CommentsNEIGHBORHOOD POLITICS--The Donald Trump administration may be committed to rolling back regulations that protect the environment, but Harbor Area and South Bay residents are ready to fight. The action at the South Coast Air Quality Management District meeting on April 1 regarding the PBF Energy Refinery in Torrance, is just the latest example.

About 50 of the 300 people in the room resolutely waved “Ban Toxic MFH” signs whenever MHF was mentioned by the board or speakers.

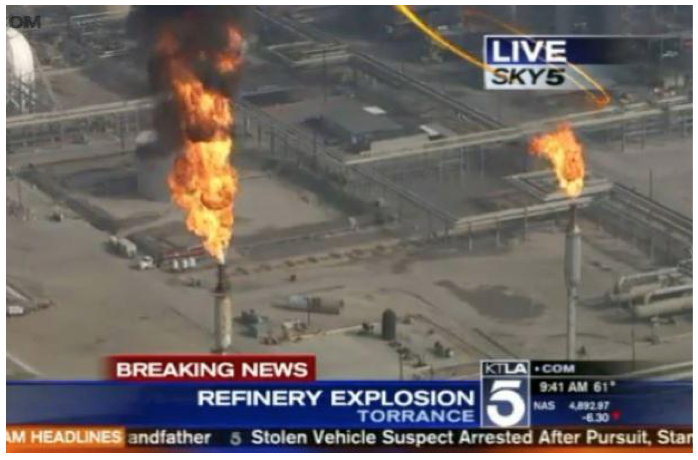

This meeting took place partly as a result of Torrance residents that became active following the former Exxon Mobil refinery explosion two years before PBF Energy took it over. In February, about 100 people marched in the rain to protest the refinery’s continued use of the alkylation catalyst, modified hydrofluoric acid or MHF. Representatives from the Environmental Protection Agency, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, the Los Angeles County Fire Department and PBF Energy gave reports at the hearing. The main topics were the refinery’s MHF, and public opinion on the chemical.

Speakers explained that in 2015, shrapnel from the explosion nearly pierced a tank containing MHF; a rupture or explosion of the tank would have released gaseous MHF that could have affected 30,000 people.

“MHF not only burns because it is an acid, it is a systematic poison,” said Sally Hayati, panelist at the hearing and president of the Torrance Refinery Action Alliance.

Fluoride ions from hydrofluoric acid easily absorb into human skin. They then bond with calcium in human bodies, making it unavailable; without calcium, cardiac arrest can result. Lungs can also fill with blood and water.

Laboratory scientists consider hydrofluoric acid to be one of the most dangerous chemicals to handle. Using EPA guidelines, Hayati and a team of other scientists determined that the worst case scenario from an MHF release would be lethal exposure.

Since the explosion two years ago, the Torrance Refinery Action Alliance has informed the community of MHF’s potential danger as a refinery catalyst. Their campaign has been successful, prompting government officials to respond to the will of the people.

“My No. 1 priority is to make the people safer,” said Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi, who represents Torrance. “I have introduced a plan to the Assembly to not just make [the PBF refinery] safer but all refineries. That includes a ban on MHF.”

Muratsuchi’s plan consists of five Assembly bills: AB 1645, AB 1646, AB 1647, AB 1648 and AB 1649. In addition to banning MHF, the other bills would call for real time air quality monitoring, a community alert system, more refinery inspectors and codification of Gov. Jerry Brown’s Interagency Refinery Task Force.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn, who was also present at the SCAQMD hearing, supports Muratsuchi’s bills.

“This is personal for me … it involves the safety of my constituents,” said Hahn. “It’s a common sense plan.”

Elected officials from Torrance, including the mayor, were in attendance as well. On March 28, the city council voted against a phase out of MHF. However, Mayor Patrick Furey told SCAQMD board members and the audience about two resolutions the council adopted. One encourages the refinery to adopt safety measures. The other supports regulations that include a safer catalyst than MHF.

Safer catalysts include sulfuric acid and solid acid. Laki Tisopulos, an engineer with the SCAQMD, and Glyn Jenkins, a consultant with Bastleford Engineering and Consultancy, discussed each catalyst and its potential to replace MHF.

They said that sulfuric acid has been used instead of MHF to refine fossil fuels for decades. Out of the 18 refineries in the state of California, 16 use sulfuric acid. Converting the PBF refinery would cost between $100 million and $200 million.

Solid acid technology is newer. But Jenkins said that there is a refinery in the United Kingdom that successfully refines fossil fuels with it. The same refinery switched away from MHF because it was considered too risky. Like the name suggests, the solid acid process uses a solid catalyst. No acid clouds would result from an explosion, making it safer than either the gaseous MHF or sulfuric acid.

Tisopulos estimated that converting the PBF refinery to use solid acid would cost $120 million initially. Additional costs would come whenever the catalyst had to be replaced.

PBF Energy has not embraced the idea of switching catalysts. In an advertisement in the Daily Breeze, the company stated, “We are confident that the many layers of protection, mitigation steps, and safety systems we have in place allow us to operate the MHF Alkylation Unit safely…”

Their own estimate for converting to another catalyst was around $500 million.

