CommentsE RECALLUS UNUM - The recall—the tool being used in an attempt to remove Gavin Newsom as California’s governor before his term is over—might seem strange or novel. It’s neither. The recall is nearly as old as democracy itself.

It’s older than Montesquieu, the famous 18th-century French nobleman and philosopher, who argued that elected representatives “should be accountable to those that have commissioned them.” The recall also pre-dates Montesquieu’s contemporary, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who in The Social Contract wrote, “the holders of executive office are not the people’s masters but its officers [and] the people can appoint them and dismiss them as it pleases.”

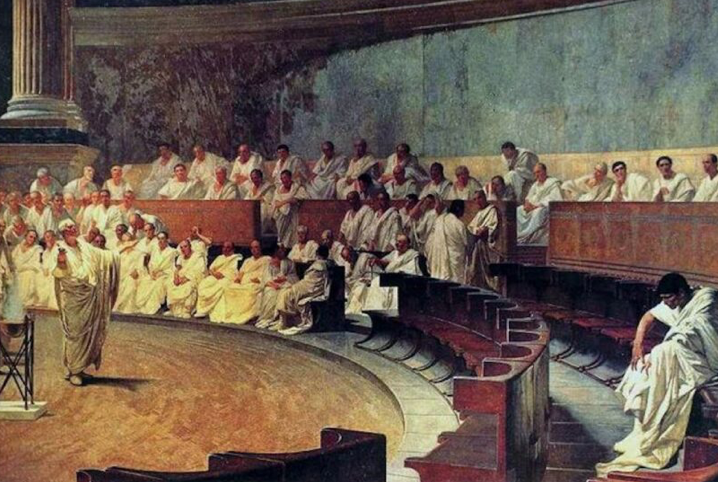

Indeed, the recall first appeared in the Roman Republic where, in 133 BC, the tribune Octavius—according to Plutarch’s account—was recalled after he had vetoed a senate Bill. In the Middle Ages, the prominent philosopher Marsilius of Padua (1275–1342) acknowledged the citizens’ right to “remove rulers from office who betrayed their trust.” And, a few hundred years later, the radical Levellers of 17th-century England espoused the device; some even believed members of the House of Commons should be subject to revocation, mentioning the power of “removing and calling to account magistrates” in the 1647 Agreement of the People. (This recall never went into effect, however.)

When America seceded from Britain, in 1776, the idea of the recall—perhaps inspired by Montesquieu—found its way into the U.S. Constitution’s precursor, the Articles of Confederation. These provided for the “recall and replacement of delegates even within their one- year term.” The mechanism was even included in James Madison’s first draft of the U.S. Constitution. The so-called Virginia Plan stated unequivocally that “members of the National Legislature” should be “subject to recall.” When this draft was rejected, the lack of a recall provision in the U.S. Constitution was one of the main objections raised by the anti-Federalists. “Brutus”, the pseudonym used by one leading opponent of the document, wrote: “It seems an evident dictate of reason, that when a person authorises another to do a piece of business for him, he should retain the power to replace him.”

Likewise, in the heated debates in the New York ratifying convention, New York delegate Melancton Smith—believed to be Brutus’ alter ego—again defended the recall, noting that it would be used sparingly. “The power of the recall would not be exercised as often as it ought. It is highly improbable that a man, in whom the state has confided, and who has an established influence, will be recalled, unless his conduct has been notoriously wicked,” said Smith. Despite these arguments, his proposal for a recall was rejected as too radical.

Discussions about the recall were not revived until after the American Civil War. In the 1880s, as a result of what was perceived as the corruption of the political system, so-called Populists championed the use of referendums, initiatives, direct elections of senators, primary elections, and the recall. The movement in favor of these reforms had a distinct left-wing tenor, with Social Labor parties joining the Populists.

In Europe, the recall was associated not just with left-wingers, but with revolutionaries: Rosa Luxemburg and Antonio Gramsci were both advocates. Karl Marx made a case for recalling elected representatives in his pamphlet The Civil War in France. Marx wrote approvingly about the system under which all the elected representatives’ mandates were “at all times revocable” Inspired by Marx, Vladimir Lenin made a case for a “fuller democracy” in which all officials should be “fully elective and subject to recall.” This was the only way of overcoming the problem of parliamentarianism, namely “deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to represent people in parliament.”

