Comments

CALIFORNIA WORKERS’ COMP - (In the early 2000s, California’s massive workers’ compensation system was beset by both skyrocketing premiums to employers and declining quality of benefits for workers. In 2012, a group of reformers said, “Enough, this is crazy, the workers’ comp system is driving employers from the state and not benefiting workers”. Here’s what resulted.)

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the first truly successful reforms of California’s workers’ compensation. At the time of their passage, the reforms were denounced by opponents as “anti-worker” and “a giveaway to employers”. But now, ten years later, the data are in. The new system has reduced costs borne by employers. At the same time, it has significantly increased the monetary disability benefits that workers’ comp claimants receive, the speed and quality of medical care, and the speed of case resolutions.

The story of workers’ comp is a not unfamiliar one in this state and nationwide. For years, it was clear to all who were paying attention that the workers’ comp system was not effectively serving either workers or employers. What finally changed was that a number of appointed and elected officials, as well as representatives of labor and business, were willing to break ranks from the orthodoxies on government benefit programs. They said: “Enough, this is crazy, the workers’ comp system is driving employers from the state and not benefiting workers.”

Workers’ comp in California is a massive benefits system: more than 16 million workers are covered, and in 2021, 683,502 new claims (First Reports of Injury)were filed. It is a complex system, with numerous moving parts, not easily summarized. However, on this tenth anniversary, it’s worth noting briefly how the reforms were achieved, and lessons for other benefit programs.

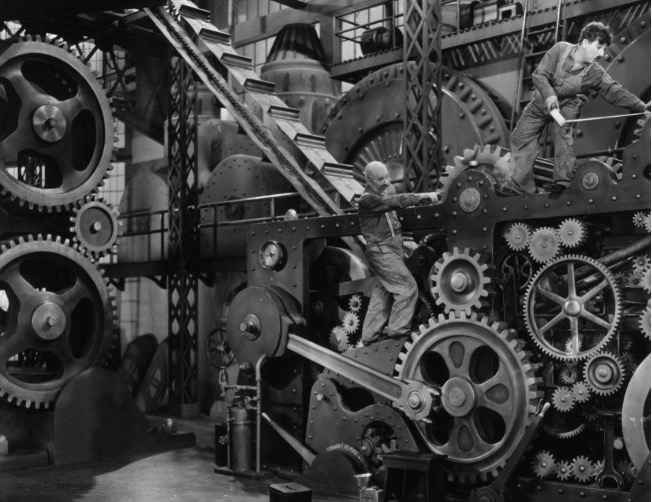

The system has its origins in the early years of the twentieth century. It was established in the California Constitution and first implemented by the “Workman’s Compensation Insurance and Safety Act of 1917”. It had as its main goals reducing the number of worker injuries, providing fair compensation to workers for their injuries and helping workers get back to work. The system incorporated the best thinking of the time by workplace experts. It was to be a streamlined no-fault benefit system with medical care and income replacement for workplace injuries.

Over time though, this envisioned workers’ comp system went the way of other government benefit systems. Little effort was made to control costs, since the costs were passed along to employers, whose protests largely were dismissed by state legislators. A sizeable bureaucracy arose, which had its own incentives to grow, and which lost sight of the system’s original goals of restoring the worker to health and employment. Perhaps most of all the system came to be taken over by a cottage industry of “middlemen”—attorneys, fee-for-service medical care providers, sellers of durable medical equipment and spinal hardware. These middlemen took advantage of the billing possible in an improperly incentivized and inadequately regulated multi-billion dollar system.

Christine Baker, the Director of the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) in 2013, played a central role in the landmark workers comp reforms implemented that year. She recalls, “By 2012, the system had become unnecessarily litigious with lengthy delays. Worker benefits were low, and the medical care was inconsistent and at times even detrimental to workers, a tragic example of which was unnecessary and often damaging surgeries. Workers in the system were often subjected to under care, over care, and care that was not justified by credible medical evidence of effectiveness.”

Baker had been drawn to DIR in the early 1980s, as a PhD. student at UC Berkeley with a strong interest in worker rights. She was hired in 1983, helping to retool the DIR’s information systems from paper-based systems to electronic ones. In 1987, she became chief of DIR’s Division of Labor Statistics and Research, and in 1994 she was chosen to be the executive director of the DIR’s Commission on Health, Safety and Workers’ Compensation, overseeing research on the workers comp system.

“As we studied the costs and benefit outcomes, we saw how workers’ comp had become a major business cost in California, limiting job creation and driving businesses elsewhere. At the same time, little of the money was finding its way to workers and the incentive structures for medical care had become skewed. Unscrupulous medical providers were billing for unnecessary treatments at the same time that many workers were not receiving adequate medical care. It became clear that both employers and workers had an interest in reforming the system.”

