CommentsMUST READ-In recent decades, I have been one of those celebrating the power of urbanism: the capacity of cities and towns to create economic dynamism, expanded life choices, opportunities for active living, and healthier, more resource-efficient lifestyles.

This power is perhaps most obvious in the dense cores of cities, where people interact with each over across a wide spectrum of private and public spaces that are all connected to that ultimate public space system, the street.

In that celebration I have joined people like Edward Glaeser (author of Triumph of the City) and Richard Florida (author of The Creative Class). In their own works they have described cities as powerful engines of creative social and economic development. They and others acknowledge a debt to the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who championed the humble sidewalk as an arena of human interaction, occasionally producing exchanges of information and “knowledge spillovers” that are surprisingly important for economic as well as social development. “Lowly, unpurposeful and random as they may appear,” said Jacobs, “sidewalk contacts are the small change from which a city's wealth of public life may grow.” We are learning that other kinds of wealth also grow from the network of seemingly-modest interactions in the city’s public spaces.

But along the way to this very necessary “re-urbanism,” it seems that things have gotten terribly out of balance. The story is distressingly similar in many cities around the world. Newly popular city cores are drawing more people, pushing up prices, and driving out small businesses and lower-income residents. City leaders, alarmed at the trends, try to build their way out of the problems, on the theory that more supply will better match demand, and result in lower rents and home prices. But the efforts don’t seem to work— and even seem to exacerbate the problems.

That’s because cities aren’t simple machines, in which we can plug in one thing (say, a higher quantity of housing units) and automatically get out something else (say, lower housing costs). We can’t just “build, baby build” and solve our problems of affordability. Instead, cities are “dynamical systems,” prone to unintended consequences and unexpected feedback effects. By building more units, we might create “induced demand,” meaning that more people are attracted to move to our city from other places – and housing prices don’t go down, they go up.

Unfortunately, we have been treating cities too much like machines, but for an understandable reason. In an industrial age, that has been a profitable approach for many at the top, and over the last half century, it seemed to fuel the middle class too. More recently, we have begun to see very destructive results—creating lopsided cities of winners and losers, and large areas of urban (and rural) decline. Even government programs meant to address the problems have seemed at times like a game of “whack-a-mole”—say, building some social housing in one place, and seeing more affordability problems pop up in another.

In the years after World War II, and especially in the United States, the largest areas of decline were often in the inner cities, leaving the “losers” of the economy behind, while the “winners” (often wealthier whites) fled to the suburbs. But more recently it has been the cores of large cities that have become newly prosperous, attracting the winners of the “knowledge economy”— and displacing the former long-time residents.

Meanwhile, the inner-tier suburban belts and the smaller cities and towns have suffered marked decline, resulting in predictable political backlashes, including the “populist revolt” of the so-called “white working class.” In the larger cities, lower-income and minority populations have been relegated to more peripheral suburban locations, with limited opportunities for economic (and human) development. This gap in opportunity means a gap in the lower-end “rungs of the ladder” that are so essential for immigrants and others to advance.

Like its Postwar counterpart of suburban growth, this more recent pattern of core gentrification and geographic inequality has also been an unintended result of conscious policies. This time we aimed to achieve not suburban expansion, but the urban benefits of knowledge-economy cities, and their capacities as creative engines of economic development. That is indeed a powerful force to harness. Clearly, however, we failed to recognize the need to temper this growth and maintain a just balance of opportunity.

Florida and Glaeser, to their credit, have both acknowledged some deep problems with their models. In a 2016 interview, Florida confessed, “I got wrong that the creative class could magically restore our cities ... I could not have anticipated among all this urban growth and revival there was a dark side to the urban creative revolution, a very deep dark side.” Glaeser also admitted, in a panel discussion with Florida in 2017, that recent years had seen a blowback from this re-urbanization, in the increasing segregation of winners and losers, and the political fallout that has resulted: “Let me agree that we are facing something of a crisis.”

Too much of a good thing?

The problem with the simple formula of densifying urban cores by concentrating the “creative class” can best be understood from the point of view of network theory, and especially, the theory of how people form economic networks in an urban setting. It’s possible to have too much of a good thing—to over-concentrate, and to rely too much on what are known in the theory as “rich club networks.” These are nodes of concentrated connection that are particularly well-connected, and that therefore offer access to concentrated resources—in this case, concentrations of talent and wealth. Just as in everyday life there is a great benefit to “who you know” and being on the inside of exclusive insider networks of knowledge, wealth and opportunity, “rich club networks” capitalize on similar concentrations of access within them. The trouble is, the benefits may not spill over to other areas outside of those networks.

As Luis Bettencourt of the University of Chicago points out, this network inequality can put a drag on the overall urban system, economically and socially. This is not only because of the costs in areas that are excluded, from problems like crime, policing, incarceration, social services and so on. It’s also a more basic effect of the dynamics of social networks, in what is known as “Metcalfe’s Law.” Networks—in cities or in other structures—benefit from the number of overall interconnected nodes, not just the advantages conferred by elite sub-clusters.

