CommentsGUN VIOLENCE - The spate of mass shootings we've witnessed over the past few weeks has jolted our minds and broken our hearts.

The killings come in rapid-fire sequence, leaving us hardly a pause to catch our breath. In May alone, ten people at a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York; nineteen children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas; four at a hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma; and three at a church in Ames, Iowa. Over the first weekend of June, a medley of gun deaths dotting the country's landscape. Mass shootings, it seems, have become an American pastime.

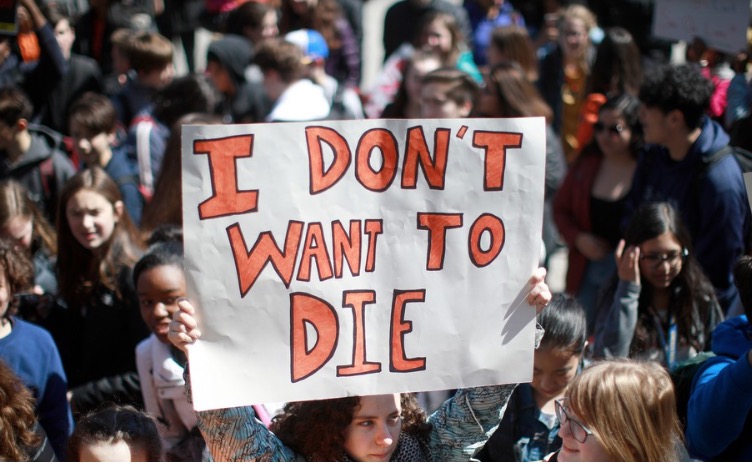

We now have to face the hard truth that here in America we're no longer safe anywhere. Not even in the most familiar places, not even when engaged in the most humdrum activities. Our churches, hospitals, supermarkets, and workplaces have all become danger zones. We can never be confident that when we go out shopping, we'll come home alive; that when we drop off the kids at school, we'll pick them up that afternoon. It's painful to write those words, but they're true.

Yes, mass shootings do occur in other stable democracies, but with nowhere near the frequency that we see here in "the exceptional nation." We must remember, too, that mass shootings are only a fraction of gun incidents in the U.S. Every day on average more than 110 people in the U.S. are killed with guns. Our gun homicide rate is eighteen times the rate of other developed countries. No other economically advanced country has such carnage.

While tightening access to guns would certainly help reduce the number of shootings in America, I want to explore the problem of gun violence from a different angle. What I want to determine is why the volume of gun violence is so high here in the U.S., to seek out the roots of this epidemic, the deeper causes that lie behind it.

We might look at the scale of gun violence in this country as the symptom of a deep malaise that has been gradually infecting the American psyche. The distant background to this malaise is the social ethos of this nation, with its celebration of individualism, aggression, and cut-throat competition. This ethos, which has become more pronounced over the past few decades, erodes the ties of empathy and solidarity essential to social cohesion. As a result, many in this country have come to suffer from a chronic sense of isolation and alienation. Rather than feeling connected to others, they find themselves drifting through life alone, forlorn and confused, with no one to turn to for support.

This stark individualism coexists with a more unifying vision that underlies our nation's spirit. This is the vision, expressed in the Constitution, "to form a more perfect Union … promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity." While we've often fallen short of these aspirations—very far short—until recently, I would say, a widespread conviction prevailed that we were moving in that direction. We rallied behind the New Deal, the New Frontier, the War on Poverty, the Great Society, the Civil Rights Movement. We were learning to affirm one another in spite of all our differences. We were moving forward together, as a nation.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, the bonds of a shared aspiration began to unravel; the social compact began to split. A resurgent conservatism took hold of the reins of power and replaced the liberal social project of the prior five decades with a neoliberal ideology that saw government action on behalf of ordinary people as a blunder. The idea that we were participants in a shared endeavor aimed at the common good gave way to a rugged, even ruthless version of market capitalism that extolled unregulated private enterprise as the driver of social progress.

