THE NELSON RISING METHOD--What do we do now, Nelson Rising?

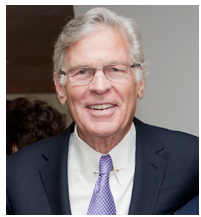

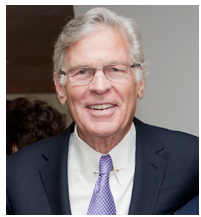

I pose that question not just because this is a confusing and complicated era for California. And not just because no living Californian is better than Nelson Rising—a developer, lawyer, campaign manager, and civic leader from Los Angeles—at navigating our state’s complexities to create communities that endure.

“What do we do now?” is the question that concludes Rising’s one-and-only brush with Hollywood. After Rising ran the successful 1970 U.S. Senate campaign of John Tunney, he was a producer on the 1972 film The Candidate, in which Robert Redford plays an idealistic U.S. Senate candidate corrupted by the political process. When Redford wins an upset victory, he is so empty that in the final scene, he asks his campaign manager, “What do we do now?” The manager has no answer.

Fortunately, Rising, 75, has some reassuring answers about today’s California, as I learned during two recent long conversations. And if you’re a reader who doesn’t know the name Nelson Rising, don’t worry—that’s the point. Nelson Rising’s story is about all the big things you can get done in California if you’re willing to listen more than you talk. Over the years his impressive accomplishments have spoken for themselves, without much ballyhoo for the man himself.

Fortunately, Rising, 75, has some reassuring answers about today’s California, as I learned during two recent long conversations. And if you’re a reader who doesn’t know the name Nelson Rising, don’t worry—that’s the point. Nelson Rising’s story is about all the big things you can get done in California if you’re willing to listen more than you talk. Over the years his impressive accomplishments have spoken for themselves, without much ballyhoo for the man himself.

When you tally up all the big things Rising has helped bring to California, there are simply too many for a short column. You could start with the tallest building in the state, the Library Tower (now the U.S. Bank Tower) in downtown LA. You could throw in Grand Park, LA’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Metropolitan Water District buildings, and the Playa Vista development (now unofficial headquarters of Southern California’s Silicon Beach). You might add San Francisco’s Mission Bay, the largest mixed-use development in that city’s history, and, in San Diego, two mixed-use towers, next to the train station, that were part of the wave that transformed downtown into a thriving residential neighborhood.

But then you’d still be leaving out major developments like Rising’s first big project, Coto de Caza, the quintessential suburban Orange County planned community, made famous through reality television. (“He is to blame for The Real Housewives of Orange County,” says Rising’s son Chris).

And the buildings are just part of his legacy. In LA, Rising managed the mayoral campaign of Tom Bradley, the city’s first African American mayor, who transformed the city into a far more international, educated, and inclusive place. During a stint up north, Rising was chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (where he navigated the disruption of the dot-com bust), chair of the Washington D.C.-based Real Estate Roundtable, chairman of the publicly traded real estate firm Catellus, and chair of the Bay Area Council, a vital business policy group. His sport coats have put the blue in countless blue-ribbon commissions, and he’s led efforts to remake policies on projects as varied as water, redevelopment, and LA’s Grand Avenue.

Rising’s remarkable career stands as a rejoinder to the maddening conventional wisdom of today’s California: that you can’t do big things in our state because everything is too complicated, regulated, and expensive. Any big project requires dealing with too many different constituencies. Who has time to talk with everyone, much less dig into all the details and accommodate all the interests that must be accommodated?

Nelson Rising makes the time.

Which is the secret of success in California. Rising argues that because so few try to do the big, complicated thing, those who are willing to do all the hard work¬—to talk with everybody, to accommodate every opponent, to sweat every detail—can still accomplish great things. In fact, Californians are so used to having their concerns ignored that the act of listening to and working with one’s opposition can be incredibly powerful.

“I enjoy communication, and the best part of communication is listening. Many people don’t do that,” says Rising. “I don’t think I can respond to people unless I know what I’m responding to. So I always start the conversation by asking, ‘What’s your concern? Why don’t you want me to do this development? And if I can figure out a way to solve your concern, will you be supportive of it?’”

Rising’s natural—if quite deliberate—modesty makes this approach particularly effective. In our recent conversations—at his downtown LA office and at the California Club—Rising deflected credit or understated his role, depicting himself as a coordinator of teams that did the real work. Colleagues interjected frequently to say he was being too modest.