What Baker was able to do, with a number of other reformers, was to show that the out of control premium increases could be reversed, and at the same time disability payments increased to workers, along with improved medical care. A reform of the dysfunctional medical care system, along with sharp reduction of the frictional costs imposed by unnecessary ligation and predatory middlemen, could produce enough savings both for premium reductions and increased payments of benefits to workers.

The reforms mandated that medical care follow the most credible and effective evidence-based treatment guidelines available (produced by the non-profit ACOEM) as studied and validated by an independent organization (RAND). In addition, as part of ensuring that the ACOEM guidelines would be followed, disputes over medical treatment were removed almost entirely from litigation and decision making by judges who had little expertise and little interest in deciding treatment issues, often telling the parties to settle the dispute in the back room. The new procedure was to tender the analysis and decision to contracted independent medical experts with no financial interest in the treatment they prescribed.

Various other changes were made to standardize and improve medical care and speed the injured worker’s return to work, while eliminating practices that added unnecessary cost to the system, such as reforming physician fee schedules, placing restrictions on lien filings, eliminating duplicate payments for spinal surgery implant hardware, and controlling ambulatory surgical center fees.

The reforms, as set out in the legislation Senate Bill 863, proved to be highly contentious, with the opposition coming mainly from the associations of middlemen in the existing system. Baker held firm, and she was joined by reform advocates like Angie Wei of the California Labor Federation and Sean McNally, a lead spokesman for businesses supporting reform. They were able to convince both business and labor that the current system was not sustainable: rising costs to employers combined with limited benefits and uneven medical care for workers.

Len Welsh, who served as Acting Chief Counsel of DIR in 2012, after a 19 year career first as Counsel to Cal/OSHA and then as its Chief under Governor Schwarzenegger from 2003-2011, reflected recently on the hard fought battle that produced SB 863: “The negotiation we saw that produced these reforms demonstrated a fact that is all too seldom appreciated: Workers and the vast majority of compliant and regulatorily visible employers (as opposed to the underground businesses owners who regularly bilk the system, hide from the regulators, and jeopardize the safety and rights of workers), have tremendous interests in common that can get easily lost in the rhetoric of those who do not profit when these two drivers of society’s progress find common cause. Doesn’t matter whether you are preventing injuries or redressing them, the lesson to be learned is that the interests of employers and workers can converge a lot more often than they typically recognize.”

What have been the impacts of the reforms? The Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau of California (WCIRB), an independent research bureau, was given responsibility to track impacts starting in 2013, and in October 2019 pulled together its findings up to then in a major report. The report estimated that SB863 in the first five years since its inception had saved $2.3 billion to the workers comp system annually, and increased indemnity benefits by $900,000 annually. An estimated $10 billion of savings had been achieved through 2018. Other independent studies by the RAND Institute confirmed the financial and service benefits to workers, including higher replacement amounts of lost income provided to workers.

As well as benefiting workers, the reforms benefited employers, who saw a sharp drop in premiums. As the WCIRB researchers highlighted: “These savings have largely driven a series of advisory pure premium rate decreases totaling more than 40% and have resulted in the lowest average charged premium rates in the marketplace in more than forty years.”

Among the WCIRB’s more detailed findings on impacts since 2013: 28% Decrease in Overall Number of Medical Services, 85% Decrease in Overall Prescription Cost per Claim, 43% Decrease in Number of Claims with Opioid Prescription, 72% Decrease in Lab Tests. 39% Decrease in Medical Equipment Purchases, 30% Increase in payments for Physical Therapy, and 9% Increase in Physician Evaluation and Management Services.

Baker cautions that despite the improvements, there is no room for complacency and more to be done: “There are too many basic steps in moving through the system that become stumbling blocks, resulting in delay of treatment and delay of payment for treatment, which could be resolved through rethinking inefficient procedures, replacing paper documentation and filing with electronic information management, and implementing other changes to modernize the system.”

On this tenth anniversary, the California workers’ comp experience has lessons for workers’ comp systems in other states. It also has lessons for other government benefits systems, including, in California, the Unemployment Insurance system and Private Attorney General Act. These too were launched to benefit workers but have become ossified or been taken over by cottage industries of middlemen. Like workers’ comp, the reform of these systems will require breaking ranks. It will require ensuring that the money finds its way to workers, not to an overly complex administrative state structure and especially not to other parties.

(Michael Bernick served as California Employment Development Department director, and today is Counsel with the international law firm of Duane Morris LLP, a Milken Institute Fellow and Fellow with Burning Glass Institute, and research director with the California Workforce Association. Michael’s newest book is The Autism Full Employment Act (2021). This article was first featured in Forbes.com.)