CommentsGet ready for whiplash: After receiving $1.3 billion in new money from lawmakers this year, the University of California now wants to raise tuition on each incoming undergraduate class. Every year. Indefinitely.

Once tuition spikes for an incoming class, it would stay flat for six years for that class — allowing students to more reliably calculate the multi-year cost of a degree.

The UC Board of Regents will vote Thursday on a tuition-hike plan two years in the works that was initially derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic but has since been resuscitated.

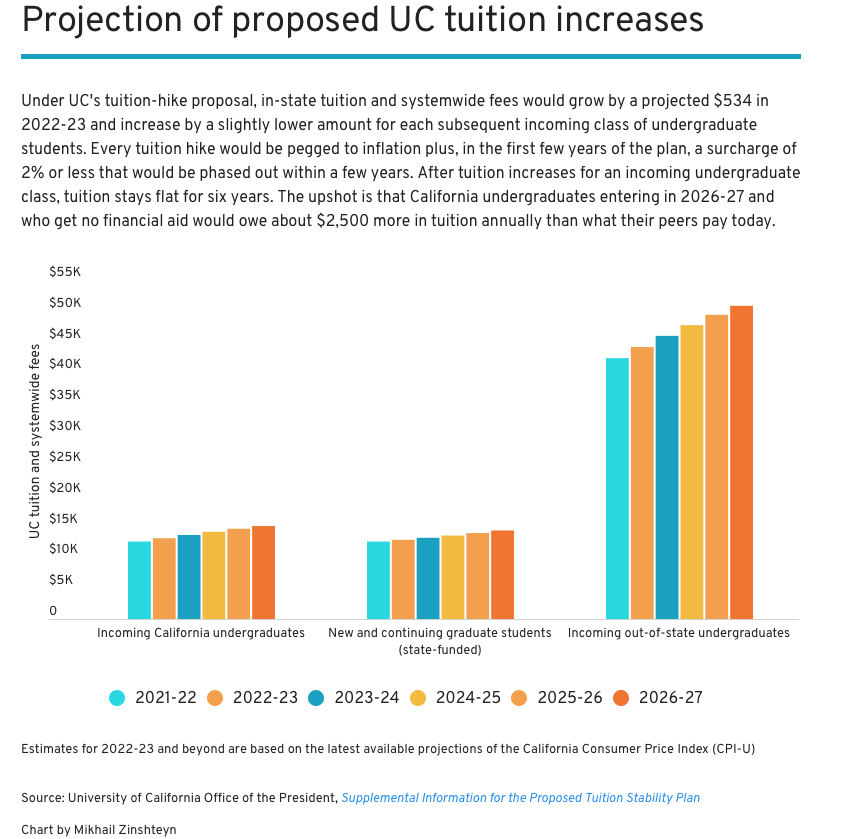

UC officials project that in-state tuition and systemwide fees would grow by $534 in 2022-23 and increase by a slightly lower amount for each subsequent incoming class of undergraduate students.

The upshot is that in 2026-27, California undergraduates entering the UC would owe a projected $15,078 in annual tuition and statewide fees — about $2,500 more than what in-state undergraduates pay now.

The proposal is a complicated one, stippled with tuition hike estimates pegged to inflation and studded with various exemptions meant to cap what students would ultimately owe. But what’s definite is that this marks a dramatic departure for the UC: After doubling tuition during the great recession in response to deep state cuts, the UC raised tuition just once since 2011.

“I do believe (the tuition increase is) likely to pass even though I would not like it to,” said Alexis Atsilvsgi Zaragoza, a UC Berkeley undergraduate and a student voting member of the Regents who’ll be casting her first vote at this week’s meeting.

Her dissent has powerful allies. Speaker of the Assembly Anthony Rendon, a Long Beach Democrat, and Senate President pro Tempore Toni G. Atkins, the two leaders of the Legislature, oppose the tuition increases at this time, they told CalMatters in emails.