“The discourse [between PBF Energy and the community] has been if the chemical is changed, we lose jobs,” Torrance Councilman Tim Goodrich said.

Fearing any potential job loss, various refinery workers and union members stood up during the hearing’s public comment section and said that they support the status quo. They feel the refinery is safe enough and that the explosion this past year was a fluke.

“…[T]here is no reason why MHF can’t be phased out while jobs are protected,” Hahn responded. “I believe the switch will accelerate newer and safer alternatives, innovation, and lead to better jobs.”

Muratsuchi agreed. He said he doesn’t want to see the refinery shut down, but it should be safer.

In November 2016, the EPA inspected the safety of the PBF Energy refinery.

“They were not following their own safety procedures,” said Dan Meer, assistant director of the Superfund Division of the EPA.

The EPA released a preliminary report on the inspection in March.

“There are issues the refinery needs to address,” Meer said. “If I had to a rate the current risk, with 10 being an emergency situation, [PBF] would be somewhere between a 5 and 7.”

Meer went on to explain that PBF did not have permits to store certain chemicals it has on site. Management is also not effectively communicating with workers, which could be dangerous in an emergency situation. PBF has until the end of April to respond to the EPA and make changes. Otherwise, the EPA will take administrative and legal action.

“This is an urgent public safety risk,” Hayati said. “The refinery should not be in operation at least until the EPA verifies that procedures are being followed.”

Although the local United Steelworkers don’t want to change the catalyst, the steelworkers at the international level feel differently. A study completed by United Steelworkers found 131 HF releases or near misses and hundreds of refinery violations of Occupational Safety and Health Administration rules.

“The industry has the technology and expertise [to eliminate MHF and HF],” the report stated. “It certainly has the money. It lacks only the will. And, if it cannot find the will voluntarily, it must be forced by government action.”

Los Angeles Harbor

The SCAQMD has plans to release an environmental impact report on the Tesoro Corporation’s desire to combine its Wilmington refinery with the former British Petroleum refinery in Carson. Environmental organizations view the report as flawed and will call attention to Tesoro’s plans at the Los Angeles People’s Climate March on April 29.

In 2012, Tesoro purchased the refinery in Carson. Tesoro’s expansion into that site would include adding storage tanks to hold 3.4 million barrels of oil.

Communities for a Better Environment and other climate advocates oppose the expansion. But the focus of the march will be to inform the people about Tesoro’s lack of accuracy and transparency in detailing the project’s impacts to the SCAQMD.

“Tesoro has said that this project is going to reduce emissions and will be ‘cleaner,’ but they admitted to their investors that they are switching to a dirtier crude,” said Alicia Rivera, a community organizer with Communities for a Better Environment.

In a presentation to investors, Tesoro called the type of crude oil, “advantaged crude.” The advantage is that it is cheaper than standard crude. The new type of crude will originate from the Canadian Tar Sands and the Midwest’s Bakken Formation. (About 75 percent will come from North Dakota and 25 percent will come from Canada.)

“These fuels have different characteristics than what Tesoro is refining [in Wilmington] now,” said Julie May, senior scientist with Communities for a Better Environment. “They behave more like gasoline. They contain more benzene, which is a volatile organic compound that causes leukemia.”

The draft environmental impact report that Tesoro submitted to the SCAQMD does not clearly mention a crude oil switch. In a comment letter to the SCAQMD, May explained that this failure does not meet the California Environmental Air Quality Act’s project description requirements. Consequently, no one can properly analyze the switches’ impacts, environmental effects and risks to community and worker health and safety.

Another major reason Communities for a Better Environment wants to march against Tesoro is the corporation’s failure to properly evaluate the scope of the project. If the environmental impact report is approved, the refinery will receive fuel via ships traveling from Vancouver, Wash. Vancouver is the site of a rail-to-oil tanker terminal in which Tesoro and Savage Energy invested.

“That [terminal] is the bridge to bring dirty crudes from North Dakota and Canada,” Rivera said. “We call the rail cars that transport the fuel ‘bomb trains’ because some have derailed and exploded.”

Refineries and projects like this undoubtedly have an impact on Harbor Area residents. The challenge now for Communities for a Better Environment is getting residents to come out to the march. Rivera and other Communities for a Better Environment members acknowledged that many of residents are immigrants or working class people; for them, climate change is not always a tangible concept nor an immediate concern.

But Communities for a Better Environment is determined.

“We have youth members going to elementary and middle schools and colleges,” Rivera said. “We are pamphleting markets and Catholic churches. When we inform [people] about this project, they want the expansion to stop.”

On the day of the march, Communities for a Better Environment will circulate a petition to marchers. Its purpose is to pressure the SCAQMD to take Tesoro’s EIR back to a draft stage. Then it can properly detail the project and allow for public input.

The SCAQMD has the authority to finalize the EIR before the march. But that won’t stop Communities for a Better Environment from trying to get the community engaged.

“We need to bring attention to local industries trying to expand in a time when they should be cutting down their emissions,” Rivera said. “Tesoro’s Los Angeles refinery is the highest greenhouse polluter in the state. If the project goes forward, it will be the largest refinery on the West Coast.”

(Christian L. Guzman is community reporter at Random Lengths … where this report originated.)

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

19

Fri, Dec