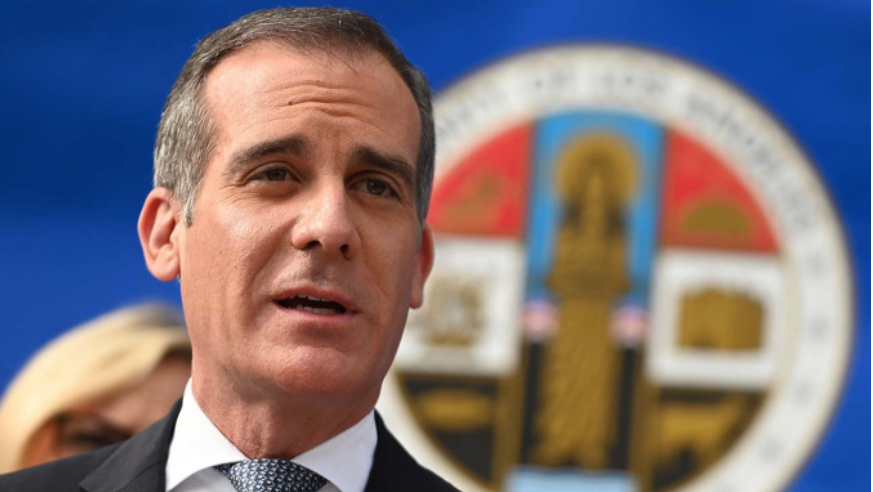

CommentsPresident Joe Biden has nominated Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti as ambassador to India.

Assuming the Senate confirms him, Garcetti, who would leave office early (his second term ends in December 2022), might find India familiar in certain respects. Like Mumbai or Delhi, Los Angeles now has massive homeless encampments throughout the city, even increasingly in posh neighborhoods like Brentwood and throughout the middle-class strongholds of the San Fernando Valley. Late last week, as Garcetti prepared to leave town, homeless advocates, angered by a city ordinance against indiscriminate camping on city streets, vandalized Getty House, the mayor’s official residence.

It’s not the scenario Garcetti would have wanted at the end of his tenure. The son of a former L.A. district attorney, a graduate of Columbia University, and former Rhodes scholar, Garcetti once seemed, to the city’s media establishment, like the epitome of a modern progressive mayor. In 2018, USC’s Dornsife Magazine embraced the idea that the city was undergoing a “renaissance” built around density, verticality, and transit—all components of Garcetti’s vision. Garcetti won reelection in 2017 in a low-turnout race, getting more than 80 percent of the vote against virtually nonexistent opposition. Some (notably Garcetti himself) even saw him as a potential president, but that notion didn’t test well, and Garcetti took the same express to national oblivion as New York’s Bill de Blasio.

Go past the hype, and you find at best a lackluster record. Garcetti leaves a legacy that the Los Angeles Times charitably referred to as “unfinished business.” Though he pledged in his annual state of the city address to focus on homelessness and “social justice,” he has done little to achieve either. “He has broad concepts,” suggests Jill Stewart, former editor of L.A. Weekly, “but fails to come through and do it.”

In New York, de Blasio represented a clear break from the past, but in Los Angeles Garcetti’s politics reflected those of his predecessors, Antonio Villaraigosa and James Hahn. All are creatures of L.A.’s union-dominated political culture and worked closely with developers seeking—often against public opposition—to densify and gentrify the city. Garcetti seemed even more determined than his predecessors not to offend powerful interests. He was particularly close to the real-estate speculators who sought to benefit from his fashionable commitment to density. A federal grand jury has indicted former city councilman Jose Huizar, another key ally of real-estate developers, for bribe-taking. Others further down the city pecking order also face charges of taking bribes to back big new projects, including ones that violated zoning ordinances.

Even before the pandemic, conditions in L.A. were in decline. The crux of the problem lies at the juncture of expensive housing and low wages. For most of the past decade, Los Angeles has had some of the highest poverty rates for major U.S. metros, as well as the highest rates of overcrowding. Almost 500,000 households in the L.A. metro area live in “crowded” conditions, defined as having more than one person per room. Of the 1 percent most-crowded census tracts in the U.S., more than half are located in L.A. and Orange Counties; yet amazingly, L.A. has 120,000 vacant units.

