CommentsBELL VIEW-Forty-three years ago, a gang of older kids jumped me on my way home from school.

They beat me up, pushed my face in the dirt, dragged me around by the collar of my shirt, and humiliated me in front of my friends. I can’t remember if there were three or four kids who jumped me. I can’t remember how many, or which, of my friends witnessed the attack. I can’t remember if it happened in the Spring, the Fall, or the Winter. I know where it happened because I took the same route home from school every day.

I have forgotten virtually everything about the incident. I have no witnesses to corroborate my story – first, because I can’t remember who was there, and, second, because I have little reason to doubt that the other witnesses (I count myself as a witness) can summon even a shadow of a memory of the event. Why do I believe that? Because nothing happened to any of them that day.

I’ll tell you what I can remember: I can remember the leader of the gang, let’s call him RT. I can remember him knocking me down, pushing my face in the dirt, dragging me around, spitting on me, laughing at me. I can remember RT because he became the star of 10,000 revenge fantasies I began spinning the second I picked myself up off the ground and wiped the dirt and spit from my face. I was small then, and weak. But not anymore.

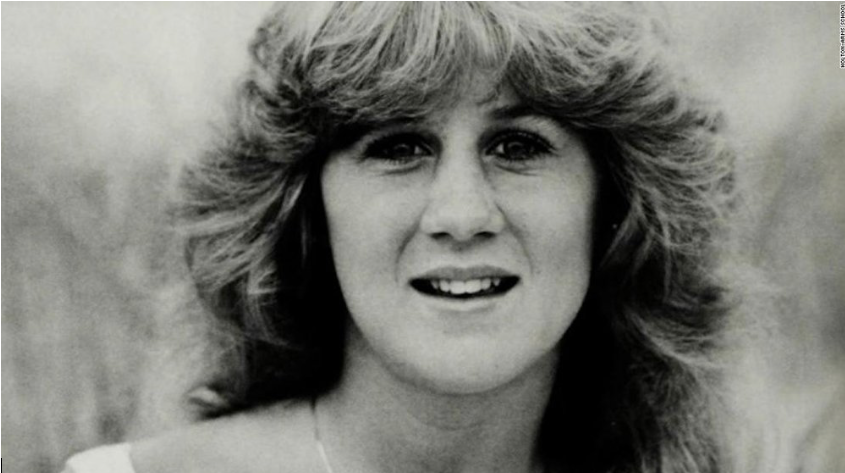

I remember RT all right. I remember him the way Christine Blasey-Ford remembers the guys who dragged her into a dark bedroom and laughed as they tried to rip her clothes off. I remember RT the same way Dr. Ford remembers the guy who held his hand over her mouth to stifle her cries for help, her screams of terror.

My ordeal was rough. My neighborhood was rough. RT and his buddies weren’t the only bullies I had to navigate around in my childhood. But the worst to happen to me was humiliation. Christine Blasey-Ford’s attack came right out of a horror movie.

I don’t need a scientist to tell me how Dr. Ford could remember her attacker with such certainty. I don’t need corroborating witnesses – witnesses who have no compelling reason to remember anything about the worst day in some other kid’s life – to back up Dr. Ford’s testimony. I believe her because I’m a human being, and I understand how memory works.

Criminal defense attorneys have devised ways to shed doubt upon this type of testimony – and maybe we’re leery of accepting uncorroborated accounts of vicious attacks because to do so would threaten the basis underlying the promise that we remain innocent until proven guilty. But hasn’t every one of us experienced some event that has burned itself into our memory? I’m not talking about early childhood – when the separation between fantasy and reality has not formed completely. I’m talking about an event from high school or middle school that you’ve relived a thousand times in your mind. Hasn’t everyone experienced something like that? And is it possible you could be mistaken about the identity of the kid who pulled your pants down, or dumped milk on your head, or made fun of your speech impediment in front of the whole class? Is it possible you forgot who did the one thing to you that you never really got over?

I don’t think it is possible.

The primary critique I have heard of Dr. Ford’s allegations are that they are supported by “no evidence.” But Dr. Ford’s testimony is evidence. California courts instruct juries that evidence may be direct or indirect. Direct evidence can prove a fact by itself. If a witness testifies she saw an airplane fly across the sky, that testimony is direct evidence that an airplane flew across the sky. Christine Blasey-Ford’s testimony that Mark Judge and Brett Kavanaugh shoved her into a room, held her down on a bed, tried to rip her clothes off, and that Brett Kavanaugh held his hand over her mouth to stifle her screams amounts to direct evidence that Mark Judge and Brett Kavanaugh attacked her. I submit the evidence is compelling, unrefuted by any credible countervailing evidence.

Is it possible I am mistaken about RT? Is it possible someone else – not RT -- beat me up, shoved my face in the dirt, laughed at me and spit on me in front of my friends that day? Someone who looked just like RT?

No. It is not possible. I knew RT at the time and I remember him. How certain am I? 100% certain. Any doubts? No. Not a shadow of a doubt. Does this make me some kind of memory genius? I don’t think so. That’s just how these kinds of memories work. Why do I think memories like this stick with us so well? Because we rehearse them over and over again as we plot our revenge or relive the humiliation. That’s how humiliation works – it embeds itself into our consciousness. The process in me – and I can only speak for me – was not a subconscious process. I consciously played with this memory over and over. It stayed alive because I never let go of it – like a movie I made inside my mind. Through the years, details dropped away – but the focus of my anger and resentment stayed because I would not let him leave.

Maybe I’m uniquely angry, but I doubt it. My experience feels universal, but, for some reason, we have forgotten how these kinds of memories persist, and we have allowed ourselves to be persuaded that – because a victim of a long-ago attack can’t remember the name of the street or the layout of the house or the names of the other people at the party – she can’t remember the identity of the person who attacked her. But that line of attack rings false for anyone who has not led a charmed life.

I have little doubt that RT has no memory of this event. I was just some kid he and his buddies beat up one day on their way home from school. I also doubt my friends remember the event. In fact, I hope they don’t. This event stayed with me so long because of the humiliation I felt. I’d taken a beating before, and since. But this one stuck. This one was part of a show. I hope my friends forgot all about it, and maybe the humiliation I felt existed more in my young mind than in theirs.

The humiliation also explains why I never told anyone. Why I never talked about it. Talking about it to anyone – including my parents – would only have prolonged the humiliation. I wanted it to disappear. But it would not disappear. My mind had a way of holding onto it, turning it over like my own private movie, creating alternative endings with me triumphant, my boot crushing RT’s face into the mud. I suspect many bullies instinctively realize this aspect of humiliation, and it explains why they perpetrate it. It extends their violence far into the future and magnifies the reach of their pathetic power.

This event did not ruin my life. I did not become an introvert or develop any life-long phobias. RT was not the only bully I – and others like me in my neighborhood, small, young, weak – had to deal with. I took the bus to and from school till RT and his buddies moved onto high school. Then I went back to walking to school with my friends. I don’t put this out here to join the ranks of victims – like Christine Blasey-Ford and the millions of other victims of sexual assault. I wasn’t in a dark room, alone. No one tried to rip my clothes off. I never thought I might be raped or killed. I write this only to demonstrate how memory works in the mind of a real human being. If you cannot understand this, I suggest you need to examine your own humanity before you comment on the experiences of others.

(David Bell is a writer, attorney, former president of the East Hollywood Neighborhood Council and writes for CityWatch.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.