CommentsVOICES--Not many people noticed when, in early December, the California Court of Appeals reversed a ruling by a lower court in the case Beachwood Canyon Neighborhood Association [BCNA] vs. the City of Los Angeles.

This is not a case that’s going to reverberate through the annals of jurisprudence, but it is important because of what it says about the way the City of LA does business.

Petitioners BCNA filed a complaint after Hollywood residents were denied entrance to a meeting of the Hollywood Design Review Committee (HDRC). The incident occurred in June 2014.The HDRC had been meeting for over two decades, and members of the public had attended for years. These were informal gatherings where developers would present projects proposed for the Hollywood area and stakeholders were able to offer comments. A group of Hollywood residents, including George Abrahams and Doug Haines, showed up at the meeting, just as they had in the past, but were barred from attending.

Why were they barred from the meeting? Aaron Epstein testified that the Councilmember who represents most of Hollywood, Mitch O'Farrell, gave him a clear explanation. According to Epstein, O'Farrell said he didn't want to open HDRC meetings “to people who just want to disagree with me.” Craig Cox said he got a similar justification from O'Farrell, who told him that the HDRC meetings were not open to “people who just want to cause trouble, disagree with projects and file lawsuits.”

The City Attorney's office argued that the HDRC meetings were not open to the public and that Abrahams' and Haines' rights had not been denied, and the lower court agreed, dismissing the suit. But early this month the appeals court reversed that decision. "The petitioners’ allegations and offer of proof were sufficient to show that HDRC meetings were traditionally open to the public, and that a city council member said petitioners were excluded from the meetings because they 'disagreed' with him and had filed lawsuits in the past." The point is that, while government can place some restrictions on free speech, you can't bar someone from participating in a public process just because you don't want to hear what they have to say. (This ruling doesn't end the case. It just allows the lawsuit to go forward.)

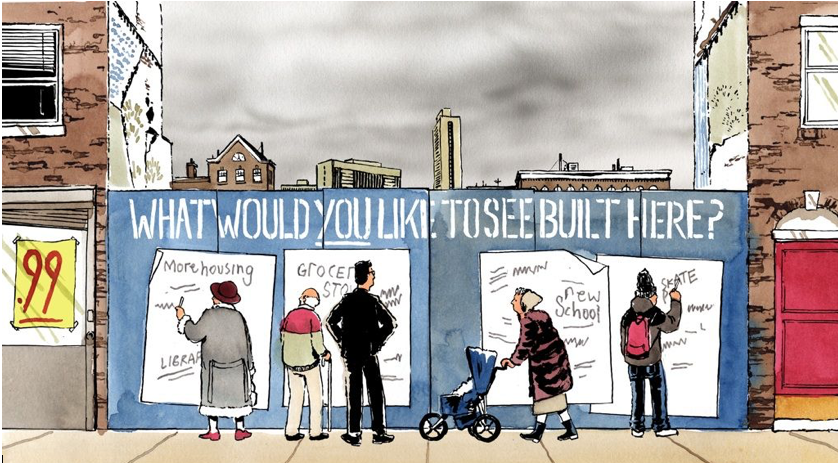

If this were an isolated incident it wouldn't be a big deal. Unfortunately, this is how the City of LA operates much of the time. The doors at City Hall are wide open to developers and their lobbyists, as you can tell by looking at the Ethics Commission web site. It's another story for community activists who are critical of the City's "Build, Baby, Build!" approach. Sure, you can go to public hearings, like those held by the City Planning Commission, where attendees are often allowed a single minute to speak before the CPC votes to approve the project. But getting a chance to offer meaningful input before decisions are made is difficult, in some cases impossible.

Abrahams and Haines do have a reputation for being critical of new development in Hollywood. They have filed lawsuits against the City. Like the one Haines filed in 2011 over a proposed skyscraper at Hollywood and Gower, when the Department of City Planning slid over 200 pages of "supplemental findings" into the case file just before a key hearing, giving the public no time to review the material. Haines took City Hall to court and won. Among other things, the judge wrote that the City had violated the Hollywood community's right to due process.

You want a more recent example? Let's go back to 2018 when Mayor Eric Garcetti unveiled his A Bridge Home program, which was intended to create temporary housing for the homeless. CD 10 Councilmember Herb Wesson jumped in with both feet, unilaterally selecting a parking lot in the heart of Koreatown as a site for one of the shelters, and openly stating he would not hold public hearings to get community input. After weeks of street protests and talk of a recall, Wesson decided to seek community input after all. But Garcetti managed to aggravate the situation further when his office organized a Homeless Solutions Workshop. Flyers circulated on the net billed the workshop as "a convening of community advocates, congregants, lay leaders and clergy to develop a strong foundation for homeless service partnership [....]" Koreatown residents RSVPed for the event, but when they arrived a security officer kept them from entering, showing the group a Post-It note with their names on it. Garcetti later claimed it was an "invite-only" event, but the flyer said nothing about invitations, and in fact encouraged those interested in attending to "Enlist other members of your community or congregation to join you as a team."

To show the lengths that the City has gone to in order to shut the public out of the decision-making process, let's take a look at a case filed in 2015, La Brea-Willoughby Coalition vs. City of Los Angeles. A developer had filed an application to build a project under the City's Small Lot Subdivision Ordinance, and the project was approved. The Coalition filed an appeal with the Area Planning Commission, but it was denied. Why was it denied? Because the Area Planning Commission had failed to hold a hearing on the appeal within 30 days. It gets better. The Coalition then appealed the decision to the LA City Council and was again denied. The reason given this time was that City Planning staff had failed to send the appeal to the Council within 30 days. Was this legal? Incredibly, there was a provision in the LA Municipal Code, Sections 17.06 (A)(4) and (A)(5), that allowed the City to do this. In other words, the City of LA had actually inserted language into the LAMC that allowed them to thwart an appeal simply by ignoring it.

So the La Brea-Willoughby Coalition took the City to court and won. The court declared that the City had violated petitioners' right to due process by denying the appeals to the Area Planning Commission and the City Council without ever having held a hearing. But the Court went even further, stating that Sections 17.06 (A)(4) and (A)(5) of the LAMC were in conflict with State Law, which provides an aggrieved party the opportunity to appeal a tentative map decision to the City Council.

But why did the Coalition have to spend over a year fighting the City in court to resolve this issue? Why didn't the Area Planning Commission simply hold a hearing on their appeal? And how is it possible that the City Council could deny the appeal just because City Planning staff didn't forward it within 30 days?

City Hall will tell you that they do everything they can to invite public participation, holding hearings, forums town hall meetings, and all sorts of other events to give citizens a chance to offer input. The City does schedule plenty of events, but really in most cases it seems like the decisions have already been made by the time the public gets a chance to speak, if they do get to speak at all. One of the best examples of this is City Hall's outrageous lack of transparency in this year's budget process. When the budget was passed in May we were told that the City of LA was doing great, and we could expect an annual surplus of $30 million to $70 million over the next few years. But just six months later, when contracts were approved for City employees, Chief Administrative Officer Rich Lllewelyn warned of annual deficits in the range of $200 million to $400 million. Somehow LA went from a healthy surplus to a crippling deficit in the space of a few months. How is this possible?

It's possible because our elected representatives, who knew full well how the new labor contracts would impact the budget, decided not to share that information with the public. It's possible because there was no meaningful opportunity for citizens to review and comment on the cost of those contracts. It's possible because the folks at City Hall have no real commitment to making sure that the public is involved in public business.

They just don't want to hear from people who might disagree with them.

(Casey Maddren is President of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA), a community group advocating for better planning, and a CityWatch contributor.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.