Marx wrote approvingly about the system under which all the elected representatives’ mandates were “at all times revocable” Inspired by Marx, Vladimir Lenin made a case for a “fuller democracy” in which all officials should be “fully elective and subject to recall.”

That the recall was a central plank, perhaps even the lynchpin, of Lenin’s theory of representation is also evidenced by a short essay he wrote weeks after the Revolution. “Democratic representation exists and is accepted under all parliamentary systems, but this right of representation is curtailed by the fact that the people have the right to cast their votes once in every two years, and while it often turns out that their votes have installed those who oppress them, they are deprived of the democratic right to put a stop to that by removing these men,” he wrote.

Lenin cited “cantons in Switzerland and some states of America” as places where “this democratic right of recall has survived.” But, perhaps more interestingly, he also suggested that the recall could have made the revolution less violent and that the right of recall held out the prospect of a peaceful means of resolving political problems. Rather than “a rather stormy revolution”—his description of the storming of the Winter Palace—there could have been a peaceful change of power. “If we had had the right of recall,” he reflected, “a simple vote would have sufficed” to remove the provisional government.

In practical politics, the recall remained part of the formal institutions in the Soviet Union, but it was not used before the last decade of communist rule, when the citizens were allowed to use the provisions during the Glasnost period under Mikhail Gorbachev, when two deputies were recalled in Sverdlovsk.

The attempts to introduce the recall into practical politics in Europe mostly failed. True, several German cities and nine states adopted the recall during the years of the Weimar Republic (often at the instigation of moderate socialist politicians). But the provision was of little practical importance.

The recall would gain far more acceptance in the United States, where Americans saw the recall less through the words of European revolutionaries, and more through the special Swiss experience with the recall and other forms of direct democracy.

The American Labor leader J.W. Sullivan’s influential 1892 book, Direct Legislation by the Citizenship, was explicitly based on the author’s impressions from a trip to Switzerland, and he wrote enthusiastically about how “the people may recall their servants at brief intervals.”

Sullivan—like other Americans advocating the use of the recall—argued not for Marxist revolution but for establishing more efficient checks and balances. As William B. Munro, another American populist, suggested, “the chief argument in favour of the recall as advanced by friends of this expedient, is its efficacy as an agent of unremitting popular control over men in public office.”

In a creative analogy later cited in court cases supportive of the recall, Munro found that the tool was an application of the principle of ministerial responsibility, which is a feature of the English government, and which enables the course of public policy to be altered at any moment by the recall of the Cabinet at the hands of the House of Commons.

But America’s established politicians were severely critical of the recall. President William Taft, one of its strongest critics, made a point of vetoing the proposed constitution for Arizona in 1911 (the year before the territory became the 48th state) because of the document’s recall provision. Arizona responded by removing the recall from the draft—and immediately reinstating it once statehood had been granted.

It is a measure of the importance attached to—and the dangers associated with—the recall that Taft continued his crusade against the device after he left the White House. In a series of lectures at Yale University, the former president criticized the recall, which —in his view—would create a “nervous condition of resolution as to whether he [the representative] should do what he thinks he ought to do in the interest of the public.”

Of course, this potential for keeping politicians in check, for preventing legislative activism, was the chief reason behind the Populists’ espousal of the device. “The recall,” noted Pulitzer Prize winner William A. White, the editor of Emporia Gazette and a defender of populist causes, “should make … statesmen nervous.”

In America, the supporters of the recall won the day, and it was implemented in many states at the instigation of politicians and advocates on the left.

Proponents as well as opponents of the recall had expected that the device would be used predominately against judges. This turned out not to be the case. Between 1910 and 1940 only two judges—both of whom had given lenient sentences to rapists—were recalled. It is noteworthy that the California Bar Association was sufficiently concerned about the damage the judges were doing to the legal profession to support the recall.

But overall, the recall is used sparingly at the state level; North Dakota’s governor Lynn Frazier was recalled in 1921, and California’s Gray Davis in 2003.

Newsom, if removed from office, would be just the third recalled governor, in more than a century of the recall’s use in America.

MATT QVORTRUP is a professor of political science at Coventry University in England and the author of more than a dozen books on democracy, the most recent of which is Democracy on Demand: Holding Power to Account, from which this essay is adapted.