As Bettencourt put it, “the view of cities in terms of social networks emphasizes the primary role of expanding connectivity per person and of social inclusion in order for cities to realize their full socioeconomic potential. In fact, cities that for a variety of reasons (violence, segregation, lack of adequate transportation) remain only incipiently connected will typically underperform economically compared to better mixing cities,” he said. “What these results emphasize is the need for social integration in huge metropolitan areas over their largest scales, not only at the local level, such as neighborhoods.”

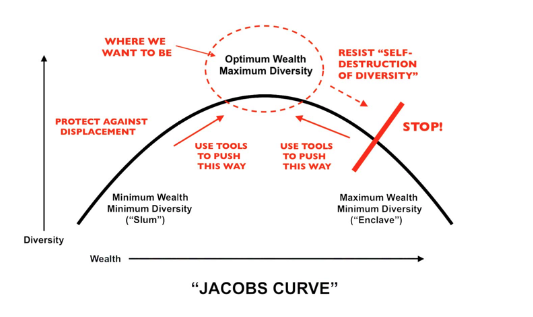

Put differently, urban equity and environmental justice are not just about fairness—they’re good for everyone’s bottom line. The goal of urban planning and policy, as Jane Jacobs pointed out, is to maintain an optimum of diversity, in incomes as well as other kinds—neither too many poor in one area, nor too many rich.

(Image by Michael Mehaffy.)

But the idea that we should concentrate at the top of the pyramid has its counterpart in supply-side economic theory, which holds that if you promote the interests of those at the top who are creating supply (by giving them tax incentives and other forms of stimulus) they will generate wealth that will “trickle down” to everyone else. George Bush Sr. famously criticized this idea as “voodoo economics”—and yet it became a dominant force in the world’s economic development after 1980, including urban development. We can see now from network theory what the problem is. It is not that the network phenomenon isn’t real, but that it can get out of control. Cities do generate powerful benefits from concentrations of talent—but also from “spreading it around,” and we need to strike a balance between the two approaches.

Perhaps the trouble with Glaeser’s triumphant city cores, and Florida’s creative class, was that they were too exclusive, too dependent on an isolated population of elite knowledge workers, and a limited secondary population that would mainly service their needs. We needed more than densification of cores with walkable, well-connected street grids and mixed use—as beneficial as those are; we needed a more “polycentric,” well-connected and diverse kind of city, geographically speaking too.

In many cities today, it seems, we are seeing the consequences of this “voodoo urbanism” play out. It was thought that if we just take care of the creative class, the universities, the technology industries and their knowledge workforces, then the output of all that urban critical mass, like some kind of economic nuclear reactor, will generate immense wealth that will trickle down to all. This idea is so pervasively seductive that it has been embraced by those who might otherwise resist supply-side economic theory (like the officials in my own home town of Portland, Oregon).

But once again we can turn to Jacobs for an early and prescient warning about the dangers of this approach. She warned against “money floods” which were no less destructive of good-quality and equitable urban development than “money droughts.” More fundamentally, she warned against “the self-destruction of diversity,” in any neighborhood that allows itself to tip over into monocultures of any kind—including monocultures of creatives, or Ph.D.s, or any other sort. Diversity of all kinds is an asset to be maintained, with careful tools and strategies—not only as a matter of social justice, but one of economic vitality too. Again, this is good for everyone’s bottom line.

This was Jacobs’ central argument: that the core task of city planning was to ensure the “generators of diversity:” of people and their numbers, of uses and activities, of pathways, of building ages and conditions—and of geographic locations. Instead of over-concentrating in the core, she suggested, we need a “polycentric” city, with lots of affordable pockets full of old as well as new buildings, and multiple opportunities waiting to be targeted. In such a region, economic growth—and likewise the demand for housing—can be tempered and modulated to remain more even and equitable. We do have tools available to do that: funding incentives, catalytic tools, taxes to dampen speculation, and many others.

At the same time, it seems more important than ever to provide good urban fabric in the suburbs too, where increasing percentages of the population live (including increasing numbers of the displaced poor). “Good urban fabric” means walkable, mixed, transit-served, with expanding opportunities in older as well as newer buildings. It means the same kind of geographic as well as other kinds of diversity, achieved through conscious strategic actions to dampen, incentivize, catalyze, and use other kinds of tools.

In place of voodoo urbanism, we might call this “Goldilocks urbanism”—curating an urban growth that is not too hot and not too cold, nor not too concentrated in any one place. The former approach has done an effective job of destroying historic fabric, raising prices, fueling gentrification, and leaving our cities less sustainable and less equitable. It has also done an effective job making some people very wealthy in a short period. But we continue to follow their simplistic formulas at our cities’ peril.

(Michael Mehaffy, Ph.D., is Senior Researcher at the Centre for the Future of Places at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and Executive Director of Sustasis Foundation in Portland, Oregon. This originally appeared in CNU.org Public Square.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.