Comments

PERSPECTIVE - In January 1962 a graduate student in anthropology at Catholic University, Eliot Liebow, signed on as a field researcher for a study set in a low income, African American neighborhood in Washington DC. Utilizing a technique he had learned of “participant observation,” Liebow went regularly for the next 18 months to a Carry-out shop on the corner of 11th and M, where he embedded himself in the lives of the neighborhood men who gathered at the shop. He befriended them, joined them for social events, followed their experiences in and out of jobs, and visited them when they were in jail.

In 1967, Little Brown published his field notes as a book, Tally’s Corner: A Study of Negro Streetcorner Men. Within a short time, the book would become a social science publishing phenomenon. It would go on to sell over one million copies, be reprinted multiple times (including a 2003 edition with an introduction by William Julius Wilson), and be widely adopted in college and university classes. Its core narrative about low income men, a dysfunctional subculture, and the power of a job to change this subculture, would help give rise to a burgeoning workforce system.

In 2025, the unemployment of low income men (of all races) is at the top of the policy agenda of foundations, think tanks, and workforce groups—and a main topic of the Philadelphia Federal Reserve’s “Economic Mobility Summit” this month. As has been widely noted, the labor force participation rate of all working age men, 25-54, has been declining since the 1960s, with the decline most pronounced among lower income men without postsecondary education.

Tally’s Corner today provides a valuable long term perspective on low income men outside the job world. Its narrative, the power of a job in altering behaviors, has been validated in good part by workforce programs over the past six decades. But as industry structures rapidly change, the narrative is incomplete, and requires additional elements going forward.

The Men of Tally’s Corner: 1962

Let’s start with revisiting Tally’s Corner.

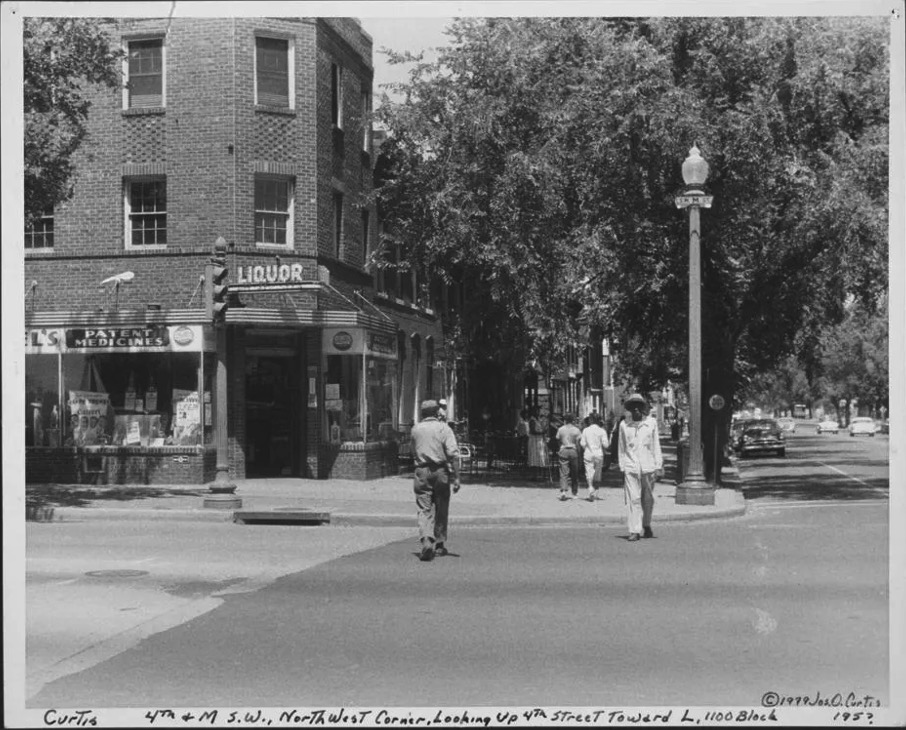

“The New Deal Carry-out shop is on a corner in downtown Washington D.C. It would be within walking distance of the White House, the Smithsonian Institution, and other major public buildings over the nation’s capital, if anyone cared to walk there but no one ever does, Across the street from the Carry-out is a liquor store, The other two corners of the intersection are occupied by a dry cleaning and shoe repair store and a wholesale plumbing supplies storeroom and warehouse.”

