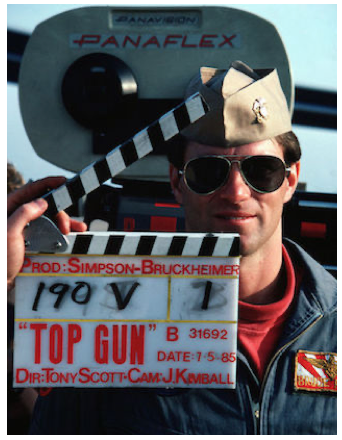

CommentsCONNECTING CALIFORNIA-Bring back Topgun! By that, I do not mean Top Gun, the cliché-ridden, late-Cold War Tom Cruise film about speed-crazy Naval fighter pilots that still defines San Diego in the public imagination.

The movie “Top Gun” never really left us and is already on its way back with a sequel scheduled to crash-land in theaters next year.

No, what California really needs back is Topgun, the U.S. Navy’s graduate school for elite fighter pilots that inspired the movie. For nearly 30 years, Topgun thrived in San Diego -- before it was moved to the Nevada desert, as part of the military consolidation of the 1990s. Its departure still burns. Topgun was a human-centered institution that closely studied the many failures of naval aviation in order to train better pilots. As such, Topgun represents the road not taken by a California that grows ever more obsessed with attaining technological superiority and celebrating successful inventions, and too often ignores the difficult work of teaching people how to cope with technology’s inevitable failures.

While the film “Top Gun” portrayed Topgun as an intramural pilots’ tournament full of egomaniacs and guys who famously “felt the need, the need for speed,” the actual Topgun has long embodied a sober, resilient, and strikingly democratic theory of excellence. It is precisely this spirit that California so desperately needs now.

From its earliest days, Topgun has prided itself on being counter-cultural, like California itself. While the military is rank-obsessed, Topgun was led from the beginning by junior officers, on the theory that younger pilots will see new possibilities and will innovate. While it’s part of a Defense Department famous for over-spending, Topgun was started on the cheap in a discarded trailer with stolen furniture. And in an era of automation and simulation and failsafe systems, Topgun was built on the notion that the human in the cockpit comes first, and that pilots don’t need new tech toys but rather loads of live practice learning how to fly their flawed planes.

“We live today in times of great uncertainty with problems that seem unsolvable,” writes Topgun founder, Dan Pedersen, in a terrific new memoir, Topgun: An American Story. “Topgun is a reminder that things can be changed.”

As Pedersen describes it, Topgun, launched at Naval Air Station Miramar in just 60 days in 1968, was an insurgency within the military that responded to large numbers of deaths and plane losses during the Vietnam War. Pedersen and other young officers who founded the school believed that the U.S. was losing in Vietnam because it had too many rules and regulations for its pilots, and too much faith in technology. “We brought our expensive high tech into this knife fight in a phone booth,” Pedersen writes of Vietnam.

Topgun represents the road not taken by a California that grows ever more obsessed with attaining technological superiority and celebrating successful inventions, and too often ignores the difficult work of teaching people how to cope with technology’s inevitable failures.

These junior officers launched Topgun to try new approaches. They succeeded. The school changed the ways pilots fired their missiles against their enemy, and they developed brand-new tactics for flying the F-4 Phantom, so that it could better compete with North Vietnamese MiGs. Topgun has been pioneering new techniques ever since.

Perhaps the most important part of the school was how it transformed the culture of naval flying, rather than just training a few guys. “It was about flying and ideas. Topgun was best understood as a graduate school. It functioned essentially like a teachers’ college for fighter pilots,” writes Pedersen. “Our job was not just to teach pilots to be the hottest sticks in the sky. It was to teach pilots to teach other pilots to be hottest sticks in the sky.”

In this way, Topgun seeded the Navy and the U.S. military with new ideas about flying. By the 1980s, their ideas had spread worldwide, as Topgun ran roadshows for troops, sent detachments to the Philippines, Japan, and Saudi Arabia, and formed a mobile training team to visit NATO allies. British fighter pilots were regulars at Miramar (though they partied too hard for their American hosts to keep up).

The movie, which arrived in 1986, was not particularly realistic (despite some assistance from Topgun officials, who made one durable suggestion -- turning Tom Cruise’s love interest from an aerobics instructor into a brainy tactical consultant modeled on a real-life military mathematician.) But the movie made Topgun world-famous, and applications and foreign visits soared. Unfortunately, it also sparked jealousy from other parts of the military.

“There were unintended consequences within naval aviation that affected Topgun for years to come,” writes Pedersen. “The other communities. . .felt slighted by the movie. It stirred old resentments and as the 1980s came to a close, the school faced another series of bureaucratic assaults that I believed were designed to cripple it.” Those attacks included efforts to eliminate Topgun’s status as its own separate command and even to take away its name.

“There were unintended consequences within naval aviation that affected Topgun for years to come,” writes Pedersen. “The other communities. . .felt slighted by the movie. It stirred old resentments and as the 1980s came to a close, the school faced another series of bureaucratic assaults that I believed were designed to cripple it.” Those attacks included efforts to eliminate Topgun’s status as its own separate command and even to take away its name.

Then, in the 1990s, with the defense budget cut and bases being consolidated, Topgun became an actual target. When the Miramar Naval Air Station was handed over to the Marines, who had themselves been pushed out of El Toro and Tustin in Orange County, Topgun lost its home and was relocated to Fallon, Nevada, where it became part of the United States Navy Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor program. As trucks pulled out of Miramar for the move to the Nevada desert in 1996, people lined the San Diego-area freeways to say goodbye.

Pedersen praises more recent generations of Topgun commanders for keeping its spirit alive, but he is full of warnings about how the military’s devotion to expensive new technologies steals money and attention from essential training. He laments the 2006 decision, driven by then-Vice President Dick Cheney, to kill off the F-14 Tomcat, a versatile and reliable plane (it’s what Cruise flies in the film), in favor of expensive and ineffective stealth fighters.

“Our country has been put at risk by the Pentagon’s fascination with stealth technology,” he writes. “We worship at high technology’s altar and are on the verge of selling our souls.” Pedersen adds ruefully that the F-14 is still being flown by the military of one country -- Iran.

What’s been lost in our love of technology is the emphasis on the human, and the importance of failure, time, and practice. “The basic truth of fighter combat remains the same. It is not the aircraft that wins a fight, it’s the man in the cockpit,” he writes. More importantly, Topgun is about a hard-earned wisdom: fighter planes, like other products made by humans, eventually fail, and pilots must be trained extensively to manage such failures.

In a hostile and competitive world, is there any skill more important than knowing how to fail -- and keep on fighting?

(Joe Mathews writes the Connecting California column for Zócalo Public Square.) Top photo: Wikimedia Commons/National Archives and Records Administration; Tom Cruise photo: Wikimedia Commons. Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.