Comments

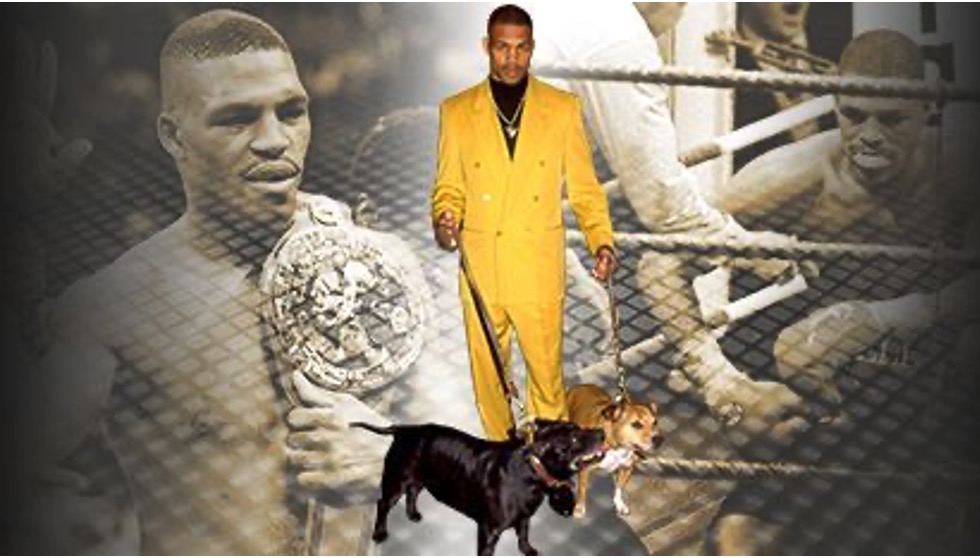

ANIMAL WATCH - Gerald McClellan (aka, the “G-man”) was a powerful professional boxer and two-time middleweight WBO and WBC champion inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in California in 2007 who reached his 56th birthday last week, on October 23, 2023, still suffering from severe brain damage inflicted during his final extremely violent fight lost to WBC super-middleweight champion Nigel Benn in 1995. But McClellan has been rejected by the industry due to his extreme addiction to Pit Bulls, animal cruelty and proven involvement in dog fighting.

McClellan has spent the years helpless and totally cared for by his younger sister, Lisa, and reportedly still suffering from a severe brain injury which left him unable to function and forced him to retire.

There are those who claim McClellan, who was at one time called a “miniature Mike Tyson,” was unjustly cast aside after he was no longer useful. But, there are also those who say that the industry which thrives on human-to-human violence needed to distance itself from a man who openly boasted about his involvement in dog fighting and was running a dog-fighting ring.

Tyson himself, while incarcerated, reportedly had called McClellan “the best fighter in the world,” but his addiction to Pit Bulls and dog fighting caused the boxing industry to turn its back and abandon responsibility for one of its own, and there are also many who say this is well-deserved.

This is an opportunity to look inside this behavior and observe the dangers of addiction to blood sports and violence, which often begins in childhood, and the bloodlust that increases in intensity with adulthood.

THE G-MAN’S HISTORY

The article by Kevin Mitchell in the Guardian, which explores the mind and actions of Gerald McClellan, the dog fighter, is difficult to read but brings brilliant insight and an in-depth opportunity to see into the mind of a man who thrived on the suffering and death of dogs in fighting matches.

Gerald McClellan was tragically injured in his last match against Nigel Benn that ended his career in 1995. He enjoyed the violence.

Highlights of the Benn vs. McClellan Fight

Benn vs McClellan (below are excerpts, with a link to the report of the entire fight.)

Main article: Nigel Benn vs. Gerald McClellan

In February 1995, going into the fight McClellan had won his last 21 fights—the last 14 of those by knockout; with 13 of those knockouts in the first three Rounds. McClellan had never been beyond Round 8 in any of his previous fights, insisting that he rarely needed more than three rounds to defeat his opponents.

McClellan was severely injured as a result of the contest. After collapsing in his corner post-fight, McClellan was rushed to hospital where a blood clot was discovered on his brain. To this day, McClellan has short-term memory problems, is almost completely blind, partially deaf, and uses a wheelchair. Although he has regained some movement and some of his hearing since 1995, having been 80% deaf and he can now walk with a cane, according to reports.

WHEN DID GERALD MC CLELLAN LOSE HIS MORAL COMPASS?

In dog fighting—as in boxing and many other legitimate sports—the thrill of danger, imminent death, and gambling can overpower normal sensibility and mask the line of acceptable conduct and, as in the case of Gerald McClellan, the line can become so blurred that inflicting pain on another living being can bring overwhelming gratification This is an essential trait for a successful boxer, but it must stop at the ropes.

Proven Involvement in Dog Fighting, Removed All Sympathy

A 2001 report by ESPN, reveals the details of an investigation that showed Gerald McClellan had more than just a cursory interest in dog fighting; and, in fact, was maintaining (like Michael Vick) a kennel operation to breed, train and fight dogs, which destroyed any sympathy that might have been felt by many who felt concern about the disturbing end of his boxing career, and his injuries.

