CommentsGUN CONTROL - Eighteen miles south of the Central Valley home that was her prison, down Highway 99 past almond orchards and trucks overloaded with hay bales, sits the Madera County Superior Court.

The four-story steel-structure with its light granite exterior boasts 10 courtrooms, large flat-screen monitors and a glass-skinned atrium. The courthouse opened in 2015 in this county of 160,000, part of a decades-long effort to shift funding and oversight of local courts to the state and ensure equal access to justice for all Californians.

“The Madera Courthouse was designed to demonstrate the transparency and dignity of democracy, providing a place to facilitate the workings of the American ideals of justice,” the architect’s website says.

Calley Garay, a 32-year-old mother of three young boys, came here in June 2020 seeking protection against her abusive husband.

Julio Garay warned her that a restraining order was nothing more than a piece of paper and wouldn’t keep him away, court records show.

But the beatings were getting worse, the threats more ominous, and local law enforcement was still investigating her allegations. She needed help. So in June of last year, planning for a new life with her children free from his control, Calley filled out the standard domestic violence restraining order request. Hers was one of 72,000 such forms Californians – mostly women – filed statewide that fiscal year, including 211 in Madera County.

We are now married or registered domestic partners. Check.

We are the parents together of a child or children under 18. Check.

I believe the person…owns or possesses guns, firearms, or ammunition. Check

The answer to that last question on Calley’s form told the court her case could be particularly dangerous. Research shows the presence of a firearm increases the likelihood domestic violence will turn deadly. It’s why people who are the subject of a restraining order in California – even a temporary one – aren’t allowed to have guns. By law, they are supposed to surrender their weapons to law enforcement or a licensed dealer within 24 hours of being served.

And if a simple checkbox wasn’t enough to grab a judge’s attention, Calley attached to the form more than a dozen pages of horror, including descriptions of assaults and photos of bruises on her leg, back and chest.

Through it all was mention of a gun – a gun in his pocket when he yelled at her outside their son’s school. A gun when he threatened to take her into the orchards and kill her.

What happened to Calley Garay – a story that culminated this week in the Madera courthouse – is about more than one woman. It’s about California’s inability to disarm abusers, a longstanding failure that judges, advocates and law enforcement have been warning about for years.

CalMatters spent months combing through government reports, reviewing case files in various counties, and interviewing people across the state. The reporting shows that equal access to justice is still elusive. The protections domestic abuse survivors get from the courts vary widely, depending on where they live or the judge handling their case.

And California, with arguably the toughest gun control measures in the country, too often struggles to enforce those laws.

In July, CalMatters reported on the state Justice Department’s difficulty clearing a backlog of cases in its Armed and Prohibited Persons System – a database of known gun owners who are barred from having firearms because of a conviction or other court order. At the start of this year, 24,000 people were in the system, including nearly 4,600 because of a restraining order. Those are just the people California knows about. It doesn’t include the many people – like Julio Garay – who abuse survivors say possess unregistered firearms.

In her request for a restraining order, Calley ended her description of a May 7, 2020, attack — the one that drove her to leave — by telling the court about fear.

“He has always told me that a restraining order is not bulletproof and that he will find me,” she wrote.

A month later, he did.I

Calley Jean Garay realized she had to escape in May of last year. Everything was getting worse.

The beatings were frequent and with whatever was at hand: June 2019, a belt. August 2019, a steel-toe boot. November 2019, a screwdriver. February 2020, a fire poker. May 2020, a black metal bar. In one attack, her 6-foot, 260-pound husband hit her so hard with a hair brush that it broke and flew behind her dresser.

CalMatters pieced together Calley’s story through interviews, state and federal court filings and sworn testimony. An attorney for Julio Garay said his client wouldn’t talk for this article.

Records show that almost anything could set him off. A misplaced receipt, coffee that was too hot, a truck that wouldn’t start. The first time he hit her – punching her glasses off her face while sitting in a Taco Bell drive-through in December 2012, shortly after they started dating – was after arguing on the phone with his prior wife. Another time he beat Calley because some men had cheated him in a car deal and Julio blamed her for not having his back.

Calley said he had a signal when he felt she was disobeying him and a beating was coming. He’d start tapping his foot on the ground.

If she stayed, there was only one way it was going to end.

“She was terrified that she was going to die if she didn’t get out of there and her kids were going to be killed as well,” said Sarah Rodriguez, 37, Calley’s cousin who grew up with her in Chowchilla, a city of 18,000.

