CommentsDEEGAN ON LA-Movie mogul and studio owner Jack Warner helped to build Hollywood, a town that is now slowly being broken down like the set on one of his many movies. But it’s not movie crews who are doing post-production tear-down. It’s developers and politicos who are striking the set every time they collaborate to replace a successful expression of Hollywood architecture with their version of the sequel. Each demolition tears away at Hollywood’s history and destroys the character and fabric of Hollywood neighborhoods.

Preserving buildings and repurposing their interiors is a concept that hasn’t taken hold yet in Hollywood, unlike the way it has in downtown Los Angeles.

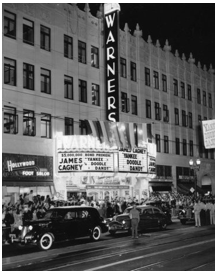

Although Jack Warner was a movie maker, he was also a movie exhibitor. His premiere local showcase was the Warner Hollywood Theater on Hollywood Boulevard, which was declared as Historic-Cultural Monument Number 572 by the City Council in 1993. Now, a quarter century after that designation, debate rages about what to do with the building, currently owned by the Pacific Theaters Corporation, which has rebranded it as the Hollywood Pacific Theater.

Before the Paramount Consent Decree in 1948, movie producers could also be exhibitors -- studios could own theaters in a vertically integrated business model. But, in “United States v. Paramount Pictures,” the Supreme Court ruled this was an antitrust violation and ordered a split -- producers and exhibitors could no longer be the same party. Before that, though, it was the theaters that had the upper hand as the guaranteed sales outlets for the movies the moguls made. No wonder the early moguls like William Fox, Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner (and his brothers) wanted to control the fate of their movies by owning theaters.

While Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer got the publicity as the studio with “more stars than there are in the heavens,” feared MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stood hat-in-hand at Union Station to greet Loews Theaters head Nicholas Schenck when he traveled from his New York headquarters to check up on how the production studio in Culver City was doing. Schenck wanted to ensure that movies would be constantly fed to Loews Theaters, the theatrical exhibition company that Mayer reported to. Loews had purchased Metro Pictures and Goldwyn Pictures and merged them with a small independent production company in Hollywood operated by Mayer. This is how MGM was born, and it was used by Marcus Loew -- the man the all-powerful Nicholas Schenck himself went to for his instructions -- to keep the product flowing into his theater chain.

While Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer got the publicity as the studio with “more stars than there are in the heavens,” feared MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stood hat-in-hand at Union Station to greet Loews Theaters head Nicholas Schenck when he traveled from his New York headquarters to check up on how the production studio in Culver City was doing. Schenck wanted to ensure that movies would be constantly fed to Loews Theaters, the theatrical exhibition company that Mayer reported to. Loews had purchased Metro Pictures and Goldwyn Pictures and merged them with a small independent production company in Hollywood operated by Mayer. This is how MGM was born, and it was used by Marcus Loew -- the man the all-powerful Nicholas Schenck himself went to for his instructions -- to keep the product flowing into his theater chain.

That’s how important movie theaters were. They were the tail that wagged the “major motion picture studio” dog. Movie moguls and famous producers were better known, compared to the distribution and exhibition executives, but were secondary characters when it came to green-lighting the final decision of where and when a movie would play before the public.

Choice theaters, like the Warner Hollywood, were the crown jewels of the movie business. A beaux-arts Italianate masterpiece built by noted architect G. Albert Lansburgh, the Warner Hollywood opened on April 26, 1928.

Conserving that link to Hollywood’s history is why the debate concerning the future of the Warner Hollywood theater is so important. Slowly, our handshake with the past is losing its grip. Soon, if we are not careful, the visual evidence of that past will turn into memories and become ghosts, lost forever. And so much damage has already been done to the fabric of Hollywood’s important buildings and what they represent.

The Warner Hollywood theater was built in an era when movie theaters were destinations for cultural and social engagement offering surroundings fit for a king, sometimes called “dream palaces.” Today, when you can “screen” a movie on your Apple Watch, the visceral connection with our movie past will be lost if we are no longer able to sometimes watch a movie from one of the 2,756 seats at the Warner Hollywood, or others like it, sharing the experience with hundreds or thousands of fellow movie-goers.

The relevance of movie theaters as cultural institutions has fallen off dramatically. What’s left of the shrinking supply of these original movie theaters is our link to the heritage of Hollywood. They were places where dreams exploded on the giant silver screen, like Jack Warner’s own dream of using his newly acquired Vitagraph sound technology to premiere the first talking movie, The Jazz Singer. He shifted that opening to New York, though, breaking the sound barrier at Warner’s Theater on Broadway before bringing it to the Warner Hollywood, where it caused a sensation and made history. Theaters became as important to Hollywood history as the movies that were shown in them.

Old Hollywood buildings tell stories that connect us to our past and this cannot be undervalued. But repurposing these great buildings instead of tearing them down rarely happens. It’s likely, however, that the Warner Hollywood will dodge the wrecking ball and the Pacific Theaters Corporation will find another use for its interior while maintaining the monument-protected exterior -- unlike the untold numbers of other buildings that have been demolished. The forecast is bad, though, for the future of many historic buildings, judging from the number of cranes visible across Hollywood.

Pacific Theaters Corporation, with its own legacy of owning first-rate movie theaters in the region and the multi-generational Forman family in the leadership position, has an opportunity to preserve the Warner Hollywood theater. It can support the community’s desire that it be turned into a legitimate space -- not another bar or club – a space that serves a public purpose. Pacific President Christopher Forman may need to have some more dialogue with the community about this.

Forman may even want to consider linking to the past by reinstating the Warner name on the project. Nothing says “Hollywood” the way that Warner Hollywood does.

Here are some interested parties that should know that #Hollywood Monuments Matter.

Get into action by contacting:

Christopher Forman - President

Pacific Theaters Corporation (owner of the Warner Hollywood building)

(310) 659-9432

Mitch O’Farrell, Councilmember CD 13 (Hollywood)

213-207-3015

Chris Robertson - Planning Deputy for CD13 (Hollywood)

213-473-7013

L.A. Conservancy

Adrian Scott Fine, Director of Advocacy

afine@laconservancy

(213) 430-4203

Hollywood Heritage

www.hollywoodheritage.org/

323-874-4005

L.A. Historic Theatre Foundation

Escott Norton - Executive Director

http://www.lahtf.org/

213-999-5069

(Tim Deegan is a long-time resident and community leader in the Miracle Mile, who has served as board chair at the Mid City West Community Council and on the board of the Miracle Mile Civic Coalition. Tim can be reached at [email protected].) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

-cw