The report states, that in 2001, police raided the former boxer’s property in Texas after receiving credible tips linking him to an organized dog-fighting ring being run out of the premises. The investigation confirmed that “McClellan was heavily involved in breeding, training, and conditioning Pitbull terriers specifically for violent confrontation with other dogs. On his property, authorities discovered cages housing muscular dogs exhibiting battle scars, as well as equipment used to train dogs for maximum aggression in combat.” It also discusses “meticulous,” detailed records kept by McClellan, documenting previous fights he had arranged on his property as gambling events.

In Fighting for life, posted on November 4, 2001, sports reporter Kevin Mitchell reviewed an earlier interview at the G-Man’s Las Vegas rematch with Julian Jackson, In Las Vegas in 1994, which revealed that Gerald McClellan was on a course of violent behavior that he could not control. He was addicted to sex, according to reports, but seemingly even more addicted to watching dogs fight.

Mitchell wrote that “Nigel Benn's 1995 world title victory over Gerald McClellan ‘brought all the contradictions of boxing together in one moment of clarity. It was beautiful and ugly, thrilling and frightening. And in the decisive round, those who saw it knew the intensity had gone too far.’”

Gerald McClellan was a bad man (contains graphic descriptions)

Kevin Mitchell

Sunday November 4, 2001

Observer Sport Monthly

In Las Vegas in 1994, when Gerald McClellan was preparing for his rematch with Julian Jackson, the one-eyed hitter he’d stopped the year before to win his world middleweight title, he was in his hotel room. He was bored, anxious. He got a video out and slipped it in the machine. The fight was only a few hours away. It was the biggest of his career. There was nobody about and the world champion settled down to get his kicks.

As the tape rolled, Stan Johnson, McClellan’s coach, knocked on the door.

‘He's some guy,’ Stan recalls. ‘I think he'd be in his room before a fight, getting’ a little ***** or somethin’ before he go to the fight ... well, Gerald be in the room this time watchin’ tapes of dog fights. I thought he be watchin’ a sex movie. But I goes into the ****in’ room, Gerald’s got a tape of himself watching the dogs with a stockin’ over his head where you can’t see who he is – in case somebody find the tape no one know it’s him!’

This is how Stan saw Gerald and the whole dog thing: ‘So he got this black Labrador, just went to the dog shop, told the man, “I need a dog to take care of, I'll take this Labrador home,” and the man say to the dog, “Yeah, you got a good home now,” and Gerald takes the dog home. He takes the dog down his basement and tapes the Labrador’s mouth, takes his pit bull Deuce and says “Get him!” He lets Deuce start eatin’ the dog up while he’s timing it on a watch, see how long it would take his dog to kill this dog.

And I said to Gerald, “Hey, Gerald, this Labrador wouldn’t beat Deuce, no way, so why did you tape his mouth shut?” ... And he said, “Just like a fighter need to spar every day, he don’t need nobody bustin’ him up when he got a big fight comin’ up. He just need to bust somethin’ up hisself. Right?’”

It was impossible not to be mesmerized by the rhythm of the telling, and by the tale itself. It was a kind of rapping, old-style ghetto cool-speak, all mixed up like a cheap stew, bits of profanity chucked in to pepper it up. Comfort language served up by a badass dude.

Gerald got his comfort between the sheets. Any time of the day or night. ... But Gerald had a dark side to him, because he was a violent, violent, violent, violent, violent person. I had to check: that was five ‘violents’. Stan was just making sure.

‘His whole life was about fightin’ and all, pit bull dogs, he pay lotsa money on dog fights, he took money from his fights and he bet. It weren’t nothin’ him go down the projects in Chicago and bet $10,000 his dog beat your dog. And a bunch o’ gang bangers with guns and drugs all come down to watch....’

Donnie Penelton, the Black Battle Cat, he remembers the dogs. He was there too on those dark nights.

Yeah, Gerald’s my first cousin. We grew up together. I’m older than him, and from the age about three, four, he hangin’ around buggin’ me from about then, yeah. He was a nice, young scary kid. He was a maniac with the pit bull dogs, man. He was like one hisself. Very aggressive. Very crazy. He had like a yard full of pit bulls. We’d mostly take ‘em to Detroit with us, to the camps.

He brought Deuce down to fight this guy’s dog in Chicago one time, and me and Donnie, we went down there with him ... Gerald was drivin’ his Mercedes Benz, a green car with caramel-coloured seats and he had this big, beautiful truck behind where he carried his dogs in cages. So Deuce, he winnin’ this particular fight and all of a sudden the dog got on him and he started rippin’ Deuce's throat out. So I'm kinda, like, lookin’ at Gerald and I was seein’ the ‘spressions on his face, you know, and just as his dog was gettin’ beat, Gerald told the dude, “Stop the fight!” And the dude said, “No, man. No, man, you started the fight.” And Gerald says, “You stop this mother****in’ fight! Stop the fight! I quit, here your money.”

