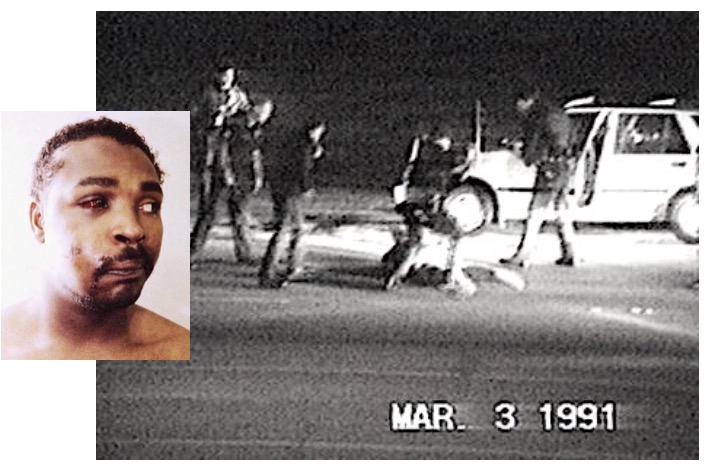

CommentsREVISITING LA UPRISING - Thirty years ago this week, four Los Angeles Police Department officers (Sgt. Stacey C. Koon, Officer Theodore J. Briseno, Officer Timothy E. Wind and Officer Laurence Powell) were acquitted of brutally beating a Black man by the name of Rodney King.

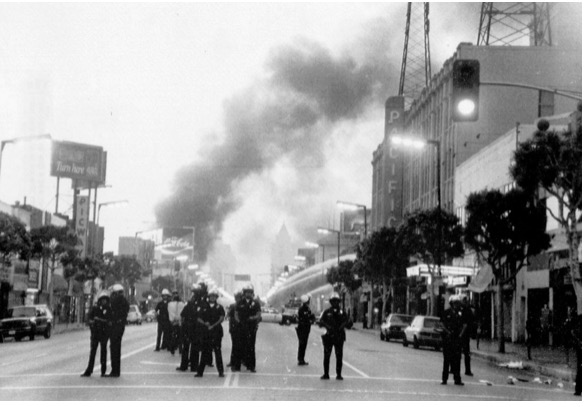

The response in the streets of Los Angeles were both immediate and surprising as the residents of the city had witnessed one of the first video recorded examples of police brutality the year before and had waited for justice to be served in our superior courts. None seemed to be had as the fury related to the not guilty verdicts poured out into the streets, resulting in five days of rioting in Los Angeles. It reignited a national conversation about racial and economic disparity and police use of force — a conversation that was being had in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion in 1965 — and its a conversation that we continue to have today.

In the wake of the Watts Rebellion, city leaders thought utilizing more militarized training would make the city safer. Chief Daryl Gates, if you don’t recall, is considered the father of the modern SWAT teams that exist in police departments across the country. SWAT was outfitted with anti-sniper units that are on-call to protect police stations and fire equipment and retaliate against rioting snipers during times of civil unrest. Since then, they are utilized in drug raids and executing no-knock warrants with dubious success.

Anyhow, a few years before the ‘92 Rebellion, I often found refuge from a day’s work at Antes Restaurant, the last of the Croatian eateries in San Pedro. It was one of the great retro bars with a sunken well backed up with a full complement of liquors, a friendly bartender who knew your name and where longshoremen and women could sit eating and drinking at the bar. It often held a cast of characters that was as real as the people who worked the waterfront and the streets of San Pedro.

One particular character was a former LAPD officer by the name of Rod Decker who notoriously used to brag about his exploits of beating up Black and brown residents, explaining his accomplishments with a string of derogatories that I won’t repeat.

Most of the time the locals just ignored him as a blowhard. And yet one evening while I was sitting at the bar he went off on one of his racist rants. I looked around the bar at the Filipino bartender, Eddie, and down the row of ethnic patrons, I stood up, threw my hat on the bar and spoke quite directly, “Decker, I’ve had enough of your goddamn racist shit, so shut the fuck up!”

You could have heard a pin drop. Eddie busily hurried to wash some glasses and everyone else was just staring in their drinks waiting for some retort or perhaps a fight to break out. There was none, but in the weeks that followed every time I entered the bar Decker had some wisecrack to lodge in my direction about being a commie-pinko or worse. And I’ve heard worse from better people than him.

So it came as some surprise on the very night of the TV reports on the Rodney King beating in March 1991, you’ll recall the video was replayed ad nauseam. Today you’d say it went viral.

I walked into the bar at Ante’s and Decker, seeing me in the reflection of the mirror behind the bar, turned and said quite bluntly in effectuated Spanglish, “Nolo contendere partner, that was not even a righteous bust.” The King beating was far too brutal or blatant for even this racist cop to stomach. That says a lot about what happened a year later when the officers were all acquitted in a Simi Valley courtroom and the streets of South LA exploded.

The Los Angeles Police Department was totally unprepared and disorganized. Then the governor called out the National Guard and finally the United States military was dispatched. It was reported back on the 25th anniversary by NPR that, “When 911 calls about the violence started coming in, police were not deployed immediately. Though LAPD Chief Gates announced early in the afternoon of April 29 that his officers had the situation under control, it would later be reported that the city was not adequately prepared for the riots. In fact, there was no anticipation of — or official plan at the department for — major social unrest on this scale.”

Here in San Pedro far, but seemingly not so far from South Central, the community was on edge just like when the Black Lives Matter protests happened, yet no one boarded up their storefronts and owners didn’t take to the rooftops with guns like they did in Koreatown. All was quiet on the Waterfront, so to speak, except that on the second night there was a major fire that broke out at the corner of 22nd Street and Pacific Ave. where Frank Acetta had started to build a motel. It wasn’t even half built and by the time I arrived on the scene it was entirely engulfed in flames.

By the looks of things the LA Riots had arrived in San Pedro and as I stopped to investigate the scene I was approached by an undercover cop who I knew from Ante’s. He seemed worried and then admonished me to be careful. He opened up the trunk of his unmarked car and pulled out a revolver and said, “Jimmy you might need one of these tonight.” He placed it on the fender and I looked at him, paused and said, “The fewer of these on the street tonight the better off we’ll all be.”

“Oh well that’s your call,” he said. It was later discovered the motel fire was lit on purpose to collect the insurance and was completely unrelated to the riots, but only used it as cover.

Now there’s several things that I learned from this, the motel that was destroyed 30 years ago but still hasn’t been built and has laid fallow all these years and is only now being considered for a development — that’s three decades of failure to build housing. Second, it was estimated that at the peak of the LA uprising that there were some 30,000 people involved in the riots. During the five days of unrest, there were more than 50 riot-related deaths — including 10 people who were shot and killed by LAPD officers and National Guardsmen. More than 2,000 people were injured, and nearly 6,000 alleged looters and arsonists were arrested.

By contrast this is less than .01% of the total population of this great city that on this particular date chose to break the law which means that the other 99.9% of the population are comparatively law abiding citizens and yet are many times targeted even still in the same ways as Rodney King was. My conclusion is that we can’t ever hire enough police to put down an outbreak of violence where even .01% of our neighbors break the law at any given time and that our collective public safety relies more upon certain intangibles like cooperation and a justice system that is equitable.

(James Preston Allen, founding publisher of the Los Angeles Harbor Areas Leading Independent Newspaper 1979- to present, is a journalist, visionary, artist and activist. Over the years Allen has championed many causes through his newspaper using his wit, common sense writing and community organizing to challenge some of the most entrenched political adversaries, powerful government agencies and corporations.)