect undocumented people’s identities.) It’s one of Juana’s two days off per week from the luxury hotel she works at in Beverly Hills as a housekeeper.

The two boys, both 3 years old, are playing on the couch in the small living room that doubles as a dining area, with a kitchen tucked into a corner. Aside from helping watch over the children, Juana’s neighbor holds a gaze through an opening in the front window curtain, and eventually spots someone outside. “That’s the man with the gas company,” she tells Juana in Spanish. “It’s fine if you want to open the door when he knocks.”

Both women are originally from El Salvador. They help one another with ordinary neighborly tasks like saving a washer in the building’s laundry room for a load of clothes. As women from Central America who are terrified of Donald Trump, they watch one another’s backs the way immigrants and refugees would under a new administration that partly came into power on the promise of mass deportations. These days, the women say, every knock on the door, every step outside, and every ride on public transit merits scrutiny.

I spent the better part of a week with Juana – morning, noon and night – to try to make sense of her life under Trump, watching her calculate and recalculate even the smallest decisions in her life.

The man at her door, it turns out, works with an energy-savings assistance project and he’s here to let Juana know she’s eligible for a free, brand-new refrigerator. He just needs to confirm she qualifies for the program, which rewards low-income residents with energy-efficient appliances. He enters the tiny one-bedroom apartment to inspect the existing refrigerator, as Juana explains there are three others living here: her husband Roberto, her 9-year-old daughter Bella and her son Bobby. The man jots down some notes and leaves.

Juana’s friend – who currently has an open asylum claim after fleeing El Salvador with her then-toddler son two years ago – is part of an informal support network that helps keep Juana safe as an undocumented immigrant in Los Angeles, the place she’s called home since shortly after arriving here in 2006. Conversations between the women persistently return to the issue of immigration; Juana’s husband, Roberto, is undocumented, while her children are both United States-born citizens.

Later, she tells me that had her friend not been there to inform her that the man wasn’t an agent with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, she wouldn’t have opened the door. Instead, she would have hidden inside all day and into the night.

ICE employs what it calls a sensitive location policy, which dictates that agents should take considerable measures to avoid enforcement actions at hospitals, schools and churches. Yet since Trump assumed office, ICE has detained a woman at a hospital, a father a few blocks from his daughters’ schools and a group of men leaving a church shelter where they were keeping warm.

“Did you hear about the young woman who entered on a visa from Argentina and talked to the press?” Juana asks me one evening. She’s referring to Daniela Vargas, who was detained by ICE moments after speaking at a news conference. Juana knows the story of every high-profile detention and deportation since Trump took office. Although ICE’s policy discourages agents from targeting people at the site of a public demonstration like the one Vargas addressed, that didn’t stop her from being detained. “It’s a risk for us to talk to reporters,” Juana reminds me.

A few weeks ago, Juana was on her way to work on a Metro train when she saw a friend’s Facebook post about ICE’s presence at Union Station – a stop she wasn’t headed toward but which, nevertheless, is on the same line she was riding. When her shift ended, she asked her friend at work for a ride back home, rather than risk the train. She avoided public transportation entirely for the next five days.

In addition to verifiable news about ICE’s enforcement, and warranted warnings from her network of supportive friends, false rumors have also taken root in Juana’s life and have caused her to drastically alter her decision-making. She’d long planned to send her daughter, Bella, to visit El Salvador for the first time, either during winter or spring break, but heard that immigration agents – with vicious dogs – were swarming LAX. Although there’s no evidence of this, the rumor alone is enough for Juana to completely avoid an airport she’s visited in the past. Juana’s fear means Bella can’t visit her parent’s homeland – at least until Trump leaves office.

Juana does have rights as an undocumented immigrant, but she’s not sure what those rights are. The labor union she belongs to holds know-your-rights workshops, but she’s terrified that if she attends, her co-workers will figure out her status. Only one friend at work knows Juana is undocumented; she fears if more find out, it could all be downhill from there.

Aside from the psychological toll the constant vigilance since Trump’s election has taken on her, Juana is also risking her physical health. While she has employer-based health insurance through Kaiser, she canceled an annual physical because the fake document (which contained her real name and birthday) she was previously using to identify herself, has expired. “There are a lot of racist people,” she tells me. “What if one of them starts questioning me about my documentation?” Although she’s been struggling with digestive issues and poor circulation, she’s willing to forgo a doctor’s visit because of her uncertainty.

I explain how she can use another form of identification to go to Kaiser, like a passport. Sometime later, she shows me her Salvadoran passport and wonders why her initial panic stopped her from thinking about using it as a different form of ID. What Juana knows about this administration hurts her – but what she doesn’t know about her rights under Trump harms her, too.

Juana came to the United States in 2006, when she was 23. El Salvador’s civil war had ended in 1992, but the vast rift between the haves and have-nots that largely fueled the war lives on – and it continues to inform the country’s violence.

Juana had done especially well in mathematics in school but her family couldn’t afford to send her to college to prepare for her dream of becoming an accountant. Instead, she worked factory jobs after graduating high school. She came to the U.S. at a time when there were no real options for her to escape poverty at home. In the decade she’s been gone, El Salvador has exploded with a kind of violence that scares her far more than the threats from Trump’s administration.

