CommentsGUEST COMMENTARY - There was no leader in the twentieth century who did more to end the Cold War, the over-militarization of his country, and the reliance on nuclear weaponry than Mikhail S. Gorbachev.

At home, there was no leader in a thousand years of Russian history who did more to try to change the national character and stultifying ideology of Russia, and to create a genuine civil society based on openness and political participation than Mikhail S. Gorbachev. Two American presidents, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, could have done much more to help Gorbachev in these fateful tasks, but they were too busy pocketing the compromises that Gorbachev was willing to make.

Gorbachev’s decisions in a short six-year period from 1985 to 1991 were responsible for the decline in the Soviet military presence in every major region in the world, and the reduction of Soviet military aid and advisers in every key Soviet client state. He worked closely with the United States to resolve crises in Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Nicaragua, and even the Persian Gulf. Gorbachev changed Soviet policies and behavior at home and abroad, and—like Talleyrand in the case of France—understood that Russia could not be great if it was merely powerful.” The United States is still waiting for a leader who understood Talleyrand—and Mikhail Gorbachev.

The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan.

On the first anniversary of America’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan, it is important to remember that Gorbachev’s initial decisions in national security policy involved the withdrawal from Afghanistan that even left behind a government that had functioned for several years. As early as April 1985, only one month after he took power, Gorbachev requested a “hard and impartial analysis” of the Afghan situation in an effort to “seek a way out.”

The United States was not willing to help. Although U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz was prepared to provide assistance to the new Afghan government that the Kremlin left behind, he was opposed by Reagan’s national security team led by General Brent Scowcroft and Robert Gates. As Gorbachev said to Shultz, the Soviet Union wanted to leave Afghanistan, but the United States kept putting “sticks in the spokes.”

The Soviet Withdrawal from Germany.

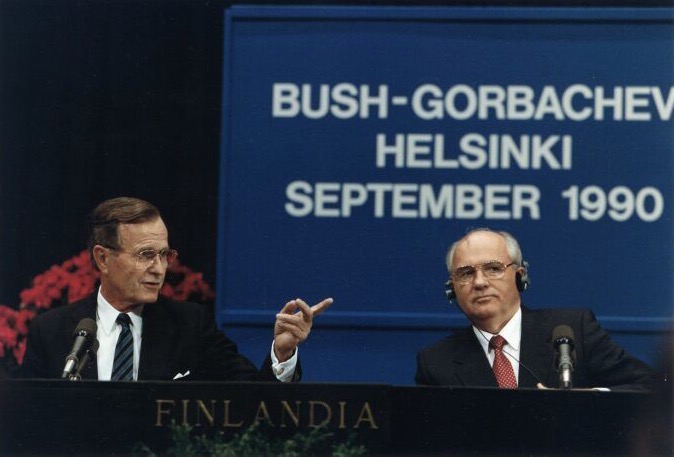

One of Gorbachev’s most fateful decisions was the Soviet military withdrawal from East Germany in 1990 and the acceptance of a reunified Germany in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). He is vilified in Russia to this day for these decisions. One of President Bill Clinton’s most fateful decisions was to orchestrate the expansion of NATO in the 1990s, which repudiated Secretary of State James Baker’s commitment to Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze that the United States would not “leap frog” over Germany to position itself in East Europe if Gorbachev withdrew Soviet forces. Baker was even willing to put this verbal commitment in writing, but he was overruled by Bush’s national security team. Again it was Scowcroft and Gates.

Gates’ opposition to Gorbachev was so well-known that when he met Vladimir Kryuchkov, his KGB counterpart, for the first time, the latter said “I understand that the White House has a special cell assigned the task of discrediting Gorbachev. And I’ve heard that you are in charge, Mr. Gates.” Both secretaries of state Shultz and Baker had to intervene with Reagan and Bush, respectively, to stop Gates from undermining U.S. policy toward Moscow. Shultz confronted Gates in 1987 and reminded the acting CIA director that he was “usually wrong” about Moscow and that he had dismissed Gorbachev’s policies as “just another attempt to deceive us.” Gates himself often bragged that he was the only CIA director in history who a Soviet president and two secretaries of state wanted to fire.

The Iraqi Withdrawal from Kuwait.

Gorbachev was responsible for the unprecedented cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the 1990-1991 crisis in the Persian Gulf, the first test of the post-Cold War era. Gorbachev had to overcome strong domestic opposition to do so, and even General Scowcroft conceded that it would have been a “very difficult history” for the United States in the Gulf without Moscow’s support. Presumably Saddam Hussein believed he could count on Soviet support for his aggression against Kuwait in 1990, but that was not the case.

Gorbachev’s Centrality to Arms Control and Disarmament.

The rich history for arms control and disarmament between 1985 and 1991 could not have been possible without the central role of Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev’s concessions in the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty were responsible for the elimination of an entire class of nuclear weapons and the lessening of Cold War atmospherics throughout East and West Europe. Gorbachev’s concessions in the reduction of forces throughout East and Central Europe were central to the eventual conclusion of the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty in 1990. Moscow’s unilateral reductions in East Europe in the late 1980s paved the way for the CFE Treaty.

I resigned from the CIA in 1990 primarily because of the agency’s misreading of Gorbachev that was dictated by CIA director William Casey and his leading deputy, Bob Gates. Their politicization of the intelligence meant that the CIA and the White House could not anticipate any of the major events associated with Gorbachev’s leadership, including the withdrawal from Afghanistan; the retreat from the Third World; the unwillingness to intervene in the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the sudden acceptance of Germany’s reunification a year later.

Whereas Gorbachev understood the economic and social decline of the Soviet Union, telling his wife Raisa that “We can’t go on living like this,” the CIA was still telling President Reagan that the growth rate of personal consumption actually exceeded that of the United States. Reagan used CIA’s phony intelligence on the Soviet economy to justify the largest peacetime increase in U.S. defense spending in history. Gorbachev was a heretic in the Kremlin; unfortunately, he was not sufficiently appreciated in the halls of power in Washington.

(Melvin A. Goodman is a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy and a professor of government at Johns Hopkins University. A former CIA analyst, Goodman is the author of Failure of Intelligence: The Decline and Fall of the CIA and National Insecurity: The Cost of American Militarism. and A Whistleblower at the CIA. His most recent books are “American Carnage: The Wars of Donald Trump” (Opus Publishing, 2019) and “Containing the National Security State” (Opus Publishing, 2021). Goodman is the national security columnist for counterpunch.org.)