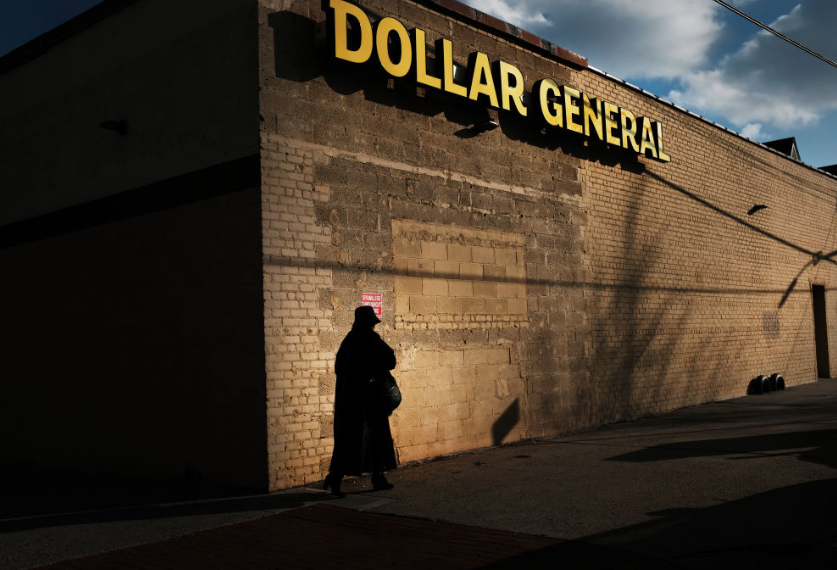

CommentsUNION MEMBERS - A handful of workers at the Dollar General In the small Connecticut town of Barkhamsted had grown frustrated last September at being poorly treated by a district manager, amid allegations that sexual harassment was ignored.

They became so upset that they sought to form a union to see that their concerns were addressed. But when they did, the massive retailer fought back with a vengeance.

The organizing effort involved just six workers (five after one said he was fired for his efforts to unionize) earning $13 an hour — so about $624 a day in total — but the company spent multiples of that to combat the union drive. Dollar General paid Labor Relations Institute, a firm known for its union avoidance consulting, a fee of $2,700 per day for each consultant it brought in, according to filings with the Department of Labor. LRI used five consultants, who reportedly held one-on-one meetings with workers and conducted group sessions to educate them on the risks of joining a union. In the end, the unionization effort failed and the company breathed a sigh of relief. The retail giant posted $33.7 billion in sales and $2.7 billion in profit in 2020, but remains convinced its future earnings might have been hurt if any of its 157,000 workers joined a union.

The company is just one of many that collectively spend hundreds of millions of dollars a year to make sure that its workers don’t organize. To take on the unions, they often hire consultants and law firms that specialize in tactics such as messaging, surveillance and intimidation. Companies spent an estimated $340 million a year on the cottage industry of consultants, some of whom charge $350-plus hourly rates or $3,200-plus daily rates. One consultant noted during a congressional hearing that the number of consultants had increased tenfold during the 1970s.

Such advisers have been around for many decades and their tactics have evolved, with an increasing use of surveillance technologies like social media monitoring and email tracking. But their approach remains essentially the same — relying on fear-mongering and intimidation.

They’ve been incredibly successful. Union membership has plummeted in recent decades, from 20.1% of American wage and salary workers in 1983 to just 10.8% in 2020. While anti-union consultants have played an outsized role, the country has also seen a decline in sectors like manufacturing that were once heavily unionized. In addition, regulators at the Department of Labor and the National Labor Relations Board charged with ensuring fair union elections have seen their budgets slashed and enforcement of rules regulating unlawful employer activities decline over the decades.

The decline started during the Reagan administration, remembers Patrick Byrne, a former official at the DOL. He recalls a supervisor walking into his office, pointing at a photograph on the wall of FDR talking to an unemployed worker waiting on a breadline during the Depression and snapping, “That’s old hat!” Byrne says that during the Trump era, his bosses ignored multiple reports of employers engaging in potentially illegal activity. “Over the years, the use of consultants has skyrocketed,” he says, adding that the agency has lost its sense of mission. “The New Deal paradigm is in cardiac arrest.”

Here are some of the most well-known companies in America and how much they’ve spent on union-busting firms.

These numbers represent just the tip of the iceberg — during the Trump administration, officials at the Department of Labor stopped requiring companies to disclose how much they spend on union avoidance consultants. As a result, the number of LM-21 filings plummeted 38% the year after the rule change — and many of those that were submitted left the dollar amount section blank. The Biden administration has yet to tighten the rules, despite signaling its intent last April to revisit these Trump-era changes. A spokesperson for the agency didn’t return a request for comment.

These partial spending numbers for anti-union consultants from 2017 to 2021 reflect the changing economy and now include many food delivery app companies and cannabis startups trying to cut their labor costs.

(MARCUS BARAM is a senior news editor at Fast Company and a former editor at the New York Observer, The Wall Street Journal, and the Huffington Post. He has also worked at the New York Daily News and ABC News, and has written for The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York magazine, Vibe, The Village Voice, and the New York Post. This story was published in Capital & Main.)