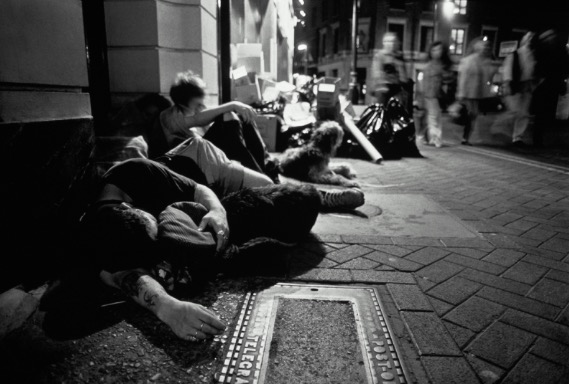

CommentsUNHOUSED IN LA - The figures on homeless youth in Los Angeles County are bleak. Statistics released Thursday estimate that more than 9,100 youth in the region lack a safe place to live.

Grimmer still is the root cause for why these youth, most of them of color, are unhoused.

Nearly two-thirds of youth and young adults up to age 24 who became homeless in 2020 listed economic hardship as the reason, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA).

“Economic hardship is often the result of a number of structural failings, including racism and other forms of prejudice, a lack of affordable housing and poverty,” says the agency’s May 2022 report, “Los Angeles Coordinated Community Plan to Prevent and End Youth and Young Adult Homelessness.” “The impacts of racism are pervasive in our community, and much of economic hardship can be traced directly back to racism.”

In short, the reason that many youth are unhoused is racism. Prejudice is what led to restrictive housing covenants preventing nonwhite people from living in many Southern California neighborhoods. This resulted in segregation, which caused properties in nonwhite neighborhoods to be devalued, as described in this Los Angeles Times story cited by LAHSA in its report.

The 128-page report details plans by Los Angeles County youth service providers to tackle youth homelessness. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded $15 million to this regional group of government agencies and nonprofit organizations for HUD’s Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program. Los Angeles County was one of 77 communities nationwide, seven of them in California, to receive this funding since the program began in 2016, in order to support community-based approaches to preventing and ending youth homelessness.

“It really motivates all these different sectors to come together to see what we have and what we don’t have,” said Simone Tureck Lee, director of housing and health at John Burton Advocates for Youth, a nonprofit that focuses on youth in foster care or who are homeless. “Where are the gaps? And where are the outstanding needs? I think the timing is right. There’s a lot of interest right now in addressing homelessness among youth compared to even a few years ago.”

* * *

The federal project offers a glimmer of hope. LAHSA’s report depicts a daunting assortment of homeless youth communities needing help. LGBTQ youth. Youth formerly in foster care. Immigrants. Unaccompanied minors. Pregnant teens. Youth impacted by gang violence. Youth struggling with substance abuse or mental health issues. Victims of domestic violence or sexual trafficking. College students.

In all, the Los Angeles County effort involves 85 cities with a total of nearly 10 million residents. Not surprisingly, the region served by LAHSA has been divided into eight parts to make it more manageable. It also helps establish that the needs of each distinct area are better targeted.

“L.A. is probably the most challenged community in the country because of its size,” Lee said. “L.A. County alone is larger than most states. The child welfare agency serves more young people than most state child welfare agencies.”

Los Angeles County and New York City, with the two largest communities of homeless youth in the country, were the only regions receiving $15 million from HUD. In Los Angeles, putting together a plan to eradicate the problem involved working with young people who have personally experienced homelessness, as required by HUD.

“As a core part of the planning and implementation of this program, both HUD and communities seeking funding have centered the voice of youth with lived homeless experience,” said HUD spokeswoman Shantae Goodloe via email. “This has been an invaluable contribution to the success of this program.”

The multifaceted plan aims to reduce homelessness by establishing better coordination among providers who connect youth to needed services; by expanding emergency, short-term and permanent housing; and by helping youth find jobs, among other things. It includes strategies as simple as creating flow charts showing youth where to go for help and working with local governments to secure abandoned properties for service providers. Though the plan calls for “ending” youth homelessness, the report acknowledges that gaps will remain even when it is fully implemented. It mentions seeking additional funding from municipalities and philanthropic partners.