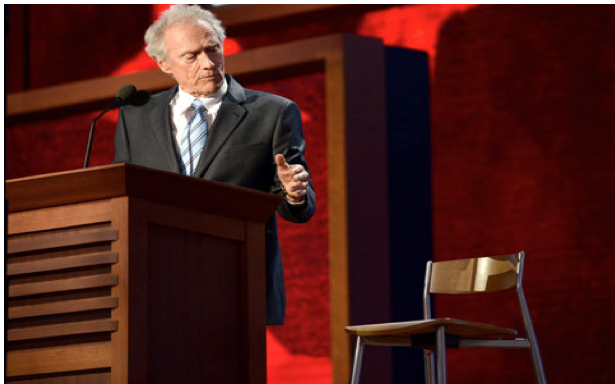

But modesty suits the man, who might be the polar opposite of the real estate developer currently occupying the White House. Rising’s parents never attended college; he went from Glendale High to UCLA and later UCLA law school on a scholarship. He’s been married to the same woman for 53 years and lives in La Cañada-Flintridge, far from the fancy Westside precincts favored by other movers and shakers.

He credits his rise to good fortune, good co-workers, and the friendship of Warren Christopher, a colleague at the law firm of O’Melveny & Myers, who brought him into civic and political work, originally through an effort to rebuild the Democratic party after Ronald Reagan defeated Gov. Pat Brown in 1966. “A person cannot be truly accomplished unless they help others to accomplish,” was a Christopher maxim that Rising still recites.

Rising sees his own skill as building teams that help others accomplish, and that accomplishment comes from talking to one’s opponents. That may seem like very old wisdom, but it is revolutionary today, when civic and political contests are often about rallying one’s base of supporters, while discouraging the base of opponents. He says Tom Bradley succeeded because he visited every corner of the city and made a point of engaging people who were inclined to oppose him—over time, the constant reaching out made Angelenos comfortable with him.

There are similar stories of engagement—of embracing conversation and complexity—in Rising’s other successes. He made the Library Tower (and the neighboring Gas Company tower) happen by arranging a complex swap, in which the tower’s builders purchased the air rights to develop above LA’s Central Library, located across the street, and used them to increase the height of the towers. Revenue from the sale helped the library rebuild after a crippling fire.

Rising argues that because so few try to do the big, complicated thing, those who are willing to do all the hard work—to talk with everybody, to accommodate every opponent, to sweat every detail—can still accomplish great things.

Having developed the tallest building in the state, however, did not make Rising self-important. To win approval for the Playa Vista project, he went into living rooms to meet with homeowners in Westchester, who were angry about the vast amounts of multi-unit housing in his plan. He slowly wore down resistance with conversation and with a presentation that used two slide projectors—to show not only the before and after, but also attractive multi-unit housing in places like Savannah and Washington D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood.

The greatest example of the Rising method may be Mission Bay. As the CEO of the public real estate firm Catellus, he took over a development that faced opposition and remade it to satisfy the complaints of San Franciscans. His moves included adding 1,700 units of affordable housing, providing parking for Giants games, and donating 43 acres to UC San Francisco for their biotech campus. The development was ultimately approved without opposition; there wasn’t a single environmental lawsuit.

The feat was so impressive that San Francisco—a place where throngs chant “Beat L.A.” with little provocation— named a street in Mission Bay after the Los Angeles developer—Nelson Rising Lane. “You can walk all over Nelson Rising,” quips his longtime colleague David Herbst, “but you have to go to San Francisco to do it.”

Rising cops to plenty of failures, including twice flunking attempts at retirement. So now he’s building a business with his son Chris, who is named for Warren Christopher. They are raising a $300 million social impact fund for investments, and are focused on three things: Remaking buildings so they produce less carbon (“We’d like to show the real estate industry it doesn’t have to be the number one generator of carbon,” Chris says); making buildings healthier (with more light and air, and designs that are better for workers); and incorporating technology into older, restored places by taking all the copper out and replacing it with fiber networks. (Their revamping of One Bunker Hill in LA will include a signature public lobby with powerful Wi-Fi that they want schoolchildren to use to do their homework.)

Rising remains loyal to downtown LA, and marvels at how the area, once almost entirely an employment hub, has surpassed all expectations by becoming a place to live. He praises the Wilshire Grand Center that, when it’s completed later this year, will supplant the Library Tower as the state’s tallest building.

Rising still works in the historic Beaux Arts PacMutual complex that he restored and then sold in 2015, reportedly at a record per-square-foot price for a downtown office building. His firm has since purchased 433 S. Spring, an Art Deco building where Rising began his career as an O’Melveny lawyer.

The firm is working in LA, San Diego, and San Francisco, and eyeing Sacramento, where the Risings have been impressed with the growth of its downtown. He is critical of President Trump’s policies, but doesn’t think the new administration will be able to undermine California too much. “The state’s economy is poised to keep exceeding the country,” he says, as long as it keeps nurturing its diversity, raises its education levels, and rebuilds its infrastructure.

So what do we do now, Los Angeles … California? We follow Rising’s singular example: Reach out to one another, listen—and recommit to doing the big things that will make a difference.

