Comments

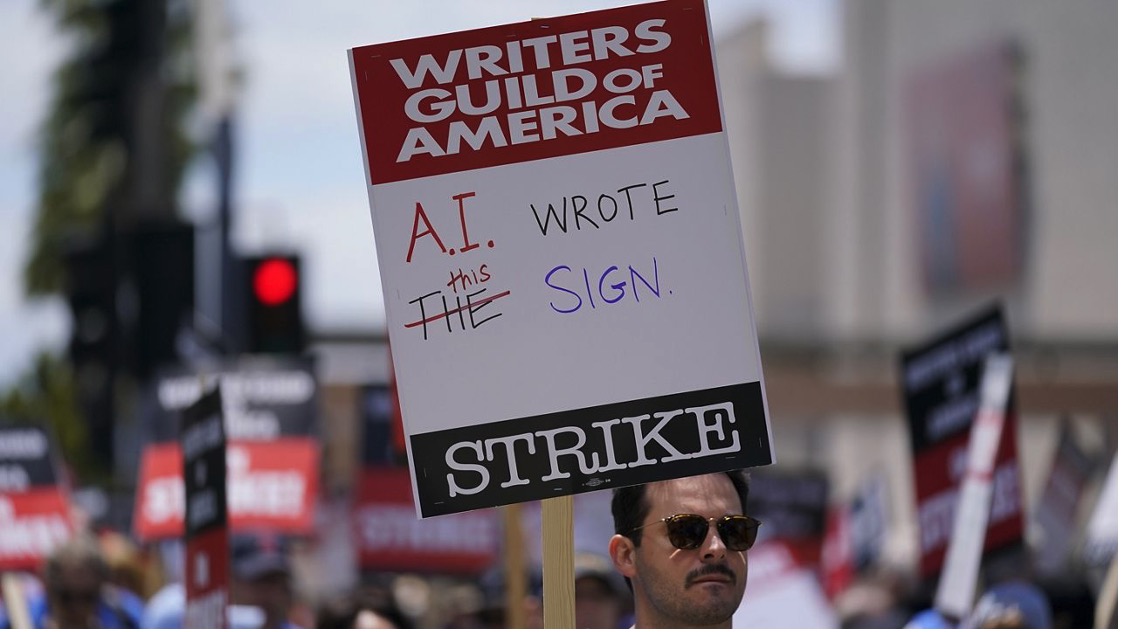

ACCORDING TO LIZ - “Fight Hollywood Greed” said the headlines criticizing the studios of not treating them fairly. And yes, there are issues that the Writers Guild of America (WGA) film and television writers are striking over that do need to be addressed.

The spokespeople for those represented by the WGA claim that it’s the power of the producers that is at fault, that they have greedily sucked everything from those who write the scripts that have created the wealth.

The question really is… who is greedier, those studios who pay for all the costs from development through distribution, or those who put digits to keyboard. And get at the most basic level, weekly pay of $5,302. That’s 330.54862 weeks at Los Angeles’ munificent minimum wage of $16.04. For one week’s work.

Oh, it can go less, all the way down to $4,063 per week but for that bargain-basement rate, the studio has to guarantee 40 weeks of work out of 52. So, $162,520 for 40 weeks of labor.

In many parts of the country, those stuck using the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, which translates into 21,669.333 hours, more than most people work in 10 years.

During the last WGA strike in 2008, the Directors Guild (DGA) made a deal with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the collective bargaining unit for the major producers, that many writers then and now feel effectively ended their ability to leverage an even better deal.

And yes, the AMPTP is almost certainly waiting for negotiations with the DGA to begin to get a better lay of the land before reconnecting with the WGA’s representatives. Contracts for both the DGA and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) expire in less than two months, on June 30th.

The contracts for IATSE locals and the Teamsters, the unions representing the below-the-line workers in television and film – the crafts – don’t expire until July 31, 2024.

