CommentsTRUTHDIG--“If there is a silver lining to what is happening today, it’s that people really feel and see the urgency,” said Martha Arévalo, describing the grass-roots workers at the Central American Resource Center in Los Angeles who are trying to stop President Donald Trump’s assault on immigrants. “People who haven’t been involved say, ‘Wait a minute, we are fighting for our lives.’ “ (Photo above: United Farm Workers leader Cesar Chavez in 1975.)

I interviewed Arévalo, executive director of the center, known as CARECEN, because I wanted to know what she and other activists had learned from an earlier generation of organizers, which included farmworkers’ leader Cesar Chavez.

On this day, the Trump administration intensified its efforts to deport a large number of immigrants shielded by Temporary Protected Status (TPS). TPS was granted to immigrants from El Salvador, Honduras, Haiti and Nicaragua who could not return to their countries because of damage from natural disasters, civil war and other calamities. Trump’s chief of staff, John F. Kelly, pressured his successor as chief of the Homeland Security Department to speed up the deportation of Hondurans, The Washington Post reported. They are part of the some 11 million unauthorized immigrants facing deportation.

Arévalo and CARECEN are part of the latest chapter in the long, compelling history of organizing Latinos against the forces which have oppressed them since California was taken from Mexico by the United States in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48.

Anyone who thinks democracy is dying or dead under Trump should visit CARECEN, or other immigrant advocacy organizations. There, women and men, including high school students, are resisting the administration’s assaults in ways that would make their forebears proud.

I parked in front of CARECEN headquarters in Los Angeles’ Westlake district, a crowded neighborhood that is home to poor Central Americans, mostly from El Salvador, living in old apartment buildings on streets filled with peddlers, shoppers, gang members and parents walking their kids to school. A CARECEN worker met me in the lobby and took me to Arévalo’s office. Wearing a blue CARECEN shirt and seated at her desk, she was a friendly woman who seemed pleased I was there. Busy-looking staff members and volunteers passed by in the hall.

I told her I thought this was an opportune time to interview her, just as the TPS struggle is beginning.

“It is in a very interesting moment, for sure,” she replied.

Interesting is a mild word for what members of CARECEN and other Latino community organizations face as they put together demonstrations, voter registration and citizenship campaigns to fight Trump.

These community workers have learned from an earlier generation of grass-roots organizers, who worked in Boyle Heights and other East Los Angeles neighborhoods, several miles east of the CARECEN office in an area equally poor and crowded.

These lessons go back to old LA, when Latinos were a disenfranchised and oppressed minority. In 1943, sailors raged through downtown Los Angeles beating up Latino young men in the infamous Zoot Suit riots. Police let it happen. In 1951, Los Angeles police savagely beat several Latino youths held in jail on phony drinking charges in what became known as “Bloody Christmas.”

Schools were segregated and deplorable. Latinos and African-Americans were barred from public swimming pools except for Thursday, pool-cleaning day. Housing was segregated. Political participation was weak. Into this prejudice stepped a young community organizer, Fred Ross, an associate of a legendary battler against oppression, Saul Alinsky (founder of the Industrial Areas Foundation). Ross had been a relief worker during the Depression and had brought democratic practices and decent conditions to the farm labor camp featured in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.”

In 1947, Ross, along with other Latino community leaders and progressive Jews, who were then a substantial part of the varied East Los Angeles population, founded the Community Service Organization (CSO). Alinsky, based in tough Chicago, didn’t like the name. It made “the Junior League sound militant, ” he said.

“The group’s innocent name masked its radical mission,” Gabriel Thompson wrote in The Nation. He is the author of “America’s Social Arsonist: Fred Ross and Grassroots Organizing in the Twentieth Century.” Thompson, in his Nation article, said, “In five years, the CSO had registered thousands of Mexican-American voters, had elected a Spanish-speaker (Ed Roybal) to City Council (and later to Congress), and pushed the first excessive-force convictions in the history of the Los Angeles Police Department.”

Because of Ross, Chavez, farmworkers leader Dolores Huerta and other organizers, attitudes in the Latino community changed.

