CommentsJAIL TIME - Just before I started graduate school, I was arrested and spent a night in jail.

I wrote in my journal about the experience, but I put it behind me and finished my first year of graduate study in sociology without further incident.

At the start of my second year, however, I was arrested and jailed twice more.

During that fall quarter, while my peers attended graduate seminars and held discussions about this theorist or that method, my life descended into a blur of constant court appearances. Between them, I maintained my single-father duties and kept up with graduate work as best as I could. But when I was arrested a third time a few months later, I gave up fighting my cases and was expelled from my graduate program. I arranged for my son to stay with my mother, and I surrendered myself for a 180-day sentence which could be completed in 120 days with good behavior.

That might have been the end of my story, but I turned what began as a personal journal into a full ethnography of a Southern California county jail system that ultimately became the basis for my dissertation and a new book, Indefinite: Doing Time in Jail. As an academic who experienced jail with all my senses, I wrote Indefinite to toe the line between what scholars need to know about jail and what someone who’s done jail time needs to see to make the experiences I describe recognizable.

When I tell my colleagues that I conducted an ethnography in a county jail, they start talking to me about state prisons. I tell them how understudied jails are; they tell me about a recent article or book about prisons. When I tell my friends outside academia about my book, they start with congratulatory comments that evolve into concern. One of my bolder friends unmasked the rest: He wanted to know whether I’d seen or heard about “rapes in jail,” and by implication, he wanted to know whether I’d been victimized.

I told him that sexual assault is more common in prison than jail, and he revealed that he’d always thought “jail” and “prison” were completely interchangeable terms for the same place. It’s a common misapprehension; many of my colleagues are only marginally more aware that jails and prisons are different places.

In fact, justice advocates, punishment scholars, and many others hold folk knowledge about jails that alloy myth, sensational media depictions, and some measure of truth.

In some ways, the folktales are understandable. I never shared my jail experiences with friends or family. One of my close friends—who wondered but thought it rude to ask me about fights and sexual assaults in jail—is surrounded by family members who’ve done jail time: his father, an uncle, his two brothers, and his sister. None of them had described their experiences to him. (It’s worth pausing for a moment to ponder why Americans tolerate the expectation that going to jail means you’ll likely be raped.)

So what are the realities of jail time? At any given moment during the last 20 years, there have been over 700,000 persons held in jails in the U.S. Generally, several hundred thousand more persons are in custody in state and federal prisons, but jails are by far the more active organizations, with over 10 million admissions annually.

Jail time always comes first—that is, everyone in prison spent some time in jail, was convicted of a felony, and was given a sentence greater than a year. (Felony convictions with sentences less than a year are carried out in jails.)

Of course, not everyone in jail has been convicted of a crime. Most, in fact, are the “innocent until proven guilty”—at least in name. They generally constitute over 60 percent of the jail population.

As a rule of thumb, prisons are resourced for long-term holding, and jails are resourced for short-term holding.

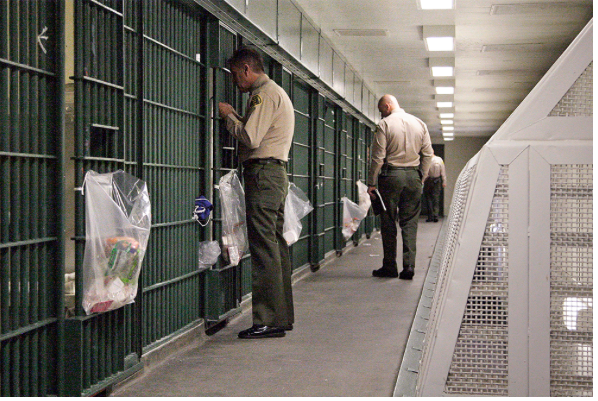

In practical terms, this means jails are harsher environments than prisons. Anyone who has been to both will attest to this: jail facilities are far shabbier and under-resourced compared with prisons. Whereas the misery of prison time might be eased with a hotplate to cook, a radio, an MP3 player, a television, skill-building programs, time on the yard, the stability of a lower turnover rate, and better food, jail cells don’t have wall outlets. If there is a working television, it is perched on a wall in the dayroom, and who controls what is watched must be worked about among everyone in the housing unit. Skill-building programs are nonexistent. The food (e.g., skim milk, an ice cream scoop of peanut butter in the middle of white bread and an apple) is as likely to kill off an appetite as it is to satisfy one. The churning of new faces and frequent shuffling between and within jails and housing units makes instability a normal aspect of life. And it is possible to go weeks at a time without smelling natural air or seeing natural light. That’s jail.