The impact of this transformation on our national consciousness was profound. The change was not merely in economic policy but already started at the level of ideology. The proponents of neoliberalism changed the way we look at ourselves. They held that society is a mere abstraction constituted of inherently discrete individuals. They taught us to see ourselves as isolated individuals meandering through life without essential connections with others. We were like the atoms of classical physics, each self-sufficient, accidentally bumping up against each other under the impact of market forces. We have no obligation to others or the wider community. We were in it for ourselves and perhaps our immediate families.

Neoliberal economic policies widened the gap between the ultra-rich and everyone else. The rich saw their wealth and incomes soar; the middle class stagnated and shrank. Stable jobs paying good wages vanished as corporations moved their operations overseas. Once thriving cities and towns became wastelands. The gig economy reinforced the sense that we are each on our own, entirely dependent on personal initiative to avoid collapse. The one percent were like an insatiable monster that gobbled up the 99 percent and spit out their bones.

The original aspiration of the nation to advance "liberty and justice for all" gave way to a credo of "each against all," a struggle where private ambition trumps all other values. A symbiotic relationship emerged between the oligarchs and the political class, politicians relying on Super PACs for lavish contributions to finance their campaigns and reciprocating by serving the interests of the rich. The middle class and underclass look on helplessly as more stringent policies drive them downward and cement wealth and power in the hands of the few. For the wider population, cynicism usurps the place of hope.

The discrepancy between the ideals we profess, and the harshness of everyday life creates a tension that extends from the economic sphere to the personal. We're told that anyone who puts forth effort can succeed, yet we're handed a platter of cutbacks and austerity. We face constant pressure to do better, but the doors of opportunity are narrowed, and when we fail we judge ourselves losers, mere dross and flotsam in a system rigged against us.

The sense of abandonment spreads from individuals to communities and destabilizes families. Distrust, suspicion, anger, and fear multiply and infect the entire culture. We look around anxiously for feedback about our personal standing, afraid we might be canceled, mocked, dismissed as worthless. We try to dull the pain with drugs, cheap entertainment, and full immersion in the internet. To boost their sense of self-worth, some fall back on their heritage, skin color, ethnicity, or religion. But to their chagrin, they find that in a multiracial, multicultural society even these are losing their currency.

The resentment generates an identity crisis, the sense of an aggrieved identity which can be either collective or private. When it acquires a collective dimension, it becomes a crisis of group identity, which may easily push one toward right-wing extremism. The rhetoric of would-be autocrats and right-wing media personalities feeds the flames, whipping up hate against other groups seen to threaten one's endangered status. White supremacy rears its ugly head, congealing into militant groups that target people of color, immigrants, Muslims, or people who don't fit into neat binary gender types. "Those strange others," the castaways think, "are cheating us of the status and perks that are rightfully ours."

When the hatred infects an unstable mind, it might explode in racial violence or even a mass shooting: a paroxysm of destruction rooted in the fear that one's group status is in peril. The victims are mere innocent bystanders whose only offense is that they happen to represent a group seen as a threat to one's identity. Witness the Mother Emanuel AME church shooting in South Carolina; the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburg; and the Tops Market shooting in Buffalo.

For others, however, the sense of a wounded identity festers in private, directed against the self rather than toward a collective "other." Those afflicted with this type of identity crisis feel personally devalued, diminished, and abandoned, unable to connect even with a militant group. If the hurt crosses the bounds of rationality, it can lead to attempted suicide or the urge to retaliate against a society that denies one's self-esteem. A rude word, a mocking smile, a family dispute, or a failed romance can push the struggling soul over the edge. And with guns so easy to purchase, the outcome might be random homicide or, even worse, a massacre. Witness the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut; the Aurora movie theater shooting in Colorado; and the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

At bottom, I would contend, it's the wounded sense of identity, inflicted by the stark individualism of our culture, that breeds the type of mind capable of committing mass murder. From this perspective we can see these massacres and random shootings not simply as manifestations of ordinary mental health problems but as expressions of the aberrant, dehumanizing, dysfunctional values of our prevailing social ethos. This, I suggest, is the pathology from which we suffer, the malaise that lies behind our epidemic of random mass shootings.