“The first tragedy we lived through was in 2011, when my mom’s older brother couldn’t pay the rent,” she says. The rent she’s referring to isn’t a payment made to a landlord, however, but payments extorted by local gangs. Her uncle was killed. Then, in 2012, a second uncle was killed because he, too, couldn’t pay the rent. That left one uncle behind, who came to the U.S. that year and was granted asylum here.

In 2013, her aunt came to the U.S. and was also granted asylum along with her two children. That year, however, Juana’s father was shot in the legs but can apparently still walk. “I can’t really tell you how well my dad is doing,” shrugs Juana. “I haven’t seen him since before he was shot.”

In 2015, her brother-in-law, an undercover cop who had helped put away several gang members, was killed after his boss set him up for a pay-off. His wife, Juana’s sister, became a target after it was rumored that she was a police informant. Her sister went into hiding along with her 11-year-old daughter before fleeing north. They were apprehended just over this side of the U.S. border but were soon released pending an asylum hearing.

But there’s no such process that Juana thinks is currently available to her – she can be an undocumented immigrant, but not an asylee. This, despite the fact her family has consistently been hunted down in El Salvador, a place she’s seen grow increasingly violent from a distance. “I can’t imagine myself back there,” she says.

Juana wakes up at 5 a.m. on her workdays, Wednesday through Sunday. Roberto does custom construction work six days a week and has Sundays off – which means the two rarely get to spend a day together. Roberto drives and has a license under California’s undocumented driver program. The license, which is part of a database, is marked to distinguish his undocumented status, but Roberto says it’s better to be licensed and insured than to fly under the radar. Juana never got a license and the car she was using for short errands started acting up recently; instead of getting it fixed, she’s opted to stop driving. It’s too risky now, anyway.

It’s still dark out and Roberto yawns while he puts his boots on. “There’s no rest here,” he tells me, adding that it’s all work and bills in the United States. He works 48 hours a week earning $12 an hour as an independent contractor. The pay could be worse but it’s challenging every April when the couple forks over their share of taxes to the government.

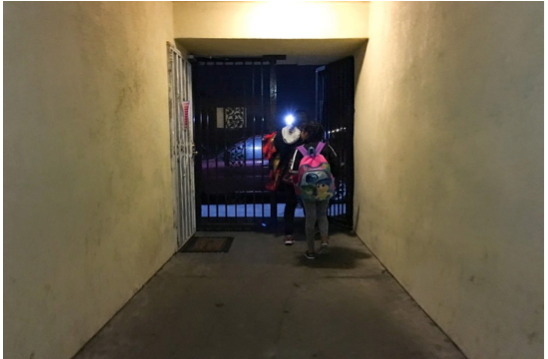

By 5:35 a.m., Roberto is warming up the car. Bella is walking with her backpack on as Juana carries a sleeping little Bobby in a blanket. They all get into the car and drive a few minutes over to the friend who will watch the children; she’ll walk Bella to school and back, and watch Bobby all day. By 6:10 a.m., Roberto drops Juana off at a rail stop.

Juana works the 8 a.m. shift cleaning rooms. She likes the union job and its perks – but as with any job, it comes with its challenges. People who can drop a thousand dollars a night on a hotel stay tend to be demanding. Some can say inappropriate things. There was a fistfight between two guests at the hotel several months ago and the police were called. She didn’t think much of it then, but is terrified of being near police since Trump got elected.

After an eight-hour shift, Juana walks back to the bus to begin her commute home, along with her friend from work – the one who knows she’s undocumented. This afternoon we’re all walking down a posh but ill-designed residential Beverly Hills street that’s become a throughway for heavy traffic, when the driver of a new sports car almost runs us over. Juana and her friend keep walking as if nothing happened. She tells me later that some Beverly Hills residents assume that because of our skin color, we’re all housekeepers and are therefore not worthy of common courtesy. Confronting the driver could result in further scrutiny from law enforcement – so rather than say anything to him, the women ignored the incident.

On the last train back home, I spot a sheriff’s deputy quickly board the car in the front of us. As soon as I let her know, Juana calmly puts her phone away and tries to distinguish the deputy through the shadows caused by the sun beginning to set on Los Angeles. For the next three stops, Juana trains her eyes on him without flinching. If I didn’t know what she was doing, I’d guess she was zoning out. She’s not.

When we detrain, Juana asks me to look back and confirm the deputy’s not following us. He’s not, I assure her. She explains she was extremely alarmed because he was alone when he should have been with a partner, since that’s how they always patrol railcars. Even for people terrified of law enforcement, one deputy shouldn’t garner more trepidation than two deputies, but in Juana’s case, it makes sense. There was something out of the ordinary and it required closer examination – this time, her complete attention to make sure the deputy wasn’t an ICE agent.

Immigration enforcement is a system – abstract and difficult to put your finger on. Sure, Juana fears the system, but that fear has also caused her to fear individuals, too: the obliging appliance man, the imaginary Kaiser receptionist, the obnoxious sports car driver – they all present a potential danger to an undocumented woman surviving the Trump era.

(Aura Bogado is a writer based in Los Angeles. She has written for the Guardian, Teen Vogue, Mother Jones and the Nation. This piece was co-produced by The American Report and Capital and Main.)

-cw

Explore

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

21

Mon, Apr