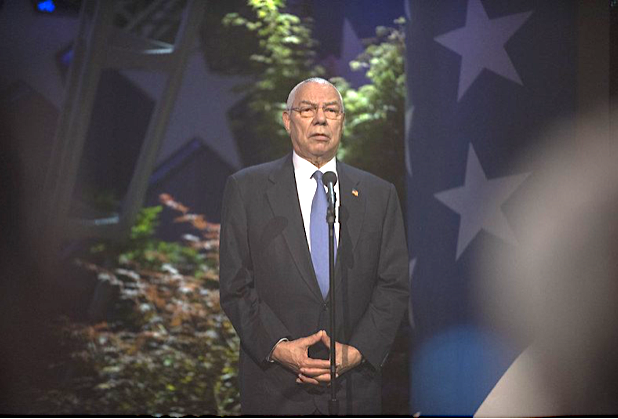

CommentsPERSPECTIVE - I still remember sitting at home with my parents and watching the news clips of Colonel Colin Powell presenting the U.S. case for war against Iraq.

I still remember all of us silently watching, as I (a teenager then), was feeling some level of connection to him, given he was the first black man I’d seen on TV with that level of influence and power, and I was a brown teenager now existing in the shadow of 9/11, facing off against white people yelling racist taunts at people in our community. I still remember how my mom and dad, speaking in Bengali, were torn, trusting him given he was non-white, but also, expressing confusion over what had been a dizzying run-up to the war, shifting in their seats.

Nearly two decades later, and with Colin Powell having now passed from complications with Covid-19, I now feel less confused, less uncertain obviously. After two decades of the War on Terror, after two decades of surveillance and rampant Islamophobia, after two decades of war, neoliberal decay, and the rise of Trump, due to the complicity of Republican leaders, some of whom Powell himself served (Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush), it is now evident to me that what Powell represents is a particular strand of “progress” for some and misery for nearly everyone else.

“General Powell was an exemplary soldier and an exemplary patriot,” President Barack Obama stated. Enter your email to subscribe to the CNN Newsletter The Point with Chris Cillizza.

“He was a great public servant, starting with his time as a soldier during Vietnam,” said George W. Bush.

As emphasized by Obama, Bush, and others across the liberal and conservative media, Powell’s life, which peaked with him becoming first Black secretary of state and the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, exemplifies a politics in which a person of color can indeed rise up the ranks, can make their impact, can earn praise and prestige, so long as they remain loyal to the project of U.S. empire, so long as they obviously do not push against certain types of thinking, such as the belief that the U.S. deserves to rule the world.

Essentially, what Powell represents is a type of racial progress narrative that eschews necessary discussions of U.S. power and hegemony. It is a type of racial progress that can easily fit into a possible future status quo politics, in which diversity is heralded by some, at the expense of major policy that would greatly improve the lives of the masses of people of color, domestic and global.

For instance, Powell’s rise began with his tour in Vietnam. The Vietnam War was a bloody attempt by the U.S. to maintain its influence in Southeast Asia. Although the U.S. had to eventually pull out its troops in a mad dash, it left behind millions of people dead, injured, and traumatized, mainly the Vietnamese.

Powell himself admits to participating in the cruel tactics wielded by the U.S. against the locals, including shooting people randomly from helicopters.

According to Jeffrey J. Matthews,

Powell’s book defended the practice of shooting male peasants from helicopters. If Vietnamese men, he wrote, wore “black pajamas,” “looked remotely suspicious” and “moved” after a warning shot, they were killed. “Brutal?” Powell asked. “Maybe so. . . . The kill-or-be-killed nature of combat tends to dull fine perceptions of right and wrong.”

It is important to emphasize that Powell served as an advisor during his tours in Vietnam. He wasn’t simply a grunt. He was someone who could speak their mind more clearly against the carnage that the U.S. had wrought on the Vietnamese who were fight for their country to be unified, and who had just kicked out their French colonizers.