However, unlike the Guilds where a very few members make very large amounts of money and significant numbers do not rely on creative work for a living and can afford to wait out the studios for the hopes of bigger occasional paydays, these below-the-line workers rely on the industry to support their families and pay their bills and mortgages.

That being said, some are showing solidarity with the writers for seeking fair and equitable wages and conditions in the new contract.

At the end of last week, Lindsay Dougherty who heads Hollywood’s Teamsters who after her re-election this past fall called on them to become “a more militant union,” announced that drivers would respect writers’ picket lines. Like armies, film crews work on their stomachs, and crafts service (snacks) and catering arrive on wheels.

This is the eighth strike by writers since the 1950s, and almost all were precipitated by technological innovations once the industry figured out how to monetize them – the advent of television and its ability to reuse material, including the broadcast of theatrical films, the introduction and expansion of pay TV, the proliferation of VCRs and videocassettes, the penetration of American television into foreign markets, the maturation of the internet and smart phones as entertainment destinations, and now streaming and the potential threats posed by AI (Artificial Intelligence).

But is what the WGA negotiators are demanding fair, and are the wages and conditions offered by the AMPTP so dreadful?

Agreed. The power of the studios IS unfair. And it was addressed once before when anti-trust lawsuits were filed by the Department of Justice in 1938 challenging the monopolistic behavior and price fixing by the major studios that culminated ten years later with the Paramount Consent Decrees banning the vertical integration of motion picture companies.

But under administrations from Nixon on, regulations to prohibit the recurrence of the monopolistic control of the majors have been chipped away by legislators funded by increasing consolidation and the growth of multinationals. Today, the power of almost every industry is entrenched to benefit the owners and reduce the leverage of the workers.

Writers may call for maintaining sustainable careers but… does anyone have that these days? Go cry on the shoulder of your Starbucks barista or Uber driver or Amazon delivery person.

What writers have on their side is the ability to craft dramatic articles complete with newsworthy quotes:

"The companies have broken this business. They have taken so much from the very people, the writers, who have made them wealthy."

The writers claim they have been betrayed: a WGA statement reports that “the studios' responses to our proposals have been wholly insufficient, given the existential crisis writers are facing. The companies' behavior has created a gig economy inside a union workforce, and their immovable stance in this negotiation has betrayed a commitment to further devaluing the profession of writing."

Don’t get me wrong – I am in strong support of unions but demands must be realistic and people must pick their battles wisely. Is this strike about rates and conditions? Or is it a creative power fight between those who write for pay and those who pay the bills?

The WGA negotiators are not only refusing offers, they are refusing to make counter offers. They rejected a 6% increase despite their members having had 3% annual increases for much of the past decade.

How most of us wish!

But streaming has now come of age just like videotapes, pay-per-view, new media and ancillary markets in the past, and must be addressed fairly. However deliberations must include the reality of who and how and how much studios actually receive in revenue which can actually be passed along to all the outreached hands from producers and directors to shareholders and… writers.

Now that it’s not a Jack Warner or Carl Laemmle who have a personal commitment to the art of movie-making running the studios, but multinationals led by Wall Street bottom-liners, the writers do have reason to be fearful of AI.

Who cares about art when profit is all that counts?

But how can producers assess the impact of AI before it happens? How can they remain competitive if non-signatories can monetize its use and they can’t?

Won’t more union writers be out of a job if producers who haven’t signed with the WGA gain the upper hand?

When major film studios announced wage deductions for writers in 1921, ten upset writers formed The Screen Writers Guild which affiliated with the Authors Guild in 1933, and with five other organizations to form the Writers Guild of America in 1954. Their focus was to ensure minimum rates along with health coverage and pensions, appropriate screen credit, and residual payments for reuse of their work.

Dues to pay for these negotiators among other services can be prohibitive especially when membership prohibits would-be writers from taking non-signatory jobs and, indeed, a certain proportion of their members are in for the prestige and the potential for an occasional big payday. Both factors inform the probability that this could be a long and painful strike.

