CommentsCONNECTING CALIFORNIA-The attempted recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom has many geographic roots. Its original proponent was a sheriff’s deputy from Yolo County.

The recall petition drew signatures from significant percentages of the population in our smaller, North State counties. And East Coast conservative media and right-wing Republicans from other parts of the country have given it attention and money.

But a recall is about replacing one governor with another. And, for the second gubernatorial recall in a row, it is the frustrations of San Diego County, and its ambitious politicians, that are driving the process.

Back in 2003, the frustrated and ambitious San Diegan behind the recall of Gov. Gray Davis was Congressman Darrell Issa. An ordinary gubernatorial election didn’t hold much hope for a conservative Republican like Issa, but the recall election -- with a huge field of replacement candidates -- seemed to provide an opening. So, Issa, a car alarm magnate, provided the money to qualify the recall for the ballot, and formed a campaign team, only to abandon his candidacy.

This time, two ambitious men from San Diego lead in early polls of who would replace Newsom if the recall succeeds.

Former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer has long eyed the governorship but seemed to be too moderate to beat a more conservative Republican in a primary election. Faulconer embraced the opportunity of a wide-open recall race and began campaigning before all the signatures were submitted this spring. Faulconer’s candidacy has given the recall, which had been backed by little-known pro-Trump activists, a bit of legitimacy; he is clearly the candidate that Newsom’s team fears most.

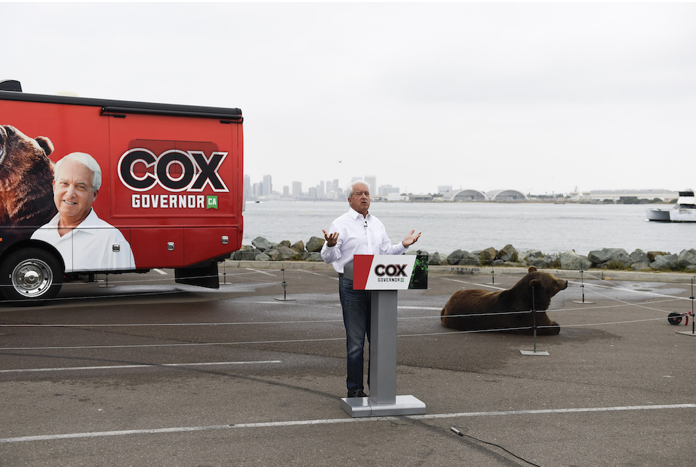

The other San Diegan, businessman John Cox, lost badly to Newsom in the regular 2018 gubernatorial election. But Cox, who has spent years searching for a way into political office, saw the recall as a second chance. He has now thrown his fortune behind the recall and his candidacy, broadcasting ads statewide that show him with a bear, to symbolize the “beastly” changes he will bring to the state.

Why is San Diego the home of recall leaders? Part of the answer lies in the state’s political change. While San Diego -- which voted Republican in 19 of 25 20th-century presidential races -- has become more Democratic, it’s still not as blue as the state as a whole. The city and county still elect Republicans like Faulconer, who is popular enough with San Diego Democrats to convince himself he might win statewide.

Another political answer to the question lies in San Diego’s little-known status as a hotbed of direct democracy. For much of California’s history, San Diego has been the easiest place to gather signatures on petitions for recalls and ballot initiatives. In some initiative campaigns, San Diego produced signatures at twice the per-voter rate of other counties.

But I suspect that San Diego’s affinity for the recall goes beyond politics. San Diego is a big place, the country’s eighth most populous city, but its cachet and influence don’t match its ambitions -- because America’s Finest City, as it bills itself, has the bad luck to be located in California.

San Diego would be the largest metropolis in 43 states, but in California, it’s an after-thought, only the fourth most populous metro region, smaller than even the Inland Empire. Its news, its sports teams, and its leaders don’t get the same level of statewide attention that San Francisco’s and Los Angeles’s do.

San Diego is also a different sort of place than its big brothers up the coast. LA and the Bay Area are global mega-regions, proudly out of step with the rest of the United States. San Diego, by contrast, is the most unabashedly American of California cities. It’s a place full of military installations and veterans, who fly their flags and host our state’s largest Fourth of July show. Its location on an international border also reinforces its American identity.

San Diegans, many of whom have dedicated their careers to defending the nation, often see the rest of California as going too far beyond American law and tradition. So, it’s not hard to see why the recall, a reactionary tool, might appeal as a way of pulling California back to reality.

But that doesn’t mean the recall will succeed in installing a San Diegan, much less slowing down change. Back in 2003, the San Diego-funded recall was ultimately won by a foreign-born movie star from Los Angeles.

It doesn’t help the prospects of Cox or Falconer that the last California governor from San Diego, Pete Wilson, who ran as a moderate, has curdled into a full-throated supporter of Donald Trump. Late in life, Wilson, whose statue was briefly taken down in San Diego last fall, defends his anti-immigration politics with the fervor of a man who wants to go down in history as California’s answer to George Wallace.

This year, San Diego’s attempts to take out Gavin Newsom have succeeded in producing another recall election, which is no small feat. But since the election became a certainty, Gov. Newsom has grown more energized and popular.

In today’s California, San Diego has enough horsepower to demand the state reconsider who should be governor—but not enough to take the reins itself.

(Joe Mathews writes the Connecting California column for Zócalo Public Square.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.