Comments

BROWN AMERICA - “Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color…” opens Maggie Nelson’s book, Bluets, a study devoted to the hue that spurred a Picasso period, the blues of the Deep South, and Yves Klein, the artist who even turned urine blue.

I, too, have fallen in love with a color—it was a bit obsessive. For me, Brown has always been everywhere, is everywhere. But to truly love it, I had to learn to see it anew, to meet it again and again in various forms, own it, and honor it. Only then, in Brown, I found a place to define myself and grow.

What is Brown? We brown-nose, we bake brownies, we live in brownstones, we have brownouts, and to quiet the clamor we listen to brown noise.

For me, Brown was first Queens, New York, aka the World’s Borough. Home to 130 different spoken languages—Spanish, Russian, Korean, Greek, Urdu, and Tagalog, to list just a few—my hometown represents over 120 countries. On 107-17 64th Road, 11375, Brown was everywhere, so like the fish in the sea that doesn’t know water from air, I didn’t know how special it was.

Still I remember being a kid faced with the dilemma of coloring myself on a blank sheet of paper, and I couldn’t color myself in: “None of these colors look like me.” I mean, of course, if I wanted to, I could use the peach crayon indicated for “flesh”—but whose flesh? So instead I opted to make myself green and purple and orange. Like when you go out to get a Band-Aid and it doesn’t match your skin—so you go with the colorful ones, with cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny or the Flintstones on them.

Brown exploded into my life in 2018. I was living in Los Angeles, doing the Hollywood thing, and one night I was invited to see Ta-Nehisi Coates—a person many have called our modern-day James Baldwin—speak at the public library in downtown Los Angeles. I’d never heard of him before. But my friend insisted he was a big deal.

Coates spoke about Black and white, and then he spoke some more about Black and white. Everybody was filled with awe, and the occasional “Yes, yes, brother.” And it was well-earned; it was intellectual church.

When it came time for questions, I hesitated. I really didn’t want to say anything, because at the time, I wasn’t a raise-your-hand kind of person. I didn’t trust I had anything of value to say. But I knew I needed to ask him a question now or I would regret it forever. So, I asked: “Black and white, that’s all I hear, Black and white. As a Brown man, a Dominican, Colombian, Latino in this world, where does that leave me in the conversation?”

Coates took a short breath and responded, “Not in it.”

“Not in it?” I asked.

“Not in it,” he replied.

The moderator snatched back my microphone. They moved on to the next question, and I sat down like a child reprimanded for asking a stupid question with a simple and obvious answer.

On 107-17 64th Road, 11375, Brown was everywhere, so like the fish in the sea that doesn’t know water from air, I didn’t know how special it was.

I was dumbfounded. I wasn’t in this conversation? What a curse to be told you do not exist in such a vital conversation in America, I thought.

And so my obsessive journey with Brown began. I was a baby learning to walk again, tripping and falling all the way across the room.

After the talk, I was supposed to go to dinner with some friends, but too keyed up, I went home instead. I stared up at the ceiling of my small, Little Armenia studio, wondering: “Not in it? Why am I not in it? Where am I? Where are the Brown bodies? Where are our stories and our voices? Where are my father and mother? Where are the people I love?”

These questions began to consume every inch of my life.

For a while after, I could no longer do anything without the weight of race in it, without seeing or hearing this not-in-it-ness. It was exhausting, I couldn’t watch a movie, or go to the park with all the joggers and dog owners, or read the news, or get a cup of coffee, or go on a date. Even a haircut paralyzed me. If I cut the curls off, am I losing my identity? If I go traditional crew-cut, will that make me more ethnically ambiguous, and is that what is wanted of me by Hollywood, by media, by culture? Will that push me closer to some sort of “success”? To cut or not to cut?

Then, some six months later, I saw a solo performance by the Salvadoran American playwright Brian Quijada. It was called Where Did We Sit on the Bus? Brian tells the story of a question he once asked a teacher when his class was learning about Rosa Parks during a Black History Month lesson. Looking around his public school room, he saw white kids and Black kids and wondered, first to himself, and then, out loud to the teacher: “What about Brown Hispanic people? Where were ‘we’ when all of this was going on? Where did we sit on the bus?” The teacher told him, “You weren’t there.”

This got at exactly what I’d been feeling—it’s impossible that we weren’t there. On August 28, 1963, when MLK led the march on Washington, out of the 200,000 to 300,000 people who attended, thousands were Latinos—many of them Puerto Ricans from NYC. This is largely because MLK asked Gilberto Gerena Valentín, then president of the Puerto Rican Day Parade, to get the Latino population to turn out. For King, having a Latino presence was necessary. He said to the masses, “There is discrimination not only against Blacks, but also against Puerto Ricans and Hispanics.”

We were there when there were white water fountains and Black water fountains, white bathrooms, and Black bathrooms. We, Latinos, Native, Indigenous, Mixed, Middle Eastern, Asians, and other underrepresented communities were there, facing our own discrimination, somewhere in the middle of Black and white.

America is becoming Browner every day. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in about 25 years, the nation’s population will become “majority-minority.”

Each and every one of us wants to be a part of something. We want to walk into a room and know: I belong here. But there isn’t a sense of cohesive Brown identity.