Fred Ross’ son, Fred Ross Jr., himself a union organizer, told me, “They are no longer looked at as victims of injustice, but as potential warriors for justice. You put them in battle, that experience of being in a fight changes you, especially if you win every once in a while.”

More Latinos were elected to local and state offices and to Congress. Latinos, helped by CSO, joined with African-Americans and Jews to elect an African-American, Tom Bradley, as mayor of Los Angeles. A Latino, Antonio Villaraigosa, was later elected mayor, served two terms and now is running for governor of California.

Ross brought Cesar Chavez into the CSO, and Chavez recruited another dynamic organizer, Miguel Contreras, who later headed the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor until his death in 2005.

“Miguel Contreras, he was the game changer,” said Victor Narro, project director for the UCLA Downtown Labor Center and a UCLA law professor. Narro has led organizing drives among poor Latino immigrant day laborers, domestic workers, garment workers, car washers, gardeners and hotel employees.

Contreras changed the game, Narro said, by expanding organizing efforts to Central American immigrants. That was the key to a winning strike in the 1990s against owners of Los Angeles high-rise buildings, who underpaid their janitors and denied them benefits. The campaign was called “Justice For Janitors.” Los Angeles police attacked and battered the red-shirted janitors who were demonstrating at Century City office buildings, but the strikers persisted. Justice for Janitors upended the labor union perspective on how to organize, Narro said. “The labor unions were very suspicious of organizing immigrants. That changed with the 1990s with the janitors and [then with] hotel workers.”

Organizing often begins by gathering volunteers in homes—with a meal. “Fred Ross believed food is the essence of organizing,” Narro said. Ross biographer Thompson told me, “There would be five or six or eight people. You get to know people, build an organization that is intimate, but big enough to touch a lot of people.” In the 1940s, Latino vets, returning from the war, gave the movement additional energy.

CARECEN and the other organizations adopted CSO methods. Volunteers are recruited from friends, family, members of sports teams and other places where the community gathered. They learn the importance of becoming citizens, of voting and getting people to the polls and of providing important services to members.

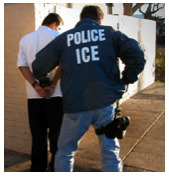

At a Day Laborer Organizing Network office, I’ve seen how volunteers are shown how to deal with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) cops rounding up immigrants: Don’t answer questions; demand to see a warrant; don’t let them in your home.

The same lessons are in a video made by CARECEN high school students. At CARECEN, I saw mothers learning child care skills. There are English, computer and citizenship classes. And they are shown how to help election turnout even if they, as undocumented immigrants, can’t vote. Everyone, after all, has friends, relatives or soccer teammates who are eligible for citizenship and to vote.

Fred Ross Jr. compared his father’s time in the CSO to what is happening today among the Central Americans, both those with immigration documents and those without. “The CSO experience and model provides a concrete path to building po litical power with a group of people who have been terribly discriminated against,” he said. “When they had an opportunity to organize, they grew as leaders.”

Fred Ross Jr. compared his father’s time in the CSO to what is happening today among the Central Americans, both those with immigration documents and those without. “The CSO experience and model provides a concrete path to building po litical power with a group of people who have been terribly discriminated against,” he said. “When they had an opportunity to organize, they grew as leaders.”

Their skills are being tested as ICE officers prowl courthouses, day labor centers, school areas and knock on home doors. ICE personnel also stop cars, demanding passports from Latinos and threatening to arrest anyone with out them. The young dreamers in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and the others live in fear of deportation.

More empowered than before, the immigrants, documented and undocumented, are saying no to Donald Trump and his immigration cops.

Their history includes the young men who resisted in the Zoot Suit riots in 1943 as well as the red-shirted Justice For Janitors strikers in the ’90s. Constituting a new chapter are today’s high school students making a video on how to resist ICE. All of them are an inspiring part of the American story.

(Bill Boyarsky is a columnist for Truthdig, CityWatch, the Jewish Journal, and LA Observed. This piece was posted first at Truthdig.com.) Photo: Jacquelyn Martin / AP.

-cw