CommentsONE MAN’S OPINION-Perhaps, we should start calling Jefferson “Tommy.” He was only 33 years old when he started on his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. Because one does not start at the top, Tommy already had gained the respect of other thinkers of his day. The use of the name Tommy could serve to highlight that hard work, youth and intelligence may coincide, albeit not always.

Pogo, born in 1941, was only 29 old April 22, 1970 when he made his famous Earth Day statement, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Compared to Tommy and Pogo, Marty at 45 was an old man when he published I and Thou in 1923. He lived to be 87, Tommy lived to 83, but Pogo died young at 52. Each, however, carried the same timeless message.

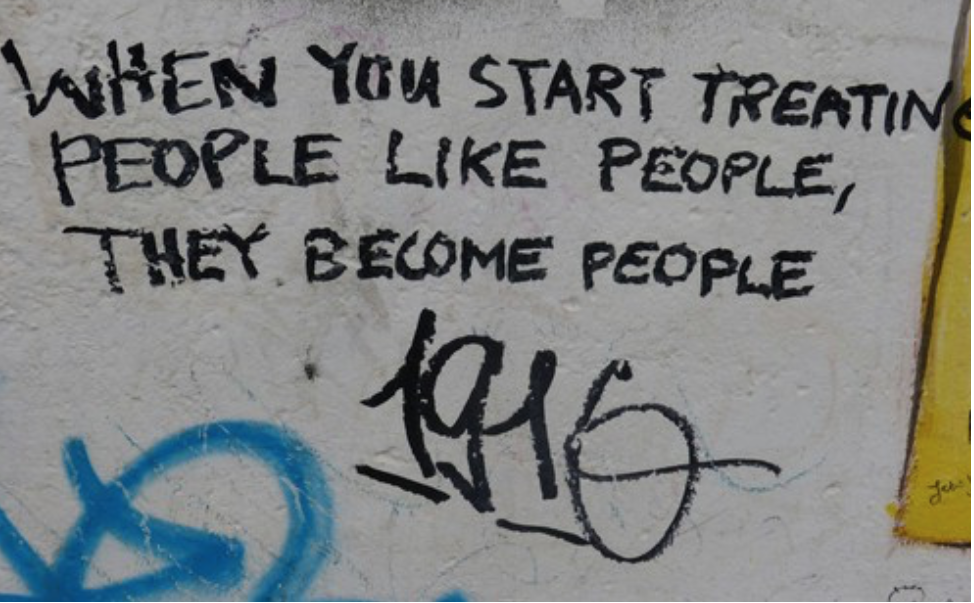

Encountering the Core Being of Others Is the Basis for A Good Life

Adam Kirsch’s April 29, 2019 article in The New Yorker Magazine, “Modernity, Faith, and Martin Buber,” reminds us that Americans of all ages and backgrounds have access to the same philosophy to lead us away from our collective descent into irrationality. We can rise above the tendency to treat fellow human beings like inanimate objects.

Pogo’s admonition is crucial to remember when people are pointing their fingers at everyone else, while blissfully unaware than they themselves are committing a similar sin, mistake or foolishness. People who live in fear find vague ambiguities intolerable. Emotional memes are treated as immutable truths. Marty is an antidote for our longing for a certainty without regard to its validity. The genius and/or the problem with Buber, for me at least, has been that I never was sure what he was saying except that one should attempt a genuine encounter with others.

That is what Tommy was saying with the Declaration’s “all men have inalienable rights” including life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. How can I treat another as if he or she were a Thing, while claiming inalienable rights for myself? Surely, if I relegate another person to some label such as White, Black, Gay or Jewish, I am not encountering his or her core. Rather, I have made the other into the representative of an Intangible Thing – a group of people.

As Pogo might ask, “If I reduce another to a thing, should I not likewise treat myself as thing?”

The Virtue of Vague Ambiguity

Buber is important for another reason. After reading I and Thou, one finds ambiguity but with a sense that something elusively profound has been said. It is up to the individual to have his own I versus Thou encounter with the world. Dealing with the mystery, confusion and doubt is an affirmation of our humanity. Dogmatic certainty seems antithetical to morality.

Tommy and his buddies created a political framework where each person’s individuality afforded him the freedom to encounter life with never-ending I versus Thou experiences. Is that not what MLK meant by “judge a man by his character and not by the color of his skin?” One cannot lock children in cages away from their parents when one lives I and Thou. One cannot promote inter-group rivalries, hatred and violence without negating I and Thou.

While one may never be certain what the I and Thou is at any particular moment, it seems to entail acceptance of each person as if he were “I.” Or, maybe it means acknowledging, “But for the grace of G-d go I.” Is a person who engages in behavior which angers me a “non-person”? An “it”? What if my life had turned another corner or had I overheard a careless whisper, who would I be today?

Perhaps Marty, Pogo and Tommy show us that dealing with other people without placing some “it” label on them is the basis of Truth, Justice and the American way. But will we all collectively make it the American way?

(Richard Lee Abrams is a Los Angeles attorney and a CityWatch contributor. He can be reached at: [email protected]. Abrams views are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CityWatch.) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.