* * *

Youth homelessness is often called a hidden epidemic because young people frequently continue to engage in daily activities such as going to school and hanging out with friends despite lacking safe and stable housing. Often they don’t conform to the stereotypical image that many of us might have of homeless people living on the streets or under freeway overpasses. This is why counting unhoused youth is a challenge.

“Many [youth and young adults] in need do not interact with public institutions, meaning we do not collect data on them and therefore do not know how many of them there are,” says LAHSA’s report.

Marisela Hidalgo, 21, may be among those uncounted. She hopes to go to college, but says she’s focused on getting by day to day. She frequents the library in Eagle Rock to brush her teeth and use the computers, sometimes browsing class listings at nearby community colleges, dreaming of becoming a graphic designer. She earns cash through occasional stints holding signs to advertise businesses on the street.

“It’s just a struggle trying to figure out a place to sleep each night. Sometimes, I am thinking all day about this. Other times, I know I can crash with friends or maybe stay in someone’s car that night,” said Hidalgo, who carries minimal belongings in a backpack adorned with a Pokemon keychain.

Though Hidalgo is homeless, HUD does not necessarily consider her a homeless youth under its definition. They use a complex legal definition that in general does not consider people homeless if they’re “couch surfing” (sleeping on someone’s couch), even if that living arrangement is unstable. These are issues with real life consequences for people like Hidalgo, who says she became discouraged after being turned away from a youth center that receives HUD funding.

Lack of resources and outsize needs force youth providers to make hard choices in prioritizing whom they serve. However, “Even couch-surfing youth still struggle to sufficiently sustain themselves — to a degree on par with their unsheltered peers,” according to a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health in January. The study found that youth of color and those who identified as LGBTQ, fleeing from abusive situations or inflicting self-harm were more likely to move frequently from one insecure housing situation to another. HUD’s definition does allow couch surfing for certain people facing imminent violence, but Hidalgo’s case suggests some are not receiving the services they need to access stable housing.

The definition of homelessness is important because it determines who’s eligible for HUD-funded programs. Even the Government Accountability Office has taken issue with the lack of a consistent determination of homelessness, as it made clear in its November 2021 report “Youth Homelessness: HUD and HHS Could Enhance Coordination to Better Serve Communities.” That report noted that HUD guidelines call for homeless providers to prioritize those who are chronically homeless, but most youth haven’t been homeless and disabled for a year or more. The issue is particularly crucial in Los Angeles considering the diverse communities making up the population.

What would it take to change HUD’s method of counting the unhoused? An act of Congress, it turns out.

“HUD’s homeless definition is based on the definition authorized by Congress. HUD cannot directly change the definition,” said HUD’s Goodloe. “However, expanding the homeless definition does not resolve the reality that there are simply not enough resources for the high demand for people who live in precarious housing situations.”

* * *

The latest U.S. job figures show robust growth, with employment for most people back to pre-pandemic figures. But the neediest among us require more than jobs. LAHSA’s report points to racism as a cause of the lower income and lack of accumulated wealth found among nonwhite residents. Racism that has been embodied in prejudice against immigrants, redlining, sundown towns and white flight from places like South Los Angeles.

We don’t often talk about racism as a root cause of youth homelessness, but it’s clear that its pervasiveness has an insidious impact. “From poverty and costly health conditions to the intergenerational trauma associated with substandard living conditions and increased interactions with the police, the egregious consequences of structural racism are a clear driver of economic hardship for YYA (youth and young adults) in Los Angeles County,” the LAHSA report says.

Programs proposed as part of the $15 million project are tentatively scheduled to begin Oct. 1.

It would be easy to fall into the trap of believing that youth homelessness, as vast and multifaceted as it is in Los Angeles County, is an unsolvable problem. But government officials should take advantage of the energy and ideas produced in this latest effort to combat youth homelessness. Even if it takes an act of Congress.

(Minerva Canto is a writer for Capital and Main, where this story was first published.)