CommentsPOLITICS--When newly-elected Donald Trump took his family to a restaurant for dinner without telling the public recently, the press flipped out. A chorus of complaints swelled across the land and apoplexy ensued among the news media.

“He didn’t tell us!”

“He’d supposed to let us know!”

“That’s not how it’s done!”

“We should have come along and sat outside while he ate steak!”Journalists and editorial writers pilloried Mr. Trump for leaving home and traveling five blocks to a restaurant. Those same reporters, along with editors and news executives, issued thoughtful pleas about the importance of documenting a chief executive-to-be’s movements.

I’m not here to defend the president-elect’s behavior or suggest that his unwillingness to play by traditional rules of engagement with the press is not a big deal. I’m a newspaper reporter, after all. And as the City Hall reporter for the only newspaper in McComb, Mississippi, I hardly find it remarkable when the mayor travels the three blocks from his office to the Dinner Bell restaurant without first notifying me.

I am here instead to suggest—from deep and unusual personal experience—that the news media and everyone else might do well to prepare for a lot more breaking of protocol.

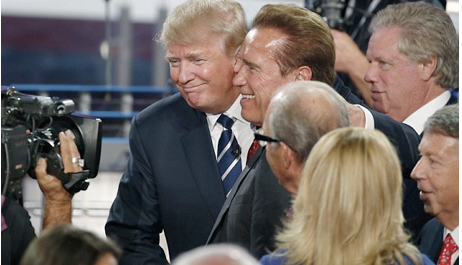

I was the personal aide, AKA “Body Man,” to a governor of California who at the time of his election was one of the five or six most famous people on earth. Like Donald Trump, Arnold Schwarzenegger proclaimed himself an outsider, a non-politician. His first campaign, like Trump’s, was a circus, with the sheer force of his persona flattening most criticisms and every opponent.

“I’m rich so I’m not beholden to special interests,” he said. “I’ll fix a broken system,” he said. Trump’s “drain the swamp” sounds a lot like Schwarzenegger’s “blow up the boxes.”

There is of course a vast difference of scale between a president and a governor, even a superhuman governor like Arnold Schwarzenegger. A governor isn’t responsible for national defense and doesn’t negotiate treaties with other countries. A governor doesn’t tend to travel in a 50-vehicle motorcade with an ambulance in it. A governor doesn’t have access to nuclear codes.

But I believe there are lessons to be learned from Schwarzenegger’s behavior as governor that will help us understand Trump’s as president, at least based on how he has conducted himself in the first weeks since his election.

Early in the Schwarzenegger era—like Trump, even before he took office—calls of “It’s always been done this way” began to be tossed about.

“You’ll have to be in the Capitol every day to meet staff and legislators. You’ll have to be here to sign bills. That’s how it’s done.”

It took a while, but Arnold chipped away at “It’s always been done this way” until the Sacramento apparatchiks got it through their heads that the governor could do business sitting by his swimming pool 400 miles from the Capitol if he wanted to.

One thing people didn’t press the governor to do was move his family from Los Angeles to Sacramento. California was at the time one of just a handful of states with no governor’s residence. That and Arnold’s four school-age kids gave him a pass on the relocation bit.

Instead he took up part-time residence in a two-bedroom hotel suite across the street from the State Capitol. Several nights a week, he slept in one bedroom, I in the other. Between the manly-man Republican action hero and the 40-something gay Democrat, we were an odd couple if ever there was one.

“What must people think … the two of us living here like this?” he said one night as he switched off the lamp in our living room before heading to his bedroom. But I don’t believe he fretted much about what people thought, about his living arrangements or anything else.

It took a while, but Arnold chipped away at “It’s always been done this way” until the Sacramento apparatchiks got it through their heads that the governor could do business sitting by his swimming pool 400 miles from the Capitol if he wanted to. Staff could fly to Los Angeles, their rolling suitcases, jammed with legislation, in tow. The mountain, it turned out, could indeed come to Mohammad.

In August 2004, less than a year after Arnold took office, he agreed to speak at a high-ticket Bush-Cheney fundraiser in Santa Monica. Our advance people and the California Highway Patrol team warned, “Governor, the Secret Service say you have to be there 30 minutes ahead of the president or they won’t let you in. They’ll shut down access.”

“Relax,” Arnold said, just as I heard him say several times a day for the seven years he held office. “Let’s go to Starbucks.” There were few things Arnold Schwarzenegger liked less than sitting and waiting. “No hanging” was a mantra.

“But Governor, the Secret Service …”

“Starbucks. Do you really think they’ll keep me out?” And he was right. He knew the power of his celebrity. Starbucks was a frequent tool for the killing of time, and the California Highway Patrol protective detail learned quickly to research Starbucks locations when plotting routes between events.

There is shorthand for a politician’s unplanned events or stops on a tour. An OTR, or Off The Record, is an unscheduled stop. There was the OTR at an H&M store in Philadelphia, where Arnold had seen interesting scarves in the window when driving past.

“What are you doing here?” the lady behind him in the checkout line asked.

“Buying scarves.”

“Makes sense,” she said.

OTRs are easier when you have your own airplane that won’t take off without you, as the governor did.

“Do you really think they’ll keep me out?” And he was right. He knew the power of his celebrity.

Then there was the jet ski OTR in Miami Beach. We were there for a conference on climate change but, as at most conferences, Arnold didn’t attend every panel, plenary, and roundtable.

“Let’s get some jet skis.”

“Uh, you’re supposed to be in the reception at 3.”

“Relax.”

Several staff members had to make quick trips to the hotel gift shop for swim trunks; others of us knew enough to have packed apparel for every Florida eventuality. It had to be an odd picture, Schwarzenegger and his posse traipsing across the sand to the surf, flanked by a team of plainclothes highway patrolmen in dark suits. It happened that we were crossing a topless beach but if the rest of the posse was titillated, I was not.

More times than I can count, the governor visited construction sites or industrial facilities where hardhats were required.

“Not gonna happen,” he would say, not breaking stride, to the man waving a hardhat in front of him.

“But it’s required!” By then it was too late.

He acquiesced only once in the headwear department, though it wasn’t with a hardhat. At Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem, a yarmulke is required when you enter the Hall of Remembrance to view the Eternal Flame. That time, the governor knew better than to quarrel.

Arnold’s reluctance to commit to schedules or events until the last minute sometimes meant squads of CHP officers sitting and waiting to cover every possible scenario. Teams gamely stationed themselves everywhere he was scheduled to go, or where he might go when he made up his mind. And if he decided not to go, the team drove or flew home, depending on how far away they were.

I made a wasted trip once myself. I had been dispatched to Idaho to set up a retreat for the governor’s senior staff in his vacation home. But as soon as I landed in Boise I received an email telling me to come back to California. The retreat was off. I hustled across the airport and made it onto a plane leaving just a few minutes later, but that was a $700 ticket on the state’s dime.

Despite Donald Trump’s thumb-your-nose approach to the traditional ways of doing things, I don’t think we’ll see him in H&M buying five-dollar scarves. But he could if he wanted to. And like the H&M visit, I don’t expect to see President Trump sea-doo-ing anytime soon. But one never knows.

One thing we can expect from President Trump is that “it’s always been done that way” won’t get us very far. We won’t like everything he does but we shouldn’t be surprised when he defies protocol. After all, breaking the rules of presidential campaigns is what got him elected.

(Clay Russell is a reporter for the McComb (Miss.) Enterprise-Journal and prides himself on his non-linear life path. A former professional chef, he lives with his husband and two cats in America’s Deep South. This piece was posted first at Zocalo Public Square.)

-cw

Explore

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

28

Mon, Apr