Being in this middle, fluid space can feel at times like there is no separation between up and down, right and wrong, fail and pass, this and that, his and her.

Because it is such a wide category, so vast, for a time, my own individuality, my own specificity, my own “Christopher Rivas-ness” felt lost.

But since I have become obsessed with Brown, and have started to see it for what it truly is, now I embrace the millions of complex shades it holds. Because to say, “I am Brown,” is to say, in this Black / white world, I am somewhere in the middle—a space beyond dualistic and binary thinking. There are no fixed endpoints. Nothing is ever set in stone. In Brownness we are always becoming.

Looking back to that night in 2018 when I was told I existed outside of the Black/white conversation of race in America, I still feel like Coates wasn’t wrong: there is still a very clear line in the sand, a clear divide in our binary world between Black/white. Though that conversation was shocking and hurtful, it helped me engage with the alchemic power and privilege of my Brownness, and how to best use my privilege of being able to navigate the middle and sometimes play both sides.

Now, when I think about Brown, I think about it as both color and concept. It is the color of roots. So many pigments of Brown come from and indicate dirt—from which everything grows; our sustenance, the trees that give us the air we breathe.

I can now celebrate my cultural, ethnic, and racial identity and bring to light some of the issues and problems we face. In short, I can now put myself in it and carry my Brownness proudly.

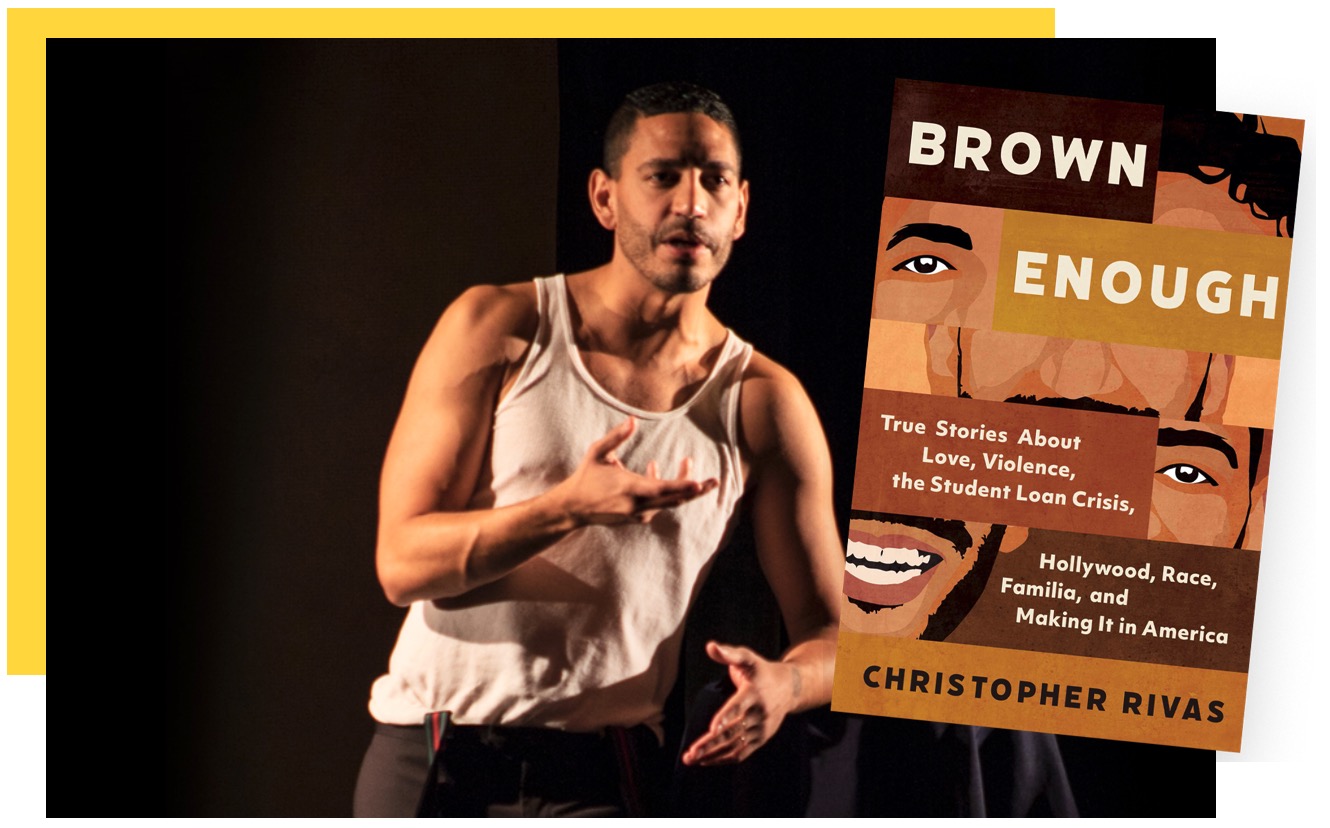

Christopher Rivas is a storyteller, actor, and author of Brown Enough: True Stories About Love, Violence, the Student Loan Crisis, Hollywood, Race, Familia, and Making It in America. This article was first featured in ZocaloPublicSquare.org.)