CommentsENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE-Los Angeles County took a step toward a complete ban on oil and gas production within its borders after the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved on Wednesday a motion to phase it out on unincorporated land. It’s the largest urban area in the country to declare such a ban, which will impact over a thousand active wells.

County Supervisor Holly Mitchell co-authored the motion, which cites a growing body of research linking proximity to oil production wells and health problems including low birth weights, cardiovascular disease and respiratory problems. During the board meeting, Mitchell said that nearly 73% of county residents living near wells are people of color.

While introducing the motion, she also noted the larger implications for the climate.

“Oil and gas drilling contributes to the climate crisis, which we bear witness to each and every day,” Mitchell said. A recently released report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change showed that humanity has “a short window of time to curb our fossil emissions to prevent a worse fate for future generations,” Mitchell added.

The board also passed a second motion directing the county to implement recommendations from its Just Transition to Clean Energy Task Force, including further study of how the county’s oil and gas workers would be impacted. About 30,000 people work in county oil fields, though not all of them live in the county.

In passing the motion, which designates existing oil and gas wells as no longer valid under current zoning law, the county instructed the director of regional planning, Amy Bodek, to report in 120 days how she will contract an expert to conduct an amortization study of drilling sites in unincorporated parts of the county to wind them down. Amortization means oil companies would be allowed to make up at least some of their investments on the banned wells.

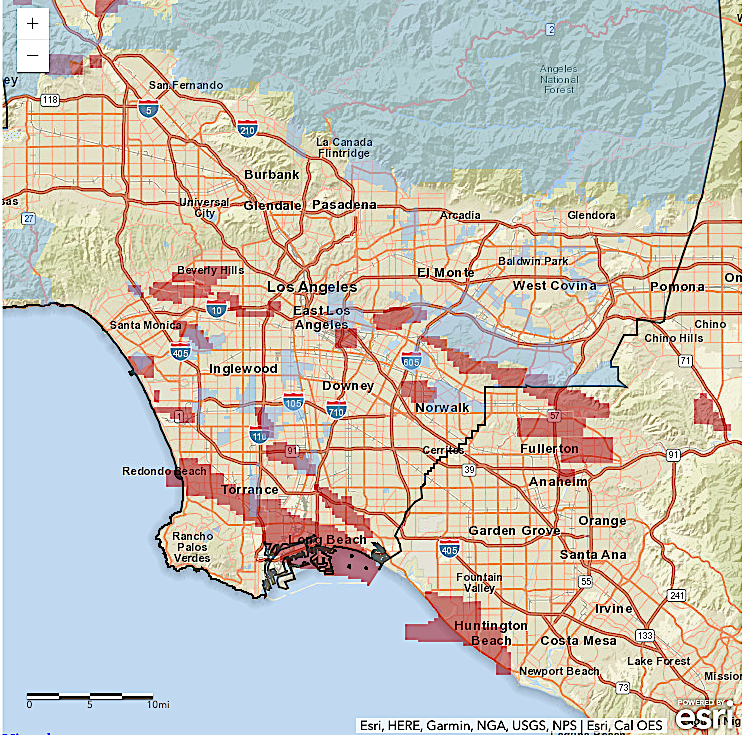

Last year the county found there were 1,046 active wells, 637 idle wells and 2,731 abandoned wells in unincorporated areas. There are thousands more located in the cities of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and elsewhere; a county attorney couldn’t confirm whether the ban would apply to wells in incorporated areas.

Some portions of at least two dozen active oil fields that overlap with unincorporated areas will be impacted by the ban.

It’s also the complete opposite approach from that of Kern County, which voted earlier this year to blanketly approve all new oil and gas development. Most of the state’s oil and gas is produced there, with Los Angeles County a distant second.

As of 2019, over 500,000 residents of LA County lived less than a quarter mile from an active oil drilling site. In addition to the more than 1,000 active wells in the county, hundreds more idle wells, which can leak carcinogens, sit near homes, schools and hospitals at a distance associated with illnesses in nearby residents.

