CommentsCLIMATE WATCH - Deaths from exposure to emissions from vehicles, smokestacks, and wildfires have increased by more than 50 percent this century, with poorer countries bearing the brunt of the impacts.

Since the turn of the century, global deaths attributable to air pollution have increased by more than half, a development that researchers say underscores the impact of pollution as the “largest existential threat to human and planetary health.”

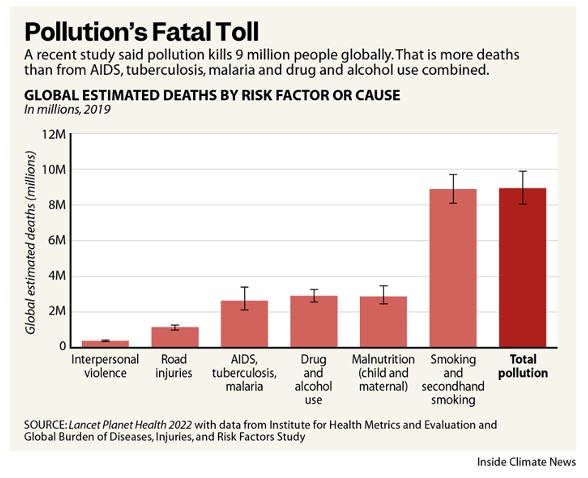

The findings, part of a study published Tuesday in The Lancet Planetary Health, found that pollution was responsible for an estimated 9 million deaths around the world in 2019. Fully half of those fatalities, 4.5 million deaths, were the result of ambient, or outdoor, air pollution, which is typically emitted by vehicles and industrial sources like power plants and factories.

The number of deaths that can be attributed to ambient air pollution has increased by about 55 percent—to 4.5 million from 2.9 million—since the year 2000.

Deaths from ambient air and chemical pollution were so prevalent, the study’s authors said, that they offset a decline in the number of deaths from other pollution sources typically related to conditions of extreme poverty, including indoor air pollution and water pollution.

“Pollution is still the largest existential threat to human and planetary health and jeopardizes the sustainability of modern societies,” said Philip Landrigan, a co-author of the report who directs the Global Public Health Program and Global Pollution Observatory at Boston College.

The report noted that countries with lower collective incomes often bear a disproportionate share of the impacts of pollution deaths, and called on governments, businesses and other entities to abandon fossil fuels and adopt clean energy sources.

“Despite its enormous health, social and economic impacts, pollution prevention is largely overlooked in the international development agenda,” says Richard Fuller, the study’s lead author, who is the founder and CEO of the nonprofit environmental group Pure Earth. “Attention and funding has only minimally increased since 2015, despite well-documented increases in public concern about pollution and its health effects.”

The peer-reviewed study, produced by the 2017 Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health, using data from the 2015 Global Burden of Disease (GBD), found that roughly 1.2 million deaths were attributable to household air pollution (which generally comes from tobacco smoke, household products and appliances); about 1.3 million deaths were attributable to water pollution and 900,000 deaths were attributable to lead pollution.

All told, the study’s authors wrote, roughly 16 percent of deaths around the world are attributable to pollution, which resulted in more than $4 trillion in global economic losses.

Ambient air pollution can be generated by a range of sources, including wildfires.

Deepti Singh, an assistant professor at the School of the Environment at Washington State University, co-authored a separate study into how wildfires, extreme heat and wind patterns can deteriorate air quality.

She noted how in recent years smoke from wildfires in California and the American West has traveled across the United States all the way to the East Coast. At one point during the 2020 wildfire season, Singh said, residents in as much as 70 percent of the Western U.S. experienced negative air quality because of the blazes in the West.

“That wildfire smoke, you know, it has multiple harmful air pollutants,” Singh said. “We don’t even fully understand all the things that are in that smoke. But we know that it’s increasing fine particulate matter, which is something that directly affects our health. It’s something that we can inhale, and it affects our cardiovascular and respiratory systems, and it can cause premature mortality and developmental harm—many, many different health impacts associated with that.”

One of those impacts, Singh said, was increased fatalities from Covid-19 and other respiratory illnesses.

“We’re talking about exposure of people to multiple air pollutants and also exposure of multiple people simultaneously to these air pollutants, which has implications for managing the burden that we’ve put on the health care system,” Singh said.

Michael Brauer, a professor at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, co-authored the study released Tuesday and noted that the 9 million annual deaths attributable to pollution were almost unchanged in the past five years.

“And that’s quite disheartening just given the really staggering impact that this has on health and that this is all preventable, basically,” he said.

“We actually know how to deal with this problem,” Brauer said, referring to the need to adopt clean energy solutions. “And yet we still have this impact.”

He said that he hoped the study would be a “a call to action.”

“Let’s take this seriously and put the resources that need to be put in—both financial resources, but really political willpower—to deal with this and we will have a healthier global population,” he said.

(Victoria St. Martin covers health and environmental justice at Inside Climate News where this story was first published.)