Today’s the evil studios are a faint shadow of what they once were; the not-so-profitable subsidiaries of multinational conglomerates.

So the pain will be less for the writers and their nemesis studios, and more for the other workers and support businesses and their employees and suppliers and the cities who depend on the boost the entertainment industry gives their economy.

Watch out Los Angeles.

Fifteen years ago the 100-day Writers Guild strike cost the City’s economy more than $3 billion. Today it faces far steeper losses given the growth of the industry since 2008 to support the proliferation of distribution platforms, and the far shakier post-pandemic economy.

What about ordinary grips, carpenters and production assistants? Can they afford to go for months without pay, incur mounting debt and face losing their homes at a time when many are just starting to get on their feet after the pandemic?

What really needs to be addressed are the multinationals who now own the studios and who are forever prioritizing shareholder greed. Those are the bean-counters trying to turn writing into an less stable, gig-economy job.

But this is not new; haven’t Americans always reached for some golden apple, the lottery prize, the lawsuit settlement?

That what people watch would not be possible without the writer is true... but it is not their work alone that goes into movies and television programs.

To win, the WGA must rise above the Wall Street approach of rejecting long term sustainability for short term gains.

Right now the WGA strike is driven in part by concern over AI taking work away. Over a career spanning decades, I've seen technology vilified and then adopted. AI is just another tool and needs to be framed like a computer-assisted technical drawing, a robotic arm to protect scientists from dangerous chemicals, and heavy machinery to help with harvesting and auto construction.

What can't be allowed is for people to elevate AI above the human. AI is not a god any more than leaders of various churches or other schools of thought are.

But it is not something that can be regulated now before its impact can be assessed. Yes, it sounds like it could affect writers’ livelihoods... but so did television, VCRs and ancillary markets. The penetration of streaming is just reaching a potential that now does need to be tackled effectively but that technology started in 1995.

The credibility and its influence on the industry won’t be known for years. In the meantime, any actions in this contract may hobble the signatory producers from effectively competing with challengers who are not so constrained. Writers and producers need to work hand-in-hand to ensure that new technology does not pose an existential threat to the existing entertainment model.

As had been done many times in the past, the writers and producers need to take a step back and set up a committee to address the impact of AI over the next three years and asses the creative and financial implications to bring to the next negotiations. And, by all means, include provisions to revisit during this contract is such is warranted. But don’t destroy a whole economy based on fear.

Just because the studios and their behemoth multi-tentacles parent entities generate a lot of profit does not give the writers the right to demand excessive pay. What about the hundreds of others involved? From estimators to line producers, from directors to directors of photography, from craft service to PAs – everyone is essential to the making of a film or TV show.

Excess profits is an issue for another article, but without a steady flow of income, the studios will not fund the hundreds of writers out of which perhaps only one feature script gets made. And mandatory staffing does not make sense when every television project is different.

What about spiraling costs as every union demands more to keep up with the WGA?

Increases in a time of inflations, issues with streaming residuals (additional payments for each use in addition to the salary or purchase price paid the writer) must be addressed, but the WGA’s posturing: that companies have broken the entertainment business by stealing from the writers who made them wealthy – while categorically not addressing the studios’ concerns is equally juvenile.

And far more dangerous for the industry as a whole, and the Los Angeles economy in general.

WGA members as voiced by their negotiators are starting to sound like the denizens of George Orwell’s Animal Farm – all pigs are equal but some should be more equal than others.

Real change will require all entertainment industry professionals, all workers across the States and around the world to work together on dismantling the capitalist system at least to the level that owners and management are subject to controls to ensure that the future of the workers is as equals, not as slaves.

(Liz Amsden is a contributor to CityWatch and an activist from Northeast Los Angeles with opinions on much of what goes on in our lives. She has written extensively on the City's budget and services as well as her many other interests and passions. In her real life she works on budgets for film and television where fiction can rarely be as strange as the truth of living in today's world.)