Among them is Wendy Miranda, who lives in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Wilmington with her family. The Wilmington Oil Field is the most productive in the county, though wells there may not be affected by the county’s action.

Miranda enjoyed running track in high school but has since developed asthma, something she says is possibly related to two idle oil wells close to her home, though she’s also exposed to pollution from oil refineries, traffic pollution and diesel fumes from heavy trucks.

Her mother needs to use a nebulizer multiple times a day, and many of her friends grew up with asthma.

“I now have to carry my inhaler with me all the time,” says Miranda, a graduate student studying public health and human planning at UCLA and an intern with Communities for a Better Environment. “A lot of unincorporated areas in the county are communities just like Wilmington, people who are facing these same impacts.”

Miranda’s personal observations are supported by a recently published study by researchers at the University of Southern California that suggests living near urban oil drilling sites with both active and idle wells is significantly associated with reduced lung function in South Los Angeles.

The vote by the board of supervisors represents another blow to the industry’s local influence. Production in the Los Angeles basin fell by 18.8% between 2006 and 2016, according to a city report. Yet, there were still 68 active oil fields in the county as of 2018.

Among them is the Inglewood Oil Field. It is managed by Sentinel Peak Resources and produced almost 1.9 million barrels of oil in 2019. The field straddles the county and Culver City, which voted in July to phase out oil production on its portion of the field; the county’s move now means the entire field is slated for a shutdown.

In April, a pipeline owned by another company, E&B Natural Resources, leaked over 1,600 gallons of oil in the Inglewood field. The cleanup was swift, but environmentalists seized on the spill as an example of the industry’s clear and direct harm to surrounding communities.

The spill also brought into focus powerful industry players with ties to the county. The CEO of E&B Natural Resources, Steve Layton, is the board chairman of the California Independent Petroleum Association, one of two oil lobbying groups in the state. And Jeremy Vanderziel, who has worked as coastal asset manager for Sentinel Peak Resources, is on CIPA’s executive committee.

The lobbying group recently declared bankruptcy after a judge compelled it to pay more than $2 million in attorneys’ fees to environmental groups and the city of Los Angeles. The two had reached a settlement that included stricter rules on oil drilling near homes in places like South Los Angeles and Wilmington. CIPA then sued both the city and the environmental groups, arguing its members’ rights to due process had been violated.

In a statement, CIPA CEO Rock Zierman defended the group’s legal actions and said the attorneys’ fees cost more than its annual operating budget. He also criticized the county oil ban and predicted it would result in California importing more oil from Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Ecuador because of demand from refineries.

“Foreign production is unregulated, exceedingly polluting and dangerous to our environment,” Zierman wrote in a letter on behalf of CIPA submitted to the county before the board vote.

Martha Argüello, an environmentalist, co-chair of the STAND-L.A. Coalition and executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility Los Angeles, says she expects the industry to retaliate against the county’s vote, but such threats pale in comparison to those posed by climate change.

“We see this as a local air pollution issue that has long term climate impacts, because we know to address the climate crisis, we need to keep fossil fuels in the ground and have an equitable transition for workers in those industries,” she says.

Argüello’s group has lobbied the city of Los Angeles for years to pass a ban on oil production. Last December, the city’s Energy, Climate Change, and Environmental Justice Committee voted to send such a motion to the city council for a full vote.

Many city council members are supportive of the idea. Seven of them sent a letter to the county supervisors ahead of Wednesday’s vote, urging their support for the motions.

“The City of Los Angeles is on a parallel path as we prepare for our own fossil-free future,” the councilors wrote. “We expect that the full City Council will adopt the committee’s recommendations later this year and declare oil and gas extraction a non-conforming use in all zones citywide, ending all new oil and gas drilling.”

If approved, the city expects an amortization period to last 20 years, according to Argüello, who is pushing for five. The county didn’t answer by publication time a question about the length of its amortization period in unincorporated areas.

(Aaron Cantu is a writer for Capital & Main which distributed this story. Ingrid Lobet contributed to this report.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.