Not every jail is the same, even within the same county system. Are there gangs? Is a person held in a podular housing unit with common areas or a dormitory-style unit? How old is the jail? How do custodial staff manage overcrowding? Many county jails regularly operate more than 10 percent above capacity. Across different jails, the only constant is the set of the problems that come with doing indefinite time while innocent until proven guilty.

Prison time comes with a release date—maybe 18 months, 18 years, or natural life, but knowing your “out date” creates a goal to achieve. The mind can be oriented toward the future, and where there is a future, there is hope. Jail, with its unknowable end time, robs most of its prisoners of that hope.

Like the presumption of innocence principle, the right to a speedy trial becomes a hollow statement in jail. Nationally, the average length of stay in jail is 26 days, but in every housing unit, there is a cadre of prisoners who spend years awaiting trial or any conclusion to their cases. Two years. Four years. Nine years! If in my research I had not seen the booking numbers, indicating the year and admission number in a long succession of annual admissions, I would not have believed it.

While I met some men who were delaying trial as a legal strategy, most were anxious to go to trial. Their hopeful emotions swelled before every court appearance, only for that hope to be turned against them after their “time in court” amounted to them sitting silently in the prisoner gallery while their public defender, the assistant district attorney, and the judge spoke in legalese before issuing a continuance.

More jail time means dealing with the constant cold. It means dealing with others who have temporarily lost the ability to endure the vagaries of the jail environment and are thrusting their breakdown at everyone.

And it means more evidence of guilt. One may be awaiting trial, but the jail uniform speaks for prisoners. It conveys to all who see it that the person wearing that uniform is a “criminal” and is, therefore, deserving of punishment. The cell lights never go off, so prisoners must learn to sleep under unrelenting institutional lighting or go mad trying. One prisoner is in for shooting a BB gun in an open field, and his “celly” is in for attempted murder. Race relations and gang politics restrict where a prisoner can walk and with whom he can talk, and these conditions are more or less understood as appropriate because you are in jail.

There are more uncertainties in jail than the mind can handle. There is the indefinite nature of jail time. But also an unexpected transfer to a new jail or housing unit in the dead of the night; an unexplained lockdown; a fight; a miraculous release; canceled clothing exchanges and commissary; mealtimes moved two hours ahead or three hours behind; canceled mail and visiting hours. All jail prisoners suffer such unplanned and unexplained events, but a prisoner with a release date can reason that all this mess is temporary.

Prisoners doing indefinite time, however, have only an undefined expanse of time ahead of them. This produces a gnawing need to tie yourself to something real and knowable. In the end, the innocent until proven guilty concern themselves only with the present—the only real thing that can be controlled. For many, jail time is done moment by moment. The future is too uncertain.

To be unconvicted and in jail counts among the most demoralizing kinds of penal time a person can “do.” But let me give you the wisdom a guy gave me while in a holding cell. “In prison, you’re home. You’re just home. They try to make it comfortable for you. Jail is punishment. Prison is like working for the government. You’ll be taken care of. You just do your job, and you’ll be OK. Jail is like working at McDonald’s. You could be fired. The pay sucks. The whole thing sucks.”

(MICHAEL L. WALKER is an assistant professor in the department of sociology at the University of Minnesota. His broad research interests include punishment, race relations, and inequality. His new book, Indefinite: Doing Time in Jail, is available wherever books are sold. This article was featured in ZocaloPublicSquare.org.)