CommentsPLANNING WATCH - As sure as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, the Los Angeles Times (LAT) is a reliable member of the Urban Growth Machine, an alliance of vested interests that promote real estate speculation.

Whether cheering on the suburbanization of the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys in the 20th century or infill real estate projects in the 21st century, the Times rolls out the welcome mat for real estate speculators. But there is a catch. The paper’s writers must reconcile their employer’s devotion to real estate profiteering with a host of adverse, long-term consequences, especially homelessness. To square this circle, the reporters, editorial writers, and columnists blame personal – not social -- pathology for these unwelcome outcomes, especially mental illness and drug addiction.

Even though the paper’s circulation declined from 1,225,000 in 1990 to its current 556,000, its devotion to the real estate industry has never wavered, even when its unintended consequence, mass homelessness, increases throughout the entire Los Angeles region.

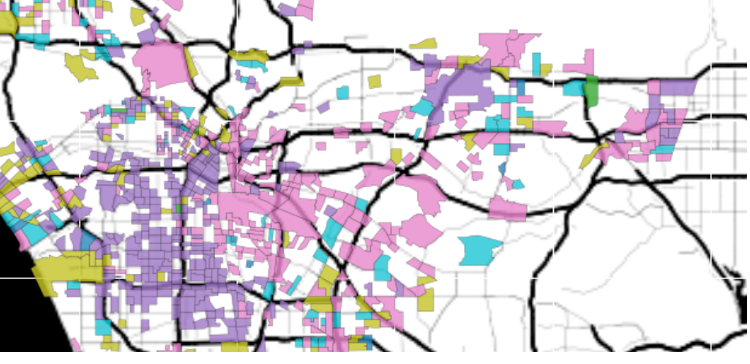

Map of homeless concentrations in the entire Los Angeles region.

This devotion to real estate construction – consistently (mis)labelled as the solution, not the cause, to the housing crisis -- was on full display in the paper’s Sunday, February 21, 2022, edition.

Everyone’s favorite LAT columnist, Steve Lopez, wrote that “Homeless effort must address mental illness.” While undeniable, better mental health services for the homeless beg a deeper question. Why don’t most people with mental illness and/or drug addiction become homeless? According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), each year one person in 20 experiences a serious mental illness, and one in 15 have both a substance use disorder and mental illness. Since the number of homeless people in the United States is about 600,000 people on any given night, and the overall U.S. population is 330,000,000, the number of people with serious mental illness and/or addiction range from 16,000,000 to 22,000,000 people. Only a small percentage of them end up in cars, shelters, or the streets.

How do most of them avoid homelessness? The answer comes down to resources, either personal or through families and friends who help the mentally ill and addicted find a place to live. Without access to these resources, the shortage of low-priced housing means that a small minority of those with severe mental illness are priced out of housing. Therefore, the solution is not only better mental health services, but also programs, like public housing, that prevent people from becoming homeless.

Another LA Times columnist, Gustavo Arrellano promotes the private repurposing of the vacant 1.6 million square foot Sears building in Boyle Heights for homeless services and shelter for 2,000 people and eventually 10,000. Like Steve Lopez’s call for better mental health services, this proposal, too, begs a critical question. Why does Los Angeles County have 66,000 homeless people, and why have these numbers continued to grow, despite ever expanding homeless services and shelters.

Part of the answer is that City’s and County’s approach to the housing crisis is to treat symptoms and ignore key structural causes, especially wage stagnation and the elimination of HUD’s public housing programs.

The editorial page of the same LAT edition also offered, “Six things the next mayor must get about homelessness.”

- “Don’t say the root cause of homelessness is mental illness and substance.” Sounds good, but the paper never bothered to list the root causes of homeless, other than saying there is a lack of housing. This claim, however, has been debunked by two studies: The Vacancy Report and the Los Angeles City Council’s Report on the Amount of Vacant, Habitable Housing Units in Los Angeles. If the homeless had enough money, they could find vacant apartments to rent in Los Angeles.

- “Talk about how you’re going to increase the housing supply in the city.” The devil is in the details, and the paper’s only detail is its endorsement of LA’s new 2021-2029 Housing Element. Beyond that the LAT admonishes mayoral candidates to explain how they would pull a rabbit out of hat, that is fund new, low-priced apartments. Unmentioned, however, are the two obvious funding mechanisms: the restoration of HUD public housing programs and the Community Redevelopment Agency’s 20 percent budget allocation for subsidized public housing.

- “Talk about how you’ll protect vulnerable renters and others from losing their housing.” Other than challenging candidates to state how they would protect renters; the paper remains silent even though the answers are easy to find. LA’s existing Rent Stabilization Ordinance is weak, and it needs to be strengthened. Vacancy decontrol should end so older apartments do not revert to market rate rents when a new tenant moves in. Likewise, the City’s 1978 cutoff date for its Rent Stabilization Ordinance should be updated. California law allows a 15 year cutoff date. If adopted, thousands of apartments built between 1978 and 2007 would then be covered by LA’s amended Rent Stabilization Ordinance.

- “Acknowledge that the City needs more permanent housing that shelter beds.” The LAT editorial only refers to repurposing hotel, motels, and apartment buildings. It never mentions more funding for Federal Section 8 housing since in LA only 400 people per year obtain Section 8 housing from an applicant pool of 600,000 Los Angeles also needs to follow the lead of the County, which has adopted an inclusionary housing ordinance. The new law requires all new apartment projects to dedicate up to 20 percent of rental units for low income tenants.

- “Don’t pander to voters by talking only about enforcement efforts.“ Local residents pound on the doors of elected officials to remove homeless encampments because City Hall’s housing programs ignore the causes of homelessness. As a result, their programs consistently fail because local cities cannot build their way out of a worsening housing crisis of their own making. Every time that public officials respond to their loudest constituents with LAPD-enforced camping bans, their real message is that their housing schemes make investors rich and the housing crisis worse.

- “Put a stop to the fragmented approach to homeless housing. The City Council has adopted a citywide approach to homelessness, the new Housing Element.” In theory LA’s new Housing Element presents a unified City Hall approach to the housing crisis, but in practice City Hall lacks coordination and monitoring to determine what works and what does not. It also has a Plan to Address the Shelter Crisis and a Homeless Strategy Committee that meets monthly to implement this plan. How these and other fragmented homeless efforts can be meshed together remains a mystery.

What we don’t know is how long the Los Angeles Times and local officials can shine on the public with repeated claims that building more market-rate housing will end homelessness. Since the evidence is accumulating that this approach increases, not reduces, homelessness, and since the LAPD can only dislocate, not jail, the homeless, the public’s skepticism is growing.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angeles city planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He serves on the board of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA) and co-chairs the Greater Fairfax Residents Association. Previous Planning Watch columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions and corrections to [email protected] .)