(Joe Mathews is Connecting California Columnist and Editor at Zócalo Public Square … where this column first appeared. Mathews is a Fellow at the Center for Social Cohesion at Arizona State University and co-author of California Crackup: How Reform Broke the Golden State and How We Can Fix It (UC Press, 2010).)

-cw

Fortunately, Rising, 75, has some reassuring answers about today’s California, as I learned during two recent long conversations. And if you’re a reader who doesn’t know the name Nelson Rising, don’t worry—that’s the point. Nelson Rising’s story is about all the big things you can get done in California if you’re willing to listen more than you talk. Over the years his impressive accomplishments have spoken for themselves, without much ballyhoo for the man himself.

Fortunately, Rising, 75, has some reassuring answers about today’s California, as I learned during two recent long conversations. And if you’re a reader who doesn’t know the name Nelson Rising, don’t worry—that’s the point. Nelson Rising’s story is about all the big things you can get done in California if you’re willing to listen more than you talk. Over the years his impressive accomplishments have spoken for themselves, without much ballyhoo for the man himself.

They project that LA County could suffer a potential three-year loss of 800,000 international visitors as a direct result of President Trump’s Executive Orders. These visitors typically spend $920 each while in LA, totaling a potential loss of $736 million in direct tourism spending.

They project that LA County could suffer a potential three-year loss of 800,000 international visitors as a direct result of President Trump’s Executive Orders. These visitors typically spend $920 each while in LA, totaling a potential loss of $736 million in direct tourism spending.

Stay Off Our Lawn! California officials thereby have concluded that the state cannot be compelled to use its police or military forces for law enforcement purposes; in their analysis, controlling immigration is a federal responsibility, not a matter for state or local law enforcement.

Stay Off Our Lawn! California officials thereby have concluded that the state cannot be compelled to use its police or military forces for law enforcement purposes; in their analysis, controlling immigration is a federal responsibility, not a matter for state or local law enforcement.

It’s a mess and Ryu (speaking to MMRA meeting photo left) is right in the middle of it. The ground has suddenly shifted from the original dispute about HPOZ boundaries -- that were reset in December by David Ambroz and the Central Planning Commission -- to Ryu now asking the very basic question, “who wants a Miracle Mile HPOZ?” Results of Ryu’s poll will be revealed at a community meeting he has called for February 22, at 7p.m. in the auditorium of John Burroughs Middle School. Both the Miracle Mile Residential Association and Say No HPOZ are mobilizing for what could be a showdown with Ryu, who is now in a tough position.

It’s a mess and Ryu (speaking to MMRA meeting photo left) is right in the middle of it. The ground has suddenly shifted from the original dispute about HPOZ boundaries -- that were reset in December by David Ambroz and the Central Planning Commission -- to Ryu now asking the very basic question, “who wants a Miracle Mile HPOZ?” Results of Ryu’s poll will be revealed at a community meeting he has called for February 22, at 7p.m. in the auditorium of John Burroughs Middle School. Both the Miracle Mile Residential Association and Say No HPOZ are mobilizing for what could be a showdown with Ryu, who is now in a tough position.

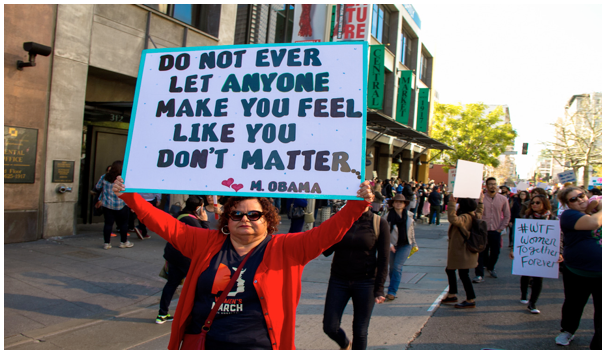

First, it is obviously important that Indivisible grows in number. It's standard to compare organizational strength to the National Rifle Association. They should make it a goal to grow to at least that size. But it's also important that the resistance to Trump's policies continue to grow outside of the big cities on the two coasts. Therefore, people who are willing to join the opposition should reach out to people who live in political border areas, the places that the news media traditionally refers to as purple (for their near balance of liberals and conservatives). Whether it's relatives or old classmates, online chums or army buddies, it's important for participants to make the effort to bring in at least one or two new people.

First, it is obviously important that Indivisible grows in number. It's standard to compare organizational strength to the National Rifle Association. They should make it a goal to grow to at least that size. But it's also important that the resistance to Trump's policies continue to grow outside of the big cities on the two coasts. Therefore, people who are willing to join the opposition should reach out to people who live in political border areas, the places that the news media traditionally refers to as purple (for their near balance of liberals and conservatives). Whether it's relatives or old classmates, online chums or army buddies, it's important for participants to make the effort to bring in at least one or two new people.