CommentsLA PROTEST WATCH--A sober New York Times headline last weekend described what many assume has been a dramatic change in fortune for Black Lives Matter, the de facto civil rights movement of the day. “Black Lives Matter Was Gaining Ground,” it read. “Then a Sniper Opened Fire.”

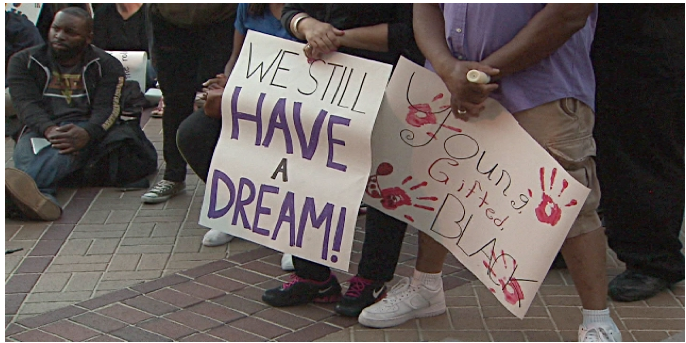

The story outlines how, since 2013, BLM has slowly but steadily built national support for its in-your-face protest tactics and its relentless message that African Americans have borne the brunt of police brutality, often fatally, for far too long. Against the odds, BLM and its larger critique of American racism have gone mainstream and become a de rigueur topic in circles ranging from celebrities to presidential hopefuls. The most recent fatal shootings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile by police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana,and suburban St. Paul, Minnesota, were among the most shocking and egregious of many such killings captured on camera in the last three years, including the high-profile shootings of Michael Brown and Tamir Rice.

These and other images were galvanizing the national conscience, much the same way as images of civil rights protesters being abused by police stunned the public in the ‘60s. But last week, when a black, military-trained sniper killed five Dallas policemen at the tail end of a peaceful BLM protest in that city, this national support allegedly stalled; in its place is a BLM backlash that has emboldened public figures like Rudy Guiliani to declare that by focusing exclusively on black lives, the organization is inherently racist. The question posed by the New York Times and other mainstream media is how, or even whether, BLM will survive.

The criticisms of BLM, especially accusations of racism, are not new. But the Dallas shootings instantly moved such criticism from the background to the fore, giving Guiliani and other pro-police types full license to characterize BLM as counterproductive and even dangerous—one pointed accusation is that in stoking black dissatisfaction, BLM is actually responsible for the deaths of the Dallas cops.

BLM activists have for their part rejected the backlash, as well as the narrative that their cause now hangs in the political balance. National protests against police violence have continued unabated, including in Los Angeles, where the rate of questionable shootings of black people by police is higher than in any other big city. The BLM backlash seems to have actually increased participation in protests.

“Of course people who have power want to say what we’re doing is divisive, but what’s divisive is killing black people,” says Melina Abdullah, a key BLM organizer and professor of Pan African Studies at California State University, Los Angeles. “State-sanctioned violence is the issue.”

Abdullah adds that the group that convened on Sunday at Chuco’s Justice Center in Inglewood for a march numbered in the thousands; typically it would be about 200 people. She says the show of force speaks to the urgency of the cause of police reform and racial justice – an urgency that’s growing, not diminishing.

Akili, a fellow BLM activist and project coordinator for Corporate Accountability International, agrees with Abdullah that the Dallas shootings, tragic as they were, cannot obscure the real, deeply historical problems of inequality that have animated the movement from the beginning. “The two items are separate—the shooting in Dallas, and our demands for justice,” says Akili, who goes by one name. “These two things are not related, but we’re connecting them. That’s wrong. [Sniper] Micah Johnson was a deranged individual and we are not accountable for that. You can’t paint all black people with the same brush, but that happens all the time.” Especially when it comes to acts of violence.

Coincidentally, or appropriately, Los Angeles has become a hotbed of protest this past week. The Sunday night march in Inglewood shut down the 405 Freeway near LAX airport. On Tuesday, protesters were visibly angered by the Los Angeles Police Commission’s ruling that the 2015 fatal shooting of Redel Jones, a 30-year-old black woman who allegedly charged officers with a knife, was in policy. Jones was one of 36 people killed by the Los Angeles Police Department last year. After having swarmed City Hall, only to be refused entry, protesters are now enacting an “occupy” campaign; Abdullah says she and others will stay in the streets until LAPD chief Charlie Beck is fired. They will stay, she says, until that goal is achieved. No more negotiating.

It could very well be a long haul, with long odds for success. Abdullah is undeterred. “It’s summer,” she says. “I’ve got a lot of time on my hands.”

(Erin Aubry Kaplan is a Los Angeles journalist whose posts regularly appear on KCET’s SoCal Focus blog. Her book, Black Talk, Blue Thoughts and Walking the Color Line, is published by University Press of New England. This column was posted most recently at Capital and Main.)

-cw

Explore

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

24

Thu, Apr