The city no longer produces many good new jobs. According to research by Chapman University’s Marshall Toplansky, the vast majority of L.A. jobs paid below the median annual income, many under $40,000. Before 1990, L.A. was a capitalist dynamo and haven for middle-class jobs, the global center for aerospace, home to the nation’s largest manufacturing economy, an energy powerhouse, and the center of a vast construction industry. Now all the big aerospace companies have moved their headquarters out. Only upstart SpaceX, in nearby Hawthorne, remains, though Elon Musk, who moved to Texas last year, seems intent on moving much of his operation to the Lone Star State. All the big oil companies and banks have either merged, shrunk, or moved away. When CBRE moved to Dallas last year, L.A.’s downtown lost its last Fortune 500 company.

LA’s signature industry, entertainment, is, along with the devastated hospitality sector, key to any economic recovery. But Hollywood is losing its reach, as evidenced by the declining Oscars audience, and both entertainment and hospitality suffered under L.A. County’s tough lockdowns, which cost an estimated 50,000 jobs locally—by far the biggest loss of any region. Meantime, the center of gravity has shifted toward streaming services like Disney, Netflix, and Amazon; of those three, Disney, the only one rooted in Los Angeles, has just announced that it is moving 2,000 management jobs to the Lake Nonacommunity in Orlando, Florida. Tyler Perry, among the most creative minds in Hollywood, has constructed his own giant facility in Atlanta.

L.A. fared comparatively well during the pandemic, suffering a far lower fatality rate than major eastern cities—but its unemployment rate is the highest among the nation’s ten largest cities, and it is laboring through one of the slowest job recoveries. Violent crime, which had long been in decline, has revived. By some measurements, L.A. is now home to the three most unsafe neighborhoods in the United States.

It would be unfair to blame Garcetti entirely for L.A.’s current predicament. He may mouth progressive slogans, but he’s no wrecking ball like de Blasio. Rather, he’s a cautious politician—often to a fault. “He doesn’t use his political capital at all,” notes L.A. journalist Jerry Sullivan, who has covered downtown in a decades-long career for various publications and now writes the widely read SullivanSaysSoCal report. “He doesn’t take on things that would upset the power brokers and developers.”

Garcetti has failed utterly to address the city’s omnipresent homeless encampments, a condition that businesses now rank as an even bigger problem than taxes, regulation, or crime. Los Angeles has the country’s largest homeless population, and it’s growing. The most recent annual count by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority tallied 66,433 unhoused people countywide and 41,290 people in the city.

Garcetti’s attempts to deal with the issue, including the passage in 2016 of a $1.2 billion bond measure, notes Sullivan, have been ineffective and plagued by corruption, poor planning, and runaway costs. Some projects have cost $1,000 per square foot to build; a small apartment at those prices would easily break the $600,000 price. “Money was given to fix the problem,” says Sullivan, “but much was misappropriated or stolen.”

The scourge of homelessness and unaffordability is a major issue in particular for small businesses. Big-city developers may have liked doing business with Garcetti and Huizar, but most small-business owners were less impressed. More than half of L.A. County businesses, according to a Los Angeles County Business Federation poll, call L.A. the least business-friendly city in the region; barely 7 percent consider it the most friendly.

“He may go to India, but we are still here,” says Tracy Hernandez, president of the 400,000-member strong federation, who praises the mayor on some measures, like including women in key positions. “He leaves behind worse housing unaffordability and homelessness than when he got here.”

Homelessness is just the tip of the iceberg of L.A.’s ever-widening class divide. The city continues to attract the ultra-rich; a new report by data firm Wealth-X suggests that L.A. trails only New York as a home for people with net worth above $30 million. These people dominate the luxury condo market, three-quarters of which, according to one study, have absentee owners, are second homes, or stand empty. Not surprisingly, according to real-estate consultancy Costar, rents have dropped sharply downtown and in the central core, particularly for luxury housing. Desperate landlords are offering dramatically lower prices to bring in wary buyers and renters.

Clearly, the downtown-focused densification strategy has not been an unqualified success. It seemed to work when it unleashed a torrent of real-estate speculation, much of it fueled from abroad. But the market never grew as expected, and in the interim many of the businesses that once thrived downtown—garment firms, jewelry businesses, low-end retail shops—were forced out. And the state and county pandemic lockdowns devastated their in-person shops that had predominated in what was once a hotbed of immigrant commerce.