Rodriguez’s mother, Terry Bassett, lived near the Garays in the quiet neighborhood of well-kept single-family homes. Bassett’s son was in the front yard in early May of 2020 when Calley – who might have lived a world away for how little she saw of the family by then – made a quick U-turn in front of him and told him to have her aunt come by to talk, Rodriguez said.

That conversation kicked off a flurry of calls and activity in Calley’s large family. They were getting their girl back, but she needed help.

Rodriguez said she and her mother rented a black Toyota SUV out of town and parked it away from the house. They reached out to a local victim services organization that helped arrange for a hotel room for Calley and the boys, then ages 1,4, and nearly 6.

The day of the escape would be May 15, 2020, when Julio, a truck driver for Save Mart, was working in Monterey. There would be a window between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. when he wouldn’t be checking in by phone to make sure she was home.

Julio Garay, left, next to his attorney in the Madera County Superior Court on Sept. 29, 2021, listening to testimony about his alleged domestic violence. Photo by Larry Valenzuela for CalMatters

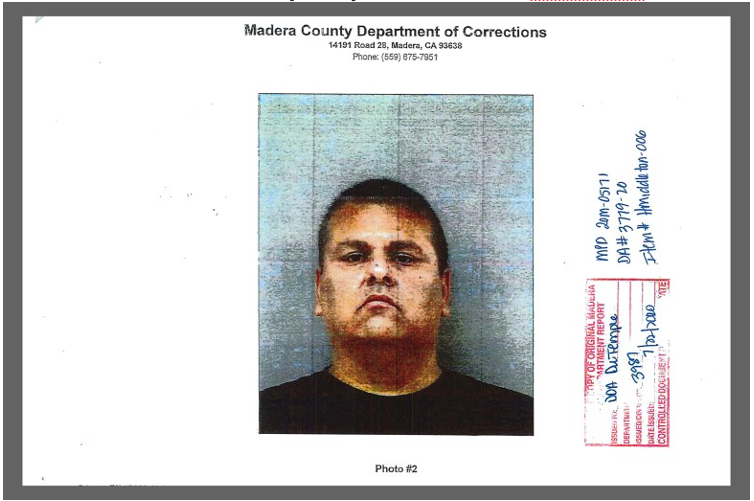

Julio Garay’s booking photo from the Madera County Department of Corrections. Image courtesy of the Madera County district attorney’s office

The aunt stood by the front window in the dark early morning waiting to see Calley come out of the house. But the time began to tick away…4 a.m… 5 a.m…. 5:30.

Bassett was in constant contact with Rodriguez. They wondered if they should knock on the door. But what if he’d come back?

Calley had tried to escape once before in 2015, the year the couple married. She went to the Chowchilla police and had criminal domestic violence charges filed against him. She also sought a restraining order from the family court in Madera, alleging he threatened to shoot her head “clean off.” But she had a 1-year-old son, was pregnant with a second and gave up on the restraining order, records show. Calley’s family believes he found out where she was hiding and forced her home.

Julio took a plea deal in the criminal case. The same day in 2016 that she was in a Fresno hospital giving birth, he was in a Madera courtroom pleading no contest to disturbing the peace “by loud and unreasonable noise.” He got off without jail time.

At 6 a.m. on May 15 last year, Calley finally emerged from the house. It turned out, she had forgotten to pack Julio chips in his lunch and he’d called to yell at her, telling her he was going to put her in the morgue, Rodriguez said.

The aunt rushed over, they loaded the three sleepy boys into the rented SUV and drove straight to the Chowchilla Police station.

Officer Ernest Escalera took the report. Over the course of an hour, she told him about the assaults and how Julio had warned that a restraining order wasn’t bulletproof, he would later testify.

“She was crying and stated that he was going to try and kill her,” Officer Escalera said. They did the interview in the lobby of the station because of COVID and Calley seemed distracted – watching the passing cars and saying she expected to see him. A female sergeant took photos of the bruises over Calley’s body.

The family then drove her and the children to the hotel.

(Robert Lewis covers justice issues. Before joining CalMatters he worked at print and public radio outlets across the country including WNYC-New York Public Radio, Newsday and The Sacramento Bee. His investigative reporting has garnered some of the industry’s highest honors including a George Polk Award, an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award and Sigma Delta Chi Awards.)