His tours in Vietnam proved his worth to his superiors and over the decades, he would continue to be rewarded, promoted, and seen as an “expert” by many of his white peers, including Ronald Reagan, who appointed him as national security advisor. The Reagan administration, of course, continued the U.S.’s imperial ambitions and plunder, supporting right-wing death squads across central America, which led to the destabilization of the region, and much like Vietnam, the death of countless people.

As the late Kwame Ture said, Powell was a “hired killer” for the U.S. He played a role essentially in putting down those who were fighting against U.S. imperial machine, from the Viet Minh to left-wing forces across Latin America and across the world.

By the time he lied about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction, he had already been a significant force shaping U.S. foreign policy, and promoting U.S. national interests.

Yet, it is worth noting that Powell himself faced racial discrimination, as a black man, and his career did represent breaking the proverbial glass ceiling. It also cannot be denied that Powell’s life does carry significant meaning, because of his own quest against the “odds”. Even those who profess to be “progressive”, such as Jamaal Bowman, who stated, “As a Black man just trying to figure out the world, Colin Powell was an inspiration. He was from NYC, went to City College, and rose to the highest ranks of our nation.”

According to YouGov, Powell has been one of the more popular public figures among Americans. In the mid-1990s, the GOP, a party known for mobilizing white identity politics in its service of preserving a much more loony-bin style of capital, Powell had been encouraged to run. Especially then, Powell did have a significant shot at becoming our first black president.

The type of politics that Powell exuded, that one can climb up the ranks of U.S. society, one can be victorious against the slings and arrows of a political system dominated by whites, a system that for generations, looks down on, and sneers at non-white peoples, is not one restricted to him, of course. We also find it in the hagiography of figures, from Barack Obama to Andrew Yang to Kamala Harris, who stated this as much, when she launched the (justified) critique of Biden’s pro-segregationist past, and connected such policies to her own experiences a young girl of color striving for a better life, and having to confront forces that Biden supported.

Of course, broadly, there has been a long history of people of color being seen as exemplars, ironically, of the American Dream, as proof that society is meritocratic, or at the very least, it can change to allow some people into the halls of power. This type of “progress”/justice relies on a very narrowed conception of race/racism, of justice, of politics itself.

It very much relies on the idea that progress can be seen in black and brown people who’ve made it to the White House, who have made it into business, who are “entrepreneurs” (a la Yang). It depends on a conception of progress in which U.S. power is never question, in which such things as imperialism, capitalism, who has power in our society ultimately, is elided, if not outright dismissed. The fact is, Powell and others experienced hardship in their come-up, and they proved themselves capable. And this must be celebrated.

People tend to gravitate toward such narratives, not because they’ve been somehow brainwashed. Certainly, there is a level of propaganda that seeps into all of us, whether it’s racist ideas, or ideas about ourselves and the people around us.

But the ability for Powell to be seen as a hero, for Obama to still be taken seriously as a political leader, and for Yang and others to be seen as somehow representative or trustworthy to some, is a direct product of the lasty forty years of neoliberal policy, the repression of the Left, missed opportunities by the Left, and overall, the lack of alternatives to the status quo.

The reason why some people of color, including myself at one moment in my life, may have been more sympathetic to Powell was a combination of ignorance, propaganda, but also, not having the Left collective spaces that one would need to develop a political vision beyond the confines of what we have now: a battle between, what Nancy Fraser called, a more left-wing wing of neoliberalism and a more rabid form in the GOP and expressed from the mouths of loathsome figures like Tucker Carlson among others.

Ture, formerly Stokely Carmichael, had the analysis that he did, decades ago, because he emerged in a time when groups like the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords had existed. These were revolutionary Left organizations who spoke out against the U.S. war machine, against capitalism, and also, against forms of black and brown cultural nationalism, that in some ways, we see echoes of now in terms of celebrating Powell, that the only thing that does matter is having our black and brown business owners, our black and brown politicians.