Taking a walk around downtown Los Angeles or Garcetti’s old district in Hollywood, one can see what such speculation has done. In the place of a thriving, blue-collar, largely immigrant economy, one sees many luxury buildings with vacancies, often surrounded by homeless encampments. The large buildings that once housed the now-defunct American Apparel, which employed more than 2,500 workers, are empty, surrounded by what Sullivan calls “a dead mall” of hip restaurants and shops. Estimates of vacancies for rental units range from almost 20 percent to 30 percent or more, and most of the luxury condominiums, both downtown and around the city, are close to half-owned by speculators and institutional investors. The investors who spurred the real estate inflation now seem to be looking to leave their luxury developments behind. Indeed, rumors recently surfaced that the massive three-high-rise Oceanwide Plaza project near Staples Center is up for sale, at bargain prices.

The drive to densify working-class areas like East L.A. and the Southside also elicited powerful, occasionally violent, grassroots opposition. The Garcetti-approved 35-story Cumulus tower in South L.A., for instance, doesn’t appeal much to locals. Activist Damien Goodmon, who unsuccessfully challenged the project in 2016, calls apartment prices of $5,292 per month or more “Beverly Hills prices in South L.A.”

Garcetti’s fixation on density and transit also sparked opposition in middle-class areas and among local small businesses. Many were put off by Garcetti’s notion of “road diets” (removing parking and lanes of traffic) for a city with worst-in-the-country traffic. Garcetti pushed this approach as a solution to L.A.’s monumental traffic issues, yet it had no real impact, in part because roads in California are also among the worst in the country. Meantime, mass transit, despite some $20 billion in investment, actually lost market share and riders, even before the pandemic.

Once described as “the city that grew,” L.A. is now the city that stagnates. Rising outmigration is a key problem. Over the past decade, Los Angeles County lost 745,000 net domestic migrants, a rate matched only by New York City and its surrounding region.

Among those leaving, or not coming, are minorities. Los Angeles was once a mecca for African-Americans, but new research by the Urban Reform Instituteshows a shrinking black population and cost-adjusted incomes roughly 40 percent lower than in places like Atlanta. Hispanic growth, which underpinned city demographics in the last few decades, is also dropping off; for all minorities, L.A. offers lower incomes and a lower chance of homeownership than many locales in the South, Sunbelt, Midwest, or Great Plains.

Even the foreign-born are trending away. Along with New York, L.A. was once the premier immigration hub; now a lack of good jobs and affordable housing is discouraging new arrivals. A new study from Heartland Forward shows that Los Angeles and its surrounding area lost foreign-born people in the past decade, even as their numbers swelled in key competitor cities like Dallas-Ft. Worth, Phoenix, and Las Vegas.

Perhaps the best word to describe L.A. after Garcetti would be “rudderless.” The days when business leaders worked closely with politicians and unions—hallmarks of Tom Bradley’s early, highly successful mayoralty—are mostly over. After a struggle with the last generation of committed business leaders, including the late Eli Broad, the Los Angeles Unified School district has continued to deteriorate, adding political indoctrination to its weak academic performance.

It’s possible that Garcetti’s signature success—snagging the 2028 Olympics—could help pace a revival, particularly if the city repeats its brilliant execution of the 1984 Games. But a successful sequel seems unlikely, given a far less engaged business community, greater poverty, and crumbling infrastructure. In contrast with 1984 Los Angeles, today’s city lacks strong business leadership to direct such a project, leaving it to the tender mercies of progressive administrators and planners.

No outstanding candidates to succeed Garcetti have emerged so far, and most of the leading figures come from the progressive ranks of the city council. Whoever takes up the reins will face a choice: change course or accelerate the city’s decline. The recent ordinance to limit homeless encampments demonstrates something of a rebellion among L.A. voters. Hope abounds that a moderate, pro-business candidate, like developer Rick Caruso, might emerge, but as long-time conservative commentator Joel Fox admits, “there’s no Richard Riordan on the horizon.”

Yet despite the bleak politics, the situation is far from hopeless. Los Angeles still has great weather, mountains, beaches, top universities, Hollywood, the nation’s largest port complex, and many still-livable neighborhoods. The city has come a long way in the past century, from an obscure cow town retreat to the nation’s cultural capital, aerospace center, and entrepôt.

Eric Garcetti did little to strengthen these assets and diminished some of them, but Los Angeles has survived mediocrity and weak leadership before. It has also endured riots, earthquakes, fires, droughts, and floods. A great city can transcend the mistakes of its political class, but it would certainly be helpful if Los Angeles could find—and soon—leaders with vision to match the city’s potential.

(Joel Kotkin is a fellow at Chapman University and the executive director of the Urban Reform Institute.)