CommentsNEW GEOGRAPHY--In the past, wrote historian Kevin Starr, California “was a final frontier: of geography and of expectation.” Today in the Trump era, California remains a frontier, but increasingly one that appeals largely to progressives. “California,” recently suggested progressive journalists Peter Leyden and Ruy Teixeira, “today provides a model for America as a whole.”

To them, California remains the “harbinger” of “new America” and “the most active front” in the battle to exterminate Trumpism. Yet this enthusiasm should be curbed somewhat by paying attention to what is actually happening on the ground here.

Economically, our state retains unquestioned areas of remarkable strength, notably in Silicon Valley as well as parts of coastal Southern California. But often overlooked are vast areas of underdevelopment, poverty and searing inequality, particularly in the interior. Overall, after a strong recovery from the recession, California’s GDP growth is now about the national average, well below that of prime competitors like Texas, Washington state, Ohio and even New York.

California as ideological avatar

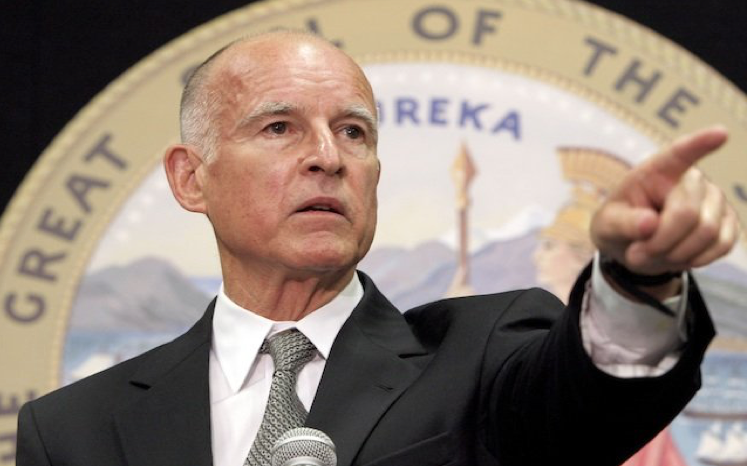

At the end of his long career, Jerry Brown has spent much time vamping in western Europe, Russia and China as the visionary leader of a de facto green nation-state. Yet it is rarely noticed that California’s greenhouse gas emissions are not dropping more rapidly than most places. In fact, according to the Energy Information Agency, the state since 2007 has reduced emissions by 10 percent, below the national average of 12 percent, meaning the state ranks a measly 35th in reduction.

Immigration and diversity is another defining aspect of the California model. This will be front and center in the effort to nominate the telegenic Kamala Harris for the White House. Harris claims multicultural California represents “the future” being created by very diverse millennials in comparison with Trump’s white and aging base.

Yet on the ground level, the progressive regime has been far less friendly, at least economically, to minorities than most may suspect. Many live in deplorable conditions, with a rate of overcrowding roughly twice the national average. Minority home ownership is plunging well below other states, and economic prospects, particularly for those without college education, are increasingly dismal.

Will America buy this model?

Brown’s successor, notionally former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, will someday have to confront the reality in places — South Los Angeles, Santa Ana, San Bernardino and Fresno — where the wealth of Facebook, Google, Apple and Disney barely reaches. The state is home to a remarkable 77 of the country’s 297 most “economically challenged” cities based on levels of poverty and employment, suffering the highest poverty rate of any state, well above the rate for such historically poor states as Mississippi.

Today, according to the Social Science Research Council, California now has the greatest income inequality in the nation, suggestive of a disappearing middle class. In the past many people dreamt of moving here. Now it attracts less newcomers per capita than virtually any state; only four states — Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin and Illinois — fared worse in bringing in new taxpayers.

Today, domestic net out-migration, even after declining in the early years of the recession, has more than doubled between 2013 and 2016. Even worse, according to a recent UC Berkeley study, over a quarter of Californians are considering a move, half of them out of the state, with the strongest proclivity found among people under the age of 50. And contrary to some progressive commentary, those leaving are not necessarily old or losers; according to IRS data, out-migrant households had a higher average income than those households that stayed, or of households that moved in to the state.

Paragon, cure thyself

Rather than serving primarily as a role model, California today should be seen as much a cautionary tale. We certainly produce great wealth, but also far too much poverty. To be sure, California is now home to four of the 15 richest people on the planet and 70 percent of the 56 billionaires under 40; the Bay Area remains the most prodigious producer of high wage tech-related jobs.

But for much of the middle and working classes, more serious has been the erosion of higher-wage blue collar jobs, which have dropped by 500,000 since 2000 and by over 300,000 since the Great Recession alone. In contrast, minimum or near-minimum wage jobs accounted in 2015-16, notes the state’s Business Roundtable, for almost two-thirds of the state’s new job growth.

None of this suggests that California is doomed, or has descended into the hell suggested by some conservatives. But before recommending our policies to the nation, we need to address the issues that threaten to tear our society apart.

Of course, even in the light of the Facebook scandals, much of the country will continue to admire our innovators and embrace our stylishness and multi-cultural creativity. But much of the rest of the country is unlikely to buy the California model until it starts to address fundamental issues such as class mobility, affordability and education. Until then, we may be first in the hearts of progressive activists, but not so much for everyone else.

(Joel Kotkin is the R.C. Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University in Orange and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism, www.opportunityurbanism.org. He is an occasional contributor to CityWatch.)

-cw