Comments

PLANNING WATCH - With strong support from Los Angeles voters, LA’s new mayor, Karen Bass, has taken two steps to deal with homelessness. On December 12 she issued an Emergency Declaration regarding the homeless crisis. Quickly ratified by the City Council, the Emergency Declaration will subsequently require monthly City Council approvals. On December 18, Mayor Bass then issued Executive Directive 1. It expedites permits and clearances for temporary shelters and 100% affordable housing.

So far, these mostly symbolic actions have grabbed local and national headlines, but a reader asked me what the Mayor should next do to end the housing crisis? These are my answers.

- Address the underlying causes of the housing crisis, not just its symptoms. The major cause is not LA’s established permitting processes but rising poverty and economic inequality, escalating housing prices, and terminated HUD and CRA public housing programs. This is why people live on sidewalks or in tents, cars, and overcrowded apartments. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) reports that in early 2002, on any given night, there were 42,000 homeless people in Los Angeles and 69,000 in the County. Although there are alternative methodologies for calculating these numbers, there are enough vacant houses and apartments to house LA’s homeless. The revised and updated Vacancy Report concluded that Los Angeles has 93,000 vacant houses and apartments. Furthermore, 200,000 people fled Los Angeles during the Pandemic’s first year, so the number of vacant housing units has probably increased.

- Share with the public the developer-provided information that led to your recent comments on NBC’s Meet the Press. You said developers told you that it is extremely difficult to get their low-income projects approved in Los Angeles. You also said that to house 42,000 homeless people, new housing must be built in all LA neighborhoods, not only low-income areas.

This is what I would have then asked the Mayor:

- Who are the developers you met with? How many low-rent projects are they trying to build? Where are they located, and which ones were opposed by local neighborhood organizations?

- Were these stalled low-income projects privately financed, with an affordable set aside through voluntary Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) density bonuses, or were they non-profit or public sector housing that did not qualify for density bonuses?

- Did developers complain to the Mayor about low-income projects that required discretionary actions, like zone changes, to become legal?

- What other administrative barriers stymied these low-rent housing projects? Were they blocked by the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)? Did they conflict with zoning laws, most of which date back to 1946? Site-Plan Review, adopted in 1990? Other laws?

- How did these long-standing land use laws cause the recent surge in homelessness?

- Will the Bass administration propose an Inclusionary Zoning Ordinance for Los Angeles – similar to Glendale’s -- that mandates low-income units in new apartment projects?

- Will LA’s Housing Department begin inspecting and monitoring TOC-pledged low-priced units?

- Will the City establish an on-line registry of vetted low-income tenants who qualify for low-income housing?

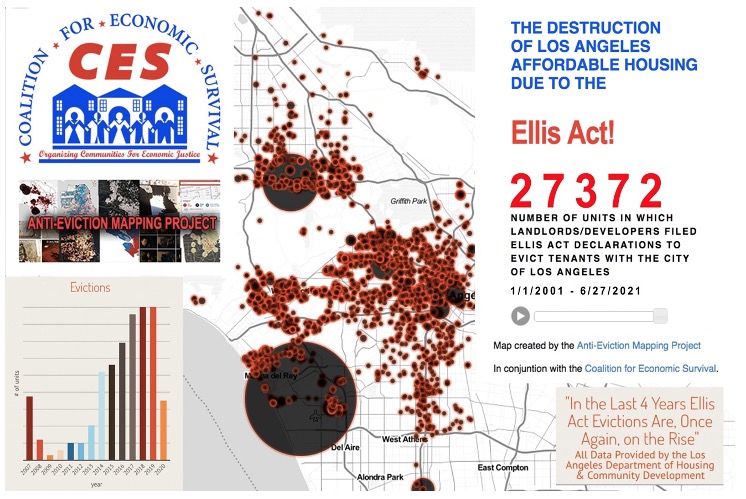

- Preserve existing low-priced housing. The best data on the loss of existing low-priced housing in Los Angeles comes from the Coalition for Economic Survival (CES). They regularly tabulate the number of rental units removed through Ellis Act evictions and demolitions. In cooperation with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, they report that between 2001 and 2021 the Ellis Act legally eliminated 27,372 housing units in LA - 3% of the city’s rent-controlled housing (which makes up roughly 75% of rental housing).

To preserve this existing low-income housing, LA’s new Mayor should take these actions:

- Use the funds generated by the voter-adopted United to House Los Angeles ULA) initiative for proactive code enforcement, especially rent stabilized (RSO) apartments. This will deter unscrupulous landlords from allowing their buildings to deteriorate to the point that tenants “self-evict.”

- The City’s Housing Department must also use ULA funds to create a multilingual 800 number, backed up by outreach counselors, to advise tenants approached by landlord agents dangling cash-for-key payments for "self-evictions.” The Housing Department would provide legal information and potential representation so targeted tenants could successfully oppose this Ellis Act run-around.

- Another source for the loss of existing low-priced housing is up-zoning. Enshrined in the City’s new Housing Element as “re-zoning”, especially in program 121- RHNA RE-ZONING, up-zoning encourages private developers to build market rate and luxury apartments at in-fill sites. This program is based on the myth that new, expensive apartments lower housing costs by increasing supply. If City Hall finally monitored its own housing programs, these data would reveal that new, expensive housing raises the cost of older housing. Once nearby landlords discover that the new buildings successfully charge high rents, they want a piece of this action.

Karen Bass’s honeymoon will soon end, and she will quickly face stark choices. Will she be the Mayor who opposes the underlying structural causes of the housing crisis? Or will she make peace with the entrenched City Hall land use policies that promote homeless-inducing speculative apartment buildings?

(Dick Platkin ([email protected]) is a former Los Angeles city planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He serves on the board of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA). Previous columns are available at https://www.citywatchla.com/index.php/cw/planning-watch-la and the CityWatchLA archives.)