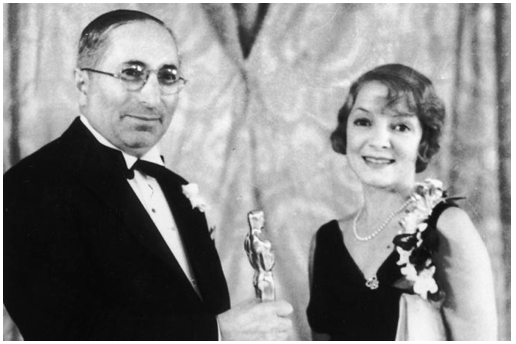

CommentsOSCAR POLITICS--If Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s legendary co-founder Louis B. Mayer (Photo above, with actress Helen Hayes) were alive today, he would likely applaud the boycott of the Oscars, but not necessarily in protest of the lack of racial diversity at Hollywood’s preeminent awards ceremony. It would be to rail against the presence of all the card-carrying members of the Teamsters, the Screen Actors Guild and numerous other unions of the film industry’s highly organized workforce.

As a fascinating 2014 Vanity Fair article reported, the Academy Awards were birthed in 1927 by Mayer and his fellow studio bosses in large part to head off labor disputes and discourage actors, directors and writers from demanding health benefits, pensions and residuals. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences would do the dirty work of keeping costs down, while throwing an annual bash to celebrate Hollywood’s biggest and brightest stars.

The Oscars eventually became a global sensation, but the union-bashing part of the plan didn’t go as well. By the 1930s, screenwriters, directors and actors had organized, parlaying their considerable clout into real economic power. Over the next several decades, tens of thousands of below-the-line industry workers -- everyone from grips and electricians to make-up artists and stylists to projectionists and sound technicians -- followed suit.

By the 1940s, Hollywood was a union town. Today, there are nearly half a million unionized workers in the U.S. entertainment industry -- a stark contrast to the decline of organized labor in most sectors of the economy.

With the gap between the haves and have-nots widening and the economic disparity separating the country’s top income earners and the rest of America a main tenet of this year’s presidential election, it’s important to recognize the overwhelming success of the organized entertainment industry. It is a prime example of an industry doing right by its workers - mostly middle-class earners just looking to make a living - while also enjoying huge financial success.

A large percentage of these workers are in Los Angeles, forming one of the cornerstones of the city’s middle class. As the Southern California economy was buffeted by the loss of good jobs in aerospace, manufacturing and other sectors in the 1990s, the film industry was a pillar of stability. While the phenomenon of runaway production has taken a toll, nearly 200,000 California workers are still employed in the film and TV industries, and those numbers may grow now that the state is taking aggressive action to keep productions here.

How important are good union jobs to LA’s economy? Consider this: Between 2011 and 2013, L.A. County had the highest poverty rate in California, with a quarter of all residents falling into the ranks of the poor. In the City of Los Angeles, a much larger number, in excess of 45 percent, struggle to make ends meet with wages of less than $15 an hour while technically not qualifying as poor. L.A.’s minimum wage hike will help, but by the time workers benefiting from the law passed earlier this year are earning a $15 wage in 2020, the middle class will still be out of reach.

By contrast, the majority of below-the-line workers in Hollywood, while far from affluent, make enough money to support their families. Camera operators average $58,000 a year, animators and multimedia artists earn $60,000, electricians and lighting workers make $71,000. Less-skilled workers earn lower pay, but still make considerably more than they would doing comparable jobs in non-union industries.

Hollywood salaries would look a lot different if MGM’s Mayer and his fellow studio heads had prevailed back in the 1920s. Los Angeles, and the country, are far better off because they didn’t.

(Cherri Senders is founder and publisher of Labor 411, a consumer guide to companies that treat their workers fairly. She can be contacted at [email protected].)

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

22

Mon, Dec