“Families have been struggling during this pandemic and this year has been difficult enough for so many Californians,” said Atkins, a San Diego Democrat.

UC President Michael V. Drake declined to be interviewed for this story. At the May Regents meeting Drake said the tuition plan will “help campuses preserve academic excellence and critical support services.

“It’s no secret that UC’s funding has been unstable for years.”

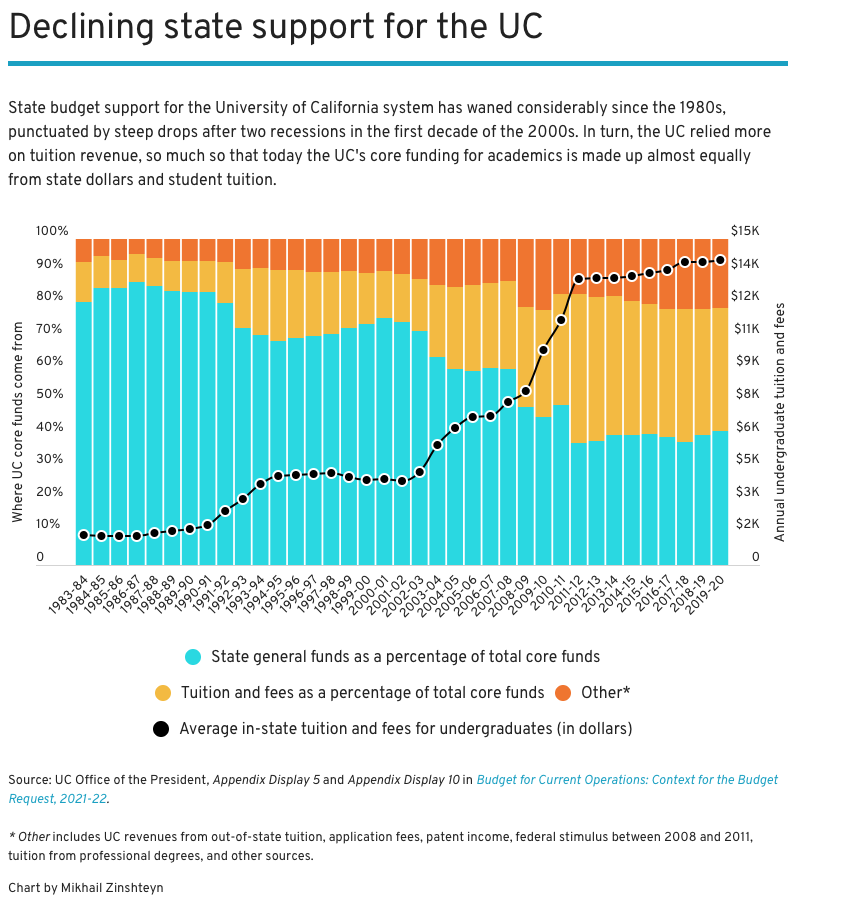

His office argues that the UC needs stable revenue from tuition to counter the long trend of state disinvestment. The system four decades ago got about 80% of funding to educate students from state support. Today that share has shrunk to closer to 40%, nearly identical to how much revenue the system collects from tuition. This year’s massive infusion of state cash to the UC does little to reverse that trend.

The UC president’s office projects soaring costs totaling $2.1 billion by 2026-27 on top of current expenses, a shortfall it argues must be plugged with tuition hikes along with more money from the Legislature. The new added revenue would pay for more faculty hires, salary and benefits increases, plus a slew of student support services and programs aiming to boost graduation rates.

And the UC maintains that the proposed tuition model is ultimately better for all students.

Low-income students who don’t pay tuition anyway because they qualify for financial aid would get even more money for books, housing and food, because about 36% of the revenues from the tuition hikes would go back to student aid.

And with tuition growing only once per graduating class and tied to inflation, the cost of attendance will be predictable and stable for higher-income students who’ll pay full freight.