When he first arrives at the Carry-out in early 1962, Liebow meets Tally, 31 years of age, who is one of the regulars. Through Tally, Liebow comes to meet some 20 other neighborhood men who frequent the shop from time to time, coming to “eat and drink, to enjoy easy talk, to learn what has been going on, to horse around, to look at women and banter with them, to see ‘what’s happening’ and to pass the time.”

Liebow writes with a novelist’s eye for detail and dialogue. He enjoys the camaraderie he is able to develop with Tally and some of the other men (Sea Cat, Richard, Leroy). He appreciates the willingness of the men to open their lives to him.

At the same time, he does not present the men as heroes or generally worthy of emulation. Rather, his descriptions emphasize the disorganization and dysfunction that characterize relations that the men have with women, with children they have fathered, with other men in the neighborhood, and with employers.

With rare exception the men are portrayed as exploiters of women in their lives, unfaithful in marriages, in and out of relationships, drawing on women financially. They neglect children they have fathered. Disputes with other men in the neighborhood can erupt in violence at any time.

The men have some paid work, but the work is often intermittent as well as low paid. Tally works as a semi-skilled construction laborer for six or seven months a year; Richard in janitorial jobs, Leroy as a parking lot attendant, The other men have sometime jobs as laborers, countermen, stock clerks, dishwashers and delivery drivers.

For the men, though, work generally is a low priority. Liebow explains:

“Putting aside for the moment what the men say and feel and looking at what they actually do and the choices they make, getting a job, keeping a job, and doing well at it is clearly of low priority. Arthur will not take a job at all. Leroy is supposed to be on his job at 4:00 pm but it is already 4:10 and he still cannot bring himself to leave the free games he has accumulated on the pinball machine in the Carry out. Tonk started a construction job on Wednesday, worked Thursday and Friday, and then didn’t go back again. On the same kind of job, Sea Cat quit in the second week., Sweets had been working three months as a busboy in a restaurant, then quit without notice, not sure himself why he did so.”

Most of the book is an ethnography of the men’s behaviors (with chapters structured by relations, “Husbands and Wives’, “Lovers and Exploiters”, “Fathers without Children”, “Men and Jobs”). In a concluding chapter, though, Liebow seeks to tie together these behaviors to a common cause: the inability of the men to earn enough to support a family, the inability to be “the man of the house”, to assume the provider role he knows he should play.

“The way in which the man makes a living and the kind of living he makes have important consequences for how the man sees himself and is seen by others; and these, in turn, importantly shape his relationships with family members, lovers, friends and neighbors.”

To Liebow, the integration of the men into the social and economic mainstream can only come through jobs that are steady and pay a decent wage. Though Liebow does present a dysfunctional streetcorner subculture, he argues that this subculture will change as there are changes in the employment status of the men. The book ends with a call for a new jobs strategy aimed at low income men—though Liebow is vague on the what forms this strategy should take.

The Power of The Job

Liebow spent his career after the publication of Tally’s Corner mainly as a researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health, where he rose to chief of the Center for the Study of Work and Mental Health. He wrote one additional book, a profile of women in homeless shelters in Washington DC, published in 1993. He passed away in 1994 from cancer. According to his widow, Harriet, he kept in touch with the men of Tally’s Corner, but never wrote about them again.

Tally’s Corner and other influential books of the 1960s on low income men and jobs (The Other America, Employing the Unemployed ) would help give rise to a greatly expanded publicly funded workforce system. Federal workforce funds would skyrocket from $450 million in 1964 to $2.6 billion in 1970.