If this analysis is anywhere near correct, then the remedy must include a far-ranging reconfiguration of our social ethos. Certainly, immediate practical steps are needed to reduce the number of deaths. The evidence is overwhelming that gun laws work. States with strong gun laws have low levels of gun violence; states with weak gun laws have high levels of gun violence. For a starter, we need a comprehensive ban on assault rifles and high-capacity magazines. We must make it more difficult for people with mental issues to get their hands on guns. We need rigorous universal background checks, training and tests for gun ownership, and stringent red-flag laws to restrict access to guns for those with troubled histories.

But these measures, as critical as they are, treat the symptoms of gun violence, not the root causes. They don't address the factors that incline people to commit random acts of murder, whether individual homicide or mass shootings. Tackling the problem at a more fundamental level calls for a radical transformation of our social ethos: from one built on competitive individualism to one that promotes a shared dedication to the common good.

Such a transformation might start with the economy. We need an economy that takes as its polestar the flourishing of all. We must ensure that everyone has access to the material requirements of a healthy life, that no one falls through the cracks. We're not a poor country. We can easily provide everyone with ample healthcare, housing, adequate food, a decent education, and a basic income.

But beyond this, what we require is a profound transformation of the reigning moral paradigm from one that valorizes competition, status, and material success to one that extols collaboration and cooperation. A change in values in turn hinges upon a change in our views, our understanding of ourselves and our relationship to our communities and the world. We must come to see ourselves not as isolated individuals pitted against others in a relentless struggle for dominance but as interdependent, interconnected beings whose happiness is closely connected with the happiness of others, whose flourishing depends on greater equity and a thriving biosphere.

The current social ethos that encourages the narrow pursuit of self-interest must give way to one that inspires empathy and compassion, that sees the good of self and others as inseparably intertwined. Such an ethos would expand the selective focus on material prosperity to encompass all the domains of value that enrich and ennoble human life. This must include the natural world, now being pillaged to expand corporate profits.

The move toward such a transformation might start in our schools. There's no reason the school curriculum can't educate students in altruistic values, with courses on the ethics of empathy and compassion. Such courses, drawing from the teachings of the great religions and the world's foremost moral philosophers, can inculcate in schoolchildren the values critical to a harmonious society. The curriculum should also include courses in civics, teaching the duties of responsible citizenship.

While we have no guarantee that such a seismic change in our social paradigm will put a complete end to murder, suicide, and other criminal activities, there is clear evidence that countries with greater social equity and economic equality have less crime, less alcoholism and drug use, higher levels of trust, and higher levels of life satisfaction than those with less equity and more glaring economic disparity. If we want to see whether such a change can work here, we need to put it to the test.

This is a task for government, which remains the expression of our collective voice. For all its drawbacks and inefficiencies, government is the only means available to us for ensuring the common good. Government is the means for enacting measures that express our essential unity and affirm our shared destiny.

You might cry out that our politicians will never enact programs that contribute to a more cohesive and equitable social order. Indeed, with our present crop of politicians, such changes are near impossible. But we should remember that we're the ones who put them into office in the first place, with our votes. They are in office to represent us. Thus the burden of making the changes we need ultimately rests on us. If we see clearly enough that our destiny, as a people and a nation, lies in our own hands, we might find the will power to take the necessary steps.

(Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is a Buddhist scholar and translator of Buddhist texts. He is also the founder and chair of Buddhist Global Relief, a charity dedicated to helping communities around the world afflicted by chronic hunger and malnutrition. This essay appeared in Helping Hands, the newsletter of Buddhist Global Relief.)