Comments

The US housing crisis is at least 150 years old, dating back to the Civil War era.

PLANNING WATCH - I recently discovered an analysis of the country’s worsening housing crisis on a YouTube interview of Jeff Singer. Singer is a professor of social work at the University of Maryland and an expert on homelessness in the United States.

Singer makes the following points:

Since housing is a commodity built for profit in the United States, not to meet human needs, it inevitably results in homelessness. For example, after the Civil War thousands of homeless people roamed across the country. By the 1870’s they were called tramps and vagabonds, In fact, they were mostly young homeless white men who used the country’s new railroad system to look for work.

Charlie Chaplin, in The Little Tramp, released in 1915.

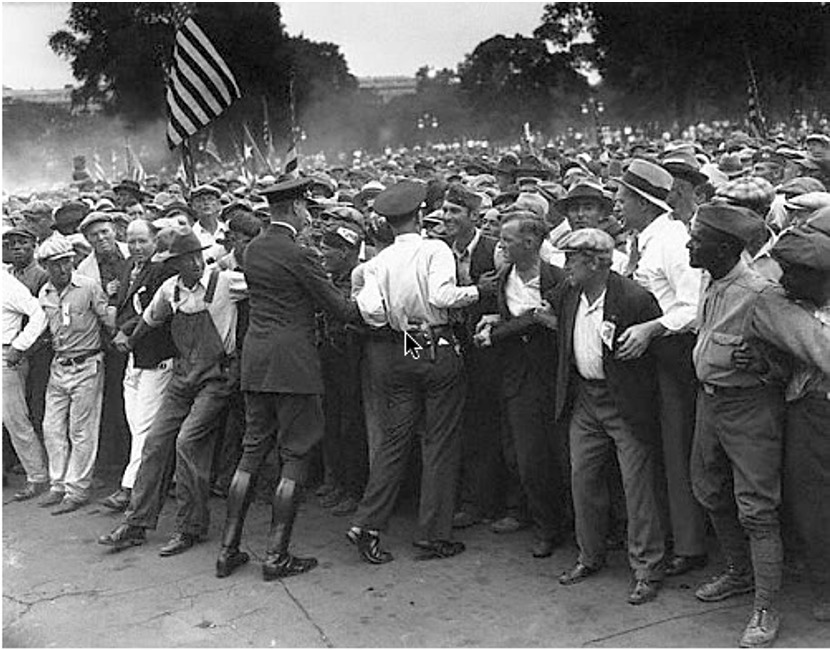

Homelessness became acute after WWI, when the homeless were called hobos, and their encampments were called Hoovervilles. The most famous Hooverville was in Washington, D.C, formed by WWI veterans promised a bonus for wages lost when they were soldiers. In 1932, 20,000 veterans formed the “Bonus Army” and built a large shantytown in Washington, DC. Generals Douglas MacArthur, George Patton, and Dwight Eisenhower led Federal troops to violently attack them and destroy their encampment.

May 1932 – US Army troops and police attack homelessness veterans in Washington, DC.

During the Great Depression, 1929-1941, homelessness quickly appeared, including in Los Angeles. Massive unemployment and homelessness resulted in the New Deal’s work programs and the Federal Housing Administration (1934). It funded and built public housing, much of it racially segregated. In Los Angeles the public housing built on Sawtelle Avenue in West LA was for whites, and in South Central public housing was for blacks.

After WW II the homeless were depicted as alcoholics, unlike the present, when they have been rebranded as addicts and mentally ill. While Urban Renewal programs eliminated most inner city neighborhoods where the homeless lived, LA was different. The city’s homeless population was confined to a 50 block area in the downtown.**

From the New Deal through the early 1970s -- when the Nixon administration terminated public housing programs -- the Federal Housing Administration built 1.1 million public housing units. Both political parties supported Presidential Nixon’s executive action, and the only housing program that survived was Section 8. It offers rent vouchers for private housing to low income applicants. But Section 8 is so underfunded that in 2022 the Los Angeles Public Housing Authority established a two week window for 30,000 Section 8 vouchers, anticipating 365,000 applications. Less than 10 percent of the applicants obtained a voucher, and 30 percent of them never found a landlord willing to rent them an apartment.

Professor Singer also points out that racism is central to homelessness. Even though the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed redlining and restrictive covenants, a large racial differential remained. For example, nine percent of LA’s population was black in 2022, compared to 30 percent of LA’s homeless.

Will homelessness finally end? In light of Professor Singer’s analysis, can we expect homelessness to soon disappear in the United States. Not likely - because the main beneficiaries of government housing policies are private sector contractors and landlords. These policies include:

- US foreign wars still produce homelessness. In addition to the costly proxy wars in Gaza and the Ukraine, since 9/11 the US has fought in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Somalia. The cost of these wars has been over $8 trillion, funds that could have been spent on mental health, employment, and public housing programs.

- Mansionization has continued, replacing existing homes with super-sized ones, tripling housing prices. In Los Angeles alone, there are now about 40,000 McMansions.

- Evictions total 1,000,000 per year, forcing residents out of houses and apartments, while raising housing costs.

- Up-zoning, which legally increases the amount of housing permitted on existing parcels, is marketed as the solution to homelessness. In fact, upzoning increases the cost of land, which results in overcrowding and homelessness.

Growing economic inequality also prices people out of housing.

This is why programs to reduce homeless have failed. They only treat symptoms and ignore root causes.

(Dick Platkin is a retired LA city planner. He reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He is a board member of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA). Previous columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions to [email protected].)

** The full history of homelessness in Los Angeles is carefully documented in the UCLA Luskin Center’s The Making of a Crisis: A History of Homelessness in Los Angeles.