In the early years, the War on Poverty workforce and community action programs squandered much of the money, spending with little or no accountability, and no required outcomes (novelist Tom Wolfe would capture the folly of these programs in his 1970 essay, “Mau-Mauing the Flack Catchers.”). But by the late 1970s, a reset was in place, with clearer metrics in terms of placements, a closer tracking of spending, stronger links with real employers. Since the 1980s, the workforce system has continued to improve: sharpening employer connections and sector strategies, widening workplace learning and apprenticeships, expanding retention structures.

The system since has borne out Liebow’s ideas on the power of a job. Various individual and group counseling therapies would be put forward over the years to bring the men of Tally’s Corner into the social and economic mainstream. None would yield the positive behavioral impacts that would come with placement and retention in a job. Such placement was often accompanied by on-going counseling and supports. But it was the job, not the counseling and supports, that was the main driver in helping low income men find a confidence, structure and organization in their lives, as well as economic gains.

Job opportunities and even job placements did not succeed with a significant segment of the men, who dropped out of job programs or jobs after a short time. Mental health conditions, cognitive gaps and developmental disabilities, personal and lifestyle values downplaying steady work, all undermined job success. But any job strategies need to take these factors into account, and recognize the limitations of even the best-designed programs. And sometimes those who drop out, come back as they mature or find themselves ready to take advantage of opportunities—a point made often by the longtime workforce practitioner John Colborn.

Low Income Men and Jobs Today

Revisiting Tally’s Corner and the workforce system it helped spur are starting points for thinking about employment strategies today.

Despite the positive impacts of workforce programs, these impacts have been overwhelmed by other economic and social forces over the past six decades impacting and impacted by low income men. These forces have been oft-noted in the media and academic literature: the shifts in industry structure, particularly manufacturing; the widening eligibility and growth of benefit programs, especially SSI and SSDI; declining marriage rates, substance abuse disorders and levels of incarceration. They have brought us to the current state in which the progeny of the men of Tally’s Corner are more numerous than ever.

The current workforce system for these men, its customized training and placement services, represents a foundation on which to build in the next years. Yet, a broader rethinking of the system is in order, reflecting industry shifts and the rebound of the blue collar economy, the role of wage mobility, advances in the behavioral sciences and neurosciences, and lessons from the successes of welfare reform. Among the questions to be asked, as part of this rethinking:

Can work requirements for low income men succeed in ways that welfare reform has succeeded for low income women? Welfare reform changed the culture of welfare offices into employment hubs, and achieved many successes in identifying the strengths of low income unemployed women and assisting them into new confidence and jobs. Can the same be done for low income men who are on various forms of public assistance?

Can the workforce system more fully take advantage of the rebound in America’s blue collar/practical economy? As Gad Levanon, chief economist at Burning Glass Institute, notes in a post this past week regarding blue collar/practical economy occupations, demand for workers in these occupations is growing, even as demand for workers in tech, finance and other white collar jobs declines. Can the workforce system more fully take advantage of this shift through apprenticeships, career technical education?

Can the workforce system capture the advances in the behavioral sciences and neurosciences? Over the years, the system has tried various counseling and therapies to address behaviors by low income men that undermine job success. Outcomes have been modest. But science’s understanding of the brain is at an early stage. Going forward advances in brain science may help shape more effective interventions, relevant to the workforce system.

Can the workforce system build better mobility structures? Mobility for low wage entry level workers is a goal that has befuddled workforce practitioners for decades. Yet it is in such mobility that may be found improved labor force stability for low income men, as well as movement into the family-supporting jobs that Liebow envisioned.

The men of Tally’s Corner today are facing a more complex and challenging job world than the job world of the 1960s. The workforce system will need to adapt, even as it keeps sight of the first principles of jobs and behaviors.

(Michael Bernick served as Director of the state labor department, the Employment Development Department, following eight years as a Board member of the BART transit system. He currently is an employment counsel with the international law firm of Duane Morris LLP, Milken Institute Fellow and Fellow with Burning Glass Institute. His newest book is The Autism Full Employment Act.”)