Gerald had a nice green leather suit on, he picked his bloody dog up, threw his dog across his shoulder, blood run all down his ****in’ coat. Instead o’ puttin’ him in the truck, in the cage, he put him in the back seat o’ the Benz, mad as hell, rubbing his dog, cryin’ up and down the road, tellin’, “I ain’t never gonna do this **** no more, I don’t know why I did this, I keep a mess o’ snakes afore I put a dog through this again.” You know?

I knew before I started that some of this story wasn’t going to make easy listening, but this kind of information was confusing. It was not just hard-core boxing stuff; it was the sound of streets I didn’t really know. But Gerald and Stan felt at home there. So did Tyson. Listen to Iron Mike’s angrier outbursts: he is shouting at the largely white world and he is saying, I’m going home to the streets and you can’t come.

MCCLELLAN ALSO CRUEL TO OTHER ANIMALS

In his original column in 2001, Kevin Mitchell posted the G-Man’s comments as he heard them. “I could only wonder what else they got up to. Stan, unsurprisingly, had a million stories,” Mitchell wrote.

‘We in Florida one time,’ he says, ‘we in trainin’, just before we go to fight Nigel Benn. Gerald says, “You wanna go to the mall to do some shoppin’?” So we go to the mall with the champ to do some shoppin’, and we come outta the mall, and in Florida you got these pretty little pelican birds, what you call ‘em? Flamingos, that’s it. They just walk around the mall tryin’ to make it look pretty. But Gerald comes out, and says, “Right, watch this, watch this!” And there’s this flamingo walkin’ around on the road. Gerald gets close and makes a dip with the car, he speeds the car up real bad and – boom! – he hits the damn flamingo! And the flamingo flies up all over the grille!

And Gerald, he’s laughin’, like it’s all in Disneyland, and he goes flyin’ round the block and he looks at the grille and he looks at the bird feathers and he pulls the bird feathers and pulls the bird outta the grille, and, it’s like, “Damn! Did you all see that? Did you all like that?” And then he was on his way out – and you know, you can go to jail for doin’ that sort of shit, you know? That's a state bird! You know what I mean?”

“I know what you mean, Stan,” Kevin Mitchell responded.

So then Gerald goes around again! He already run over a couple of pelicans and then here come another pelican and you know, like, this mother**kin’ pelican must be wonderin’ what’s goin’’ on here, like? He must be like a brother or sister, like, they all busted up. And then Gerald, he says, “Look at this nosy sonofab**ch, watch this.” And – bam! - he rammed over that one. I said, “Gerry, you gotta stop this, man, we gonna go to jail.” And he tried to make it look like it’s an accident, that the bird was there, like ... The kid was a violent kid. He loved killin’ sh*t, he loved dog fights, like it was evident, he was want to go out like he went out...

“Like Deuce. Except he made Deuce quit.”

These words also vividly describe the morbid saddism behind thousands of dog-fight enthusiasts’ obsession with watching two dogs tearing at each other’s faces, throats and bodies. Some dogmen mercifully stop the fight; when their dog “turns”—meaning it does not want to or cannot fight any longer. Others blame the dog for its weakness and failure and enjoy watching it suffer for its betrayal.

McClellan did stop one fight when his dog, Deuce, was losing badly, according to numerous reports by friends and his own admission.

Mitchell writes, “Watching animals fight was one of the first recreational events of primitive civilizations, which merely capitalized on the innate nature of males for survival-of-the-fittest for mating and assuring the strengthening and endurance of animals which provided food for humans.”

“But, today, organized sports are available to fulfill the need to ‘win.’ And both genders have the right to selection of a mate. However, it seems a large segment of humanity may have evolved physically, but not emotionally, above the need to prove dominance by pitting two animals which would not otherwise fight and agitating them to the point of conflict, for the purpose of wagering on the outcome—rather than risk embarrassing themselves by personal performance.”

He describes the decisive round of the McClellan-Benn fight vividly, stating “those who saw it knew the intensity had gone too far.” This is the real story of the night that left a fearsome fighter irreparably brain-damaged.”

WAS MCCLELLAN’S LOSS KARMA?

Unlike the forgiveness granted to Michael Vick (largely due to publicity when Best Friends Animal Society which received $389,000 from the court to take 22 of his dogs to “rehabilitate,”) according to the New York Times, McClellan’s public violence and blatant cruelty toward animals, including his own Pit Bulls, when disclosed, overshadowed his powerful athletic skills in the ring thus there was no forgiveness for him after his loss.

The G-man was an anomaly, even in a profession characteristically driven by violence, and he met a fate in the ring himself that resulted in a life of helplessness that could be considered Karma—except that there is no evidence that he was lucid enough to remember his final moments in the ring.

Reportedly he asked a number of times if he had “lost.” That question was posed to his manager, who responded, “Gerald quit, man. He quit like a dog.”

(Phyllis M. Daugherty is a former Los Angeles City employee, an animal activist and a contributor to CityWatch.)