Specifics of the proposed tuition hike

The proposed plan would increase tuition for each new incoming undergraduate class of students starting in 2022-23. Every tuition hike would be pegged to inflation. Undergraduate students also would pay a surcharge of 2% or less, which would be phased out within a few years.

New and continuing students in state-funded graduate programs would see a different kind of tuition hike: theirs would be annual, rather than occurring once for every incoming class, and grow with inflation starting in 2022-23.

The proposal ties tuition growth to a three-year rolling average of inflation. Doing so keeps tuition from changing drastically if consumer prices soar.

The proposed hike would cap tuition growth in any year at 6%. Another provision would grow tuition by a smaller amount if state lawmakers increase their share of UC’s budget by more than 5%. But that kind of increase is rare: UC’s state support has grown by less than 4.6% per year after hitting 5% in 2014-15.

Zaragoza, the student Regent, says a cap of 6% is still too high; she’ll push for a lower threshold. She wants trigger language in the Regents’ proposal that would force the UC to pause tuition hikes in extreme cases like, say, a global pandemic. And she’d like the Regents to be required to renew the plan regularly — at least once a decade.

“We’re using the messaging of a ‘forever hike,’” said Josh Lewis, a rising senior at Berkeley and chair of government relations for the UC Student Association. The systemwide student group opposes any tuition increase and is organizing a phalanx of students to protest the proposed hikes at this week’s Regents meeting. The association is also submitting commentary pieces in all UC campus student papers and has met with Regents.

Lewis said he wants the state to boost its support to the UC in lieu of tuition hikes.

And the regents themselves aren’t unified in support. Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis, who serves as a regent, tweeted her opposition while noting how the cost of tuition to UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business has skyrocketed since she attended in the 1990s.

But at least one influential lawmaker is comfortable with the UC plan. Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, a Sacramento Democrat who chairs the budget subcommittee on education, said at a February hearing that “moderate and predictable” tuition increases of the kind the Regents are considering do “make sense.”

There’s at least one kink in the UC’s revenue-boosting arguments. California law gives the governor’s director of finance the power to reduce the state funds headed to the UC (and California State University) if the university raises tuition. That’s because every increase to tuition means the state budget spends more on the Cal Grant, the state’s main student aid grant — something a third of UC undergraduates get, and which is automatically pegged to what the UC charges for tuition.

Most students won’t actually pay

Currently 56% of California undergraduates at the UC don’t pay any tuition due to a combination of state, federal and university aid.

That’s not changing under the proposed UC tuition model. The UC calculates that students who aren’t in wealthier households will ultimately owe less in overall college costs under this increase than if tuition stayed flat. That paradox is due to the fact that the UC plans to spend more than a third of the increased tuition revenue on student financial aid. That money plus state and federal grants translate into savings of nearly $2,000 a year by 2028-29 for students whose parents earn $120,000 or less.

Despite all that financial aid, students in dire need still fall through the cracks. There are students living out of cars and vans. A 2020 UC report found that 6% of undergraduates who get federal grant aid still experience homelessness.

For families with incomes of $150,000, UC’s tuition increase plan would result in added tuition costs, growing to about $2,000 by 2028-29 for undergraduates. Those costs will grow even more for wealthier families who don’t qualify for the state’s middle-class scholarship.

The proposed tuition hike is basically “a progressive tax,” said UC Regent Cecilia Estolano, now the body’s chair, who said she was undecided on the proposal at the May meeting.

“You’re going to charge more affluent people a bit more, but you’re going to give them a promise in exchange: Everybody will have the faculty and staff ratio that they expect out of the University of California.”

Mikhail Zinshteyn has been a higher education reporter since 2015. As a freelancer, he contributed to The Atlantic, The Hechinger Report, Inside Higher Ed and The 74. Previously, he was a reporter at EdSource and before that a program manager at the Education Writers Association. Mikhail was born in the Soviet Union and has a master's degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics. He is based in Los Angeles. Pell grants and work-study helped pay for his undergraduate degree at Union College.