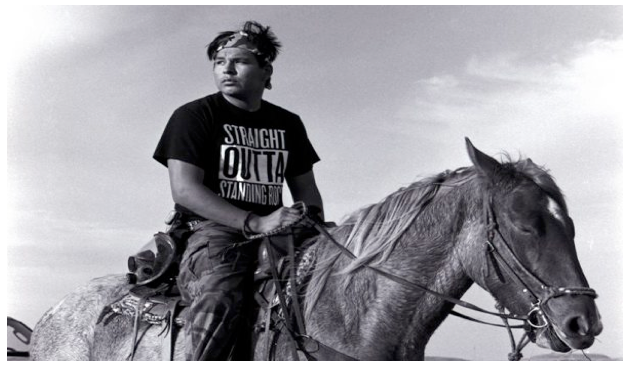

CommentsSTANDING ROCK STAND-OFF-(Editor’s Note: This is a update on Jennifer Caldwell’s earlier CityWatch article, “Thanksgiving 2016: The Worst in Seven Generation”.)In a remote, windswept corner of North Dakota, a seven-month standoff continues without an end in sight. Thirty miles south of Bismarck, where eroded buttes rise from grassland and corn fields, the Oceti Sakowin camp appears along the winding girth of the Missouri River. Here, a story of protection, protest and cultural conflict unfolds against the desolate prairie.

At issue is the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL); an “energy transfer” project that would pipe approximately 470,000 barrels of oil per day from the Bakken Oil Fields through South Dakota and Iowa, to refining facilities in Illinois. The pipeline is a 1,172 mile, 30-inch artery that is touted by its progenitor, Energy Transfer Partners, as necessary to transport light sweet crude in a “more direct, cost-effective, safer and responsible manner.”

At the juncture of the Missouri River and Fort Yates, along the northeastern edge of the Lakota Sioux Standing Rock Reservation, the project slowly churns its way toward a hotly disputed patch of land. Several hundred yards north of the camp, a lone bridge has come to define the front line of this conflict. On one side, the West Dakota SWAT Team stands watch over the DAPL’s border. On the other, two young Lakota men are charged with maintaining order among the camp’s curious and defiant. In between rest the carcasses of burned-out trucks, which several tribal “water protectors” torched in response to the past few days of skirmishes that had culminated in a volley of tear gas and rubber-bullets. A concrete barrier topped with barbed wire and decorated with vulgar graffiti exemplifies the air of tension.

The stand-off has given way to violence and threats of violence, here and well beyond the borders of the Standing Rock Reservation. While law enforcement and the water protectors engage in a guarded choreography, fear strikes in the vulnerable hamlets that dot the plains. Across the prairie, the pipeline dispute has resurrected age-old enmity between the native peoples and those they perceive to have permanently occupied the territory of native birthright.

Normally, by mid-November the ground here would be frozen with knee-deep drifts of Midwest snow. Today, however, the temperature will rise into the mid-60s with almost balmy comfort.

“This is what I call the upside of global warming,” jokes Ken Many Wounds. “Or, perhaps Great Spirit is looking out for us.” A member of the Standing Rock Lakota Sioux, Ken is an organizer and the camp’s communications director. His authority is confirmed by the company he keeps with the core leaders of the action. Ken is an imposing figure. He has rugged features and strides with a cowboy’s gait as his long wiry ponytail flows from beneath a baseball cap. Ken bristles at the term “protesters” and admonishes that those opposing the DAPL are “water protectors.”

Versed in the complex history of Sioux land disputes, Ken explains the intricacies of treaties, land grabs and the exceptions within exceptions that have chipped away at the territory of the Sioux Nation for over 150 years. “Where we stand is Sioux land, according to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851,” he says, adding that the subsequent Sioux Treaty of 1868, which the Sioux allege to have never been properly ratified, illegally redefined the borders of Sioux territory. At best, the state of ownership and land rights is nothing short of confused.

Indians and non-Indians mill around nearby, executing various tasks in the maintenance of the protest camp’s daily life. The aroma of wood fires and beef stewing in cast iron kettles fills the air. The setting sun casts a shadowy skyline of tents, tepees and converted buses, all gathered to push back at the slow, oncoming creep of the pipeline. The camp ebbs and flows in population, retaining about 6,000 inhabitants, and pushing hundreds of yards to the swampy tributaries flowing into the Missouri.

In the distance, a drilling pad pushes closer to the river with the ultimate goal of tunneling beneath it. In the process, the excavation will cut through burial grounds. Distrust of the project has intensified over allegations that non-Indian archaeologists from the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Office have been exclusively charged with identifying native graves. Equally, there is concern as to what will occur should the pipeline breach below the Missouri’s pristine waters.

On these two issues, there is an odd chorus of consensus bridging what is otherwise a de facto apartheid in this small corner of the world. On and off the reservation, the welfare of the Missouri River provokes ready conversation.

“We don’t want that pipeline coming through here,” explains a woman named Terrie in Mandan, a town of roughly 20,000 inhabitants just west of Bismarck and 30 miles north of the standing Rock Reservation. Her youthful face softens as her distrust of me thaws. “If that pipeline ruptures, it will be the end of the Missouri. That’s going to affect millions of people down-river.”

But, just as quickly as Terrie is to condemn the pipeline, her teenage daughter shows me photos of vandalism in the nearby veteran’s graveyard. The agitated teen exclaims, “Look! Look at this. These pipeline protesters went and put a Tonka truck in the veteran’s graveyard with a sign that says ‘Let’s start drilling here’!”

Terrie is angry. “Leave our veterans alone,” she says. “Why would you desecrate their graves? They have nothing to do with this.”

It’s hard not to be taken in by the women’s congenial earthiness. On the other hand, the irony of their sensitivity to a distasteful prank, and the simultaneous indifference to the impact on Native American burial grounds, is inescapable. Here, the contempt for Native Americans is palpable and ubiquitous. “They get handouts and they are taken care of by the government,” Terrie adds. “They don’t have to work for any of it.”

As much as there is division between races, there is also dissent within. Earlier in the day, a group from Standing Rock led a march to Mandan’s municipal offices. Working on a theme of forgiveness, love and peace, the group prayed for a cleansing of what they claim are the hatred and offenses of both sides of the conflict that occurred in the preceding weeks. Those actions led to the arrest and detention of Lakota Sioux who continued to languish in the Morton County Correctional Center in Mandan.

The march was in stark contrast to the more extreme “direct action” principles undertaken by elements within the camp. In silence, the demonstrators encircled the jail and courthouse and pleaded for the release of their brethren. It was a display of the diverse beliefs