Fred Hampton, one of the more prominent members of the BPP movement, whose life and assignation have been more well-known now following the success of Judas and the Black Messiah, once expressed in a speech to a crowd of people interested,

I mean, honestly, people, we’ve got to face some facts, that the masses are poor. The masses belong to what you call the lower class. When I talk about the masses, I’m talking about the white masses. I’m talking about the black masses. I’m talking about the brown masses, and the yellow masses too. We’ve got to face the fact that some people say you fight fire best with fire. But we say you put out fires best with water. We say you don’t fight racism with racism. We’re going to fight racism with solidarity. We say you don’t fight capitalism with no black capitalism. You fight capitalism with socialism.

Ture and other socialist black and brown leaders and organizations knew very well that one’s conception of justice, including racial, had to be broader than simply seeking out representatives, or believing in the success of others like a Powell, like a Yang, like a Harris, or even more ridiculous figures, such as Bobby Jindal or Nikky Haley, south Asian Americans who have been willing props for pro-business, pro-white nationalist, politics.

Having grown in New Jersey, I did start to realize, that a Desi owning a Patel Cash & Carry absolutely did very little for me or for those who work there when it comes to building a more liberatory society. Apart from providing food and ingredients that my family and I needed, even small businesses owned by a South Asian American were still institutions of exploitation and hoarding. As Marx understood it, all working people, whether in a Patel Cash & Carry or in a more white-collar pression, work for longer hours than they’ll be compensated for, and will always be at a power disadvantage as well, compared to the owner of the business. More importantly, the owner and their manages hoard the majority of the profits they earn, and so, as much as they provide food, at a price no less, most people who are South Asian will not benefit materially from the privatized success story of a brilliant “entrepreneur” who recognized its best to raise the price on cumin at a certain time of the season.

The concept of the “entrepreneur” is elevated by Democrats and Republican alike, and linking it to a narrowed conception of racial justice (i.e. buy Asian, buy black, buy Latino) is critical since it does open up some avenue for some people of color to become prosperous, or at least not dirt-poor, but doing so in a way that doesn’t challenge the overarching political system as it relates to labor, housing and healthcare.

Hence, one can see the U.S. as being “progressive” than decades before, with more diverse business owners, but nonetheless, the low wages, the horrid working conditions, the fact that rent moratoriums have been lifted during a pandemic, persist, and impact the vast majority of people of color.

The BPP, Hampton, and others had recognized this dynamic. They had recognized just how limiting this conception of racial justice can be, when capitalism is left to endure, when reforms now include elevating a business association, which reflect a sliver of what the general population needs.

The Biden administration, for instance, when discussing the impact of the economy on particular groups, such as Asian Americans, whose main worries have been healthcare and desiring more government intervention, can slide across vague statements of health equity and funding certain programs for people to access. Yet, he has a separate plank in his agenda about how to address concerns in the Asian American community by linking it directly to the idea of Asian business owners,

In 2010, the Obama-Biden Administration created the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) to support small businesses. The program transfers funds to state small business lending initiatives, driving $10 billion in new lending for each $1 billion in SSBCI funds. Joe will extend the program through 2025 and double its federal funding to $3 billion, driving close to $30 billion of private sector investments to small businesses all told, especially those owned by women and people of color. Joe will also increase funding for the Minority Business Development Agency budget. And, he will establish a competitive grant program to provide $5 billion in funding to states for new business startups outside of our biggest cities.

Providing money to Asian-owned businesses, as Hampton would’ve noted, will not uplift the community. It will not address many of the major concerns that Asians have, such as healthcare and the rising costs of living.

Yet, it is “progress”, according to the rubric of racial justice that excludes analysis of capital.

But possibly, the bigger critique that the BPP had was of U.S. empire. As much as their origins were in the domestic uprisings that swept through cities like Watts, the BPP leadership understood their struggle as being a broader global struggle against U.S. power.

The BPP leadership correctly identified how the U.S. domination of the globe was brutal and relied on suppressing movements, most of them socialist and communist, in Asia and Africa that were seeking redress and power after centuries of European plunder. They understood, just like their analysis at home, that they needed to side with not just any nationalists, certainly not those who were willing to work with the U.S. and seek “investment”, but with those who knew that true liberation wasn’t just about one group of elites being replaced with another. It was found in societies in which peasants and workers were no longer working for companies, and still finding themselves in abject poverty. It was found in movements, like the Viet Minh and the FLN in Algeria, who demanded power, not concessions, either from the Europeans or from those who locally benefited from colonial rule.

In Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. write,

The Panther’s line of Marx-inflected anti-imperialist thinking drew on a long line of black anti colonialist thinkers going back at least to W.E.B. Du Bois. This anti-imperialist perspective drove the world-changing Bandung Conference in 1955, was taken up by Malcolm X, and underwrote the Non-Aligned Movement, in which such international Panther allies as the postcolonial government of Algeria played important roles. The nondogmatic, Marx-inflected anti-imperialism of the Black Panthers allowed them to find common cause with many other movements around the world. It underwrote their practical political alliances with a wide rang of international movements.

The BPP saw clearly that the U.S. empire, domestic and abroad, stood in the way of liberation for the majority of people, especially those in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Siding with it, as explicitly as Powell had done in his life, or as Obama had done in his time as president, is not a sign of someone’s patriotism but rather, a sign of their loyalty to U.S. power and hegemony. Yes, progress can happen but it is one that is about only a few people allowed at the top, while everyone else sinks.

Socialism, not loyalty to empire, not acquiesce to non-reformist reforms (changes that don’t shift the balance of power, such as Biden’s infrastructure bill), is the answer. A socialism that is anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-colonialist. A socialism that will shut down U.S. military bases across the globe as well as pay reparations for U.S. harm, and of course, utilize resources to finally create an economy that is no longer bent on exploitation of the many, black, brown and white.

As Angela Davis said, decades ago, when the black Left was engaged in struggle with Nixon,

What I generally say, and I answered the brother and tried to explain in a few words why I was a communist, and I said, essentially, the same thing that I said when I told you why I was a revolutionary. Because I have a very strong love for oppressed people, for my people. I want to see them free, and I want to see all oppressed people throughout the world free. And I realize that the only way that we can do this is by moving towards a revolutionary society where the needs, and the interests, and the wishes of all people can be respected.

Of course, there are bright signs now of people starting to shake loose the neoliberal rust and decay. More and more people are turning toward socialism or at the very least, against capitalism, or against whatever they believe the current political system is (sometimes referred to by certain progressives as “crony capitalism). But the reality remains that there is still a lot to rebuild from the pasty forty years. With the retreat of the Left, a combination of its repression as well as its missteps (such as leaping into armed struggle when the best way to respond to the repression was deeper organizing in the community), and the diminishing power of institutions such as unions, it is no wonder that people are scrambling to find meaning, to find some type of story to keep them level, to keep them “hopeful” or sane. It is no wonder that this may lead some to identify with Powell or with Harris or with Yang and others like them. It is no wonder maybe some will fall prey to the storyline, despite their own lived experience, that they should see themselves in the political leader, in the community spokesperson, in the so-called “entrepreneur”.

For my own political journey, from liberalism to the Left, from believing that my future lay with more South Asians in politics (at least Democrat), to recognizing I deserve more (my people deserve more), it took educators, organizers, and friends/educators/organizers to get me to see more of the light. It took union campaigns and the DSA and protests for me to identify socialism, to identify what are my true interests and what would benefit those I love. Not another person of color fighting to prove themselves in the eyes of Uncle Sam.

What we need are organizations that could do the same for others, that could develop people beyond indifference and scrambling for meaning. Organizations that can also help people realize that a world must exist beyond the blood and guts of serving U.S. empire. A world beyond the dead bodies of black and brown people, of Vietnamese, of Iraqis. A world in which no one’s climb to fame should rely on others being collateral.

(Sudip Bhattacharya serves as a co-chair of the Political Education Committee at Central Jersey DSA and is a writer for CounterPunch.org based in New Jersey, having been published in Current Affairs, Cosmonaut, New Politics, Reappropriate, and The Aerogram, among other outlets. Prior to pursuing a PhD in Political Science at Rutgers University, he had worked full-time as a reporter across the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast.)