CommentsAT LENGTH-For most of my life racism was something people just didn’t talk about.

It was treated as something different from religion or politics, which also were not to be discussed in polite conversation. That is the case except if you grew up in a home where all of the above was discussed, which I did. It is also why most white people are ignorant of racism, it’s simply something they have not experienced.

In Los Angeles, it wasn’t really until the Watts Rebellion exploded in August of 1965 that racism came into the civic discourse and could no longer be ignored. We are reminded of this by civil rights lawyer Connie Rice who recently wrote:

“It was only after this that the McCone Commission concluded that preventing future unrest required two things: ending police mistreatment and addressing ‘the spiral of despair’ caused by entrenched poverty.”

Then in the late 1960s, the civil rights and the anti-war movements became intertwined when Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his famous speech at the Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, a year before his assassination.

In this speech, Dr. King said:

“Perhaps a more tragic recognition of reality took place when it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population.

We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.

And so we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.”

The racism that Dr. King and his successors have fought against — institutional racism or systemic racism — is perpetrated by a system that works to ensure white supremacy in all matters of life.

Just about every 27 years since the Watts Rebellion, Los Angeles has been burned by racial unrest, the latest has been less severe than the previous two but still you can almost set your calendars by it happening. Will this time be different? However, the cause is still the same today as before: police abuse and endemic poverty.

The history of racial prejudice here cannot be taken out of context of the greater history of race relations in Southern California nor the nation as a whole. It can, however, be seen as a microcosm of the greater history. Yet, it is specifically relevant to local organizers and the community at large to contextualize the contemporary situation by understanding the Harbor Area’s own special history.

What is often missing from some of this history here in California is the genocide and enslavement of the indigenous peoples first by the Spanish and then the Americanos. Several years ago, in an oil refinery in south Carson, workers digging a pipeline uncovered the remains of a mass grave that turned out to be from the pre-Yankee era.

Forensic archeologists noted that many of the skulls had what appeared to be bullet holes and that this was the scene of some violence. This may be the only historic evidence we have to date of the local crimes against people of color here, but there are even more documented cases all across California.

In the historical era of Los Angeles it is known that some of the first settlers of this city were of African ancestry and that as the city grew it became more segregated to the point that up until the late 1960’s there were restrictive covenants in deeds and titles that excluded black, Mexicans and Jews from many parts of Los Angeles, including many parts of San Pedro, all of Palos Verdes, Torrance and many parts of Long Beach.

Early in the 20th century in Southern California like elsewhere in America saw the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which enforced racial prejudice, often violently. Here in San Pedro like many towns we had our own chapter of the KKK and the building that was once their meeting hall still sits up on 10th Street.

Recently, when a new developer proposed tearing down the old brick Calvary Chapel and putting up new condos, I was the only voice to remind them of the forgotten origins of that edifice. They denied it, saying that they had done a “complete historic survey and never came across that.” I was merely expressing the perspective that if we don’t preserve the historical truth of our past, we are doing a disservice to the future. Perhaps there should be a plaque marking the spot?

They later recanted and admitted that they were mistaken.

I became aware of this hidden and forgotten history in San Pedro back when we published the first contemporary article on the union demonstration at Liberty Hill in 1923, which we published 70 years later. It was in that year that the Industrial Workers of the World, IWW or Wobblies as they were commonly known, held a waterfront strike.

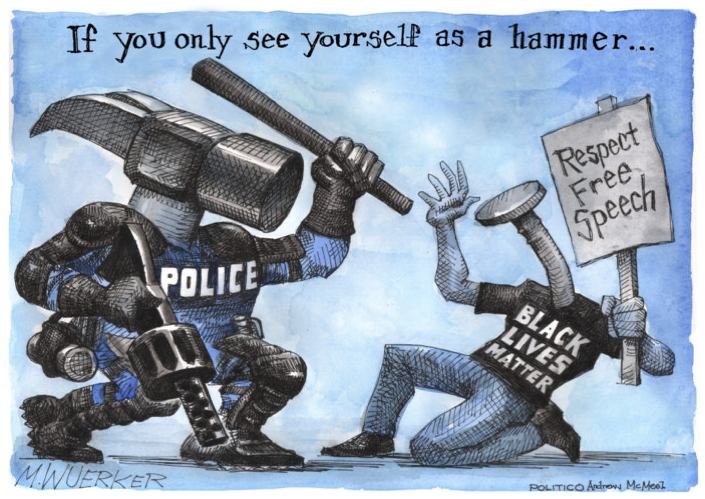

And because the IWW were considered “radicals” and allowed people of color to be members they were suppressed by the authorities, not the least of these being the Los Angeles Police Department and then-Mayor George E. Cryer, whose name is still inscribed on the San Pedro City Hall next to where the unity rally was held.

The rally at Liberty Hill was made infamous worldwide when the LAPD arrested Upton Sinclair, the noted author of The Jungle, while he was reading the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights — the part about freedom of assembly and free speech. He was incarcerated for many days and moved from jail to jail so his bail could not be posted but the hypocrisy was not lost on the public nor the media at the time. He was arrested and charged with “criminal syndicalism,” or agitating to overthrow the government.

The California Criminal Syndicalism Act was found unconstitutional in 1968.

And yet, one year later in 1924, the San Pedro KKK marched down 12th Street to the Wobbly union hall and ransacked the place, beat up and injured the workers, their families, and children. It is reported that members of the LAPD were members of the Klan.

Now this can be dismissed as happening almost 100 years ago and that San Pedro as well as the entire nation has moved on, but the legacy of the IWW and the KKK are like two pieces of the same puzzle that remain like opposing Civil War monuments. The ghosts of systemic racism are still with us today. This is a piece of history rarely taught in schools about class struggle, workers’ rights and racism, even though this is a solidly working-class community.

This town struggles as most of the older Los Angeles areas do with their own identities, attempting to “reinvent” itself at least every 20 years if not daily. It is a kind of attempted amnesia that is constantly believing that the past is dead and that there is only a better future. Perhaps this is driven by our media attention to the silver screen and celebrity inventions. Or maybe we still hold on to some form of manifest destiny, but with no further place west to go, I’m not ever really sure.

What I can tell you is that once about every 27 years we have to go back and relive, re-experience the racism of our past that keeps seeping into our present, exploding onto our streets, on the TV and the news. And people are shocked, shocked that this is happening here in the City of Glass that is so perfectly imperfect. A culture that is more enthralled by the lifestyles of the rich and famous than it is by the value of essential workers. The San Pedro Bay community is just one of the 30 satellite towns in the shadow of this great metropolis. We only get small uprisings here and very little broken glass. Yet, our civic leaders aspire to create the very inequalities that have produced this and previous uprisings, with the kind of gentrification that only exacerbates inequality.

(James Preston Allen is the founding publisher of Random Lengths News. He has been involved in the Los Angeles Harbor Area community for more than 40 years.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.