CommentsCONNECTING CALIFORNIA-Who is the most powerful governor in California history? The next one. Over the past four decades, our state’s governorship has grown so great in reach and power that it now constitutes a second American presidency.

California governors sign international treaties and agreements, and are treated like national leaders at the biggest global gatherings. They head a state government so powerful and sophisticated that it sometimes operates as a fourth branch of American government—employing regulations, lawsuits, and the size of the California market to check the president, Congress, and even the courts.

Here at home, our governors dominate not only politics and policy but also California’s civic conversation itself. Since trends in the electorate, the legislature, and the media all enhance the governor’s power, the next governor is likely to be even more powerful than Jerry Brown. Which is why there should be far more attention paid to the 2018 governor’s race—and to the question of whether the governorship itself has become too powerful.

California’s centralized power contrasts with the state’s image as open and diverse, with a progressive culture and innovative technology bent on disrupting existing structures. And California has long been considered almost ungovernable—with its many different competing regions, interest groups, and local governments.

But this diversity and complexity—and the resulting frustration about getting anything done—is at the heart of the governor’s power. Precisely because it’s so hard to get attention and to orchestrate policy among so many unruly constituencies, Californians are often desperate to find someone—or anyone—with the power and agency to make a decision and accomplish what they want. And that person has been, more and more often, the governor.

For the past 40 years, voters, special interests, other governments, and even the legislature have been ceding powers to what was already a very strong executive position. California governors can issue executive orders, veto bills, veto particular line items in an appropriations bill, vote as a member of the Board of Regents, set special elections, and declare emergencies. Of course, they can grant pardons, commute sentences, and call up the National Guard, too.

Most formidably, the governor has the power to appoint more than 4,000 positions, including all judges, giving him power to control policy in areas from school curriculum to coastal protection. The governor also can fill vacancies in any statewide office, including the attorney general or controller. The only politician in this country with more appointment power is the mayor of Chicago.

In the 1970s, the governor’s authority grew as power was transferred from local governments to Sacramento in two big shifts. First, state courts, in the name of making school funding equal, took funding power away from local governments. Then voters, in the name of protecting homeowners and taxpayers, passed Proposition 13, which effectively took power over taxation away from local governments.

As Sacramento made more decisions for Californians, governors made more use of the full power of their offices to get the upper hand. Pete Wilson pioneered the use of executive orders for a host of vital policy changes. Gray Davis devised new ways to intervene in the legislative process, dismissing protests from lawmakers about his imperiousness by declaring: “Their job is to implement my vision.”

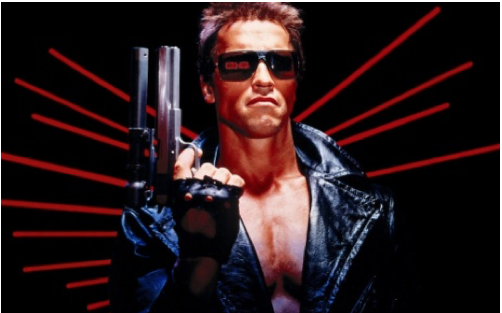

Arnold Schwarzenegger combined his celebrity, his wealth, and his office’s power to devise ballot initiative campaigns that gave him greater leverage with the legislature. Schwarzenegger also pushed through climate change legislation that empowers the state’s muscular regulatory agencies to act as both money collectors and enforcers of one of the most complicated environmental regimes on earth.

The state’s regular budget crises also enhanced gubernatorial power; governors often demanded wider room to manage the budget and the state’s cash flow, as the price of compromise with the legislature. Governor Brown also has bargained more authority; the state’s new law to establish a $15 minimum wage by 2022 gives the governor the power to delay the hike for different reasons.

Then there are the voters who, disgusted by gridlock that was easily blamed on the legislature, have often granted more authority to governors without even thinking about it. The most dramatic example was when voters installed legislative term limits in 1990. With that change, lawmakers and staffs could stay for only a few years at a time, whereas in the executive branch the governor could rely on department heads and powerful regulators who had long careers and inside knowledge.

The legislature has failed to counter such executive power—its relatively small number of lawmakers (California has the country’s smallest legislature on a per-voter basis) is stretched thin, and has little time for detailed hearings, investigation, or oversight of the governor and his administration. The legislature also doesn’t have the same institutional infrastructure to produce data and reports to guide policymaking; when legislators make laws and budgets, they often rely on the executive branch’s numbers.

As Sacramento made more decisions for Californians, governors made more use of the full power of their offices to get the upper hand.

More recent good government reforms also have weakened the legislature and thus strengthened the governor. In 2008, voters stripped the legislature of perhaps its greatest power—the power to draw legislative districts—and gave it to an independent commission. And in 2010, voters got rid of the requirement of a two-thirds vote to pass a budget, which had given the minority party in the legislature considerable power to challenge the governor.

These days, the opposition has little juice. All the governor needs is the support of the two leaders of the majority party in the legislature. In this era of one-party Democratic control, that majority party is the governor’s own party, further enhancing his power.

California’s diminished media also reinforces the notion that the governor is the only game in town. With fewer reporters covering Sacramento, the governor has become the only politician who is covered regularly. Even State Senator Kevin de León, who has been the most influential legislator of this decade and is now running for U.S. Senate, remains little known across the state.

In much of Sacramento, the power of the governor is considered a natural and even good thing. In a state so big, goes the argument, it’s good to have one elected official—the governor—who can focus attention and accountability.

Of course, that’s only true if Californians pick a governor who can use that power responsibly. And right now, few of us are paying much attention to the gubernatorial contest. Instead, Californians are deeply worried about all the power in the American presidency, and how it might be misused by the current occupant of the White House.

But the perils of runaway executive power aren’t limited to Washington D.C. Pay attention, California, because it could happen here.

(Joe Mathews writes the Connecting California column for Zócalo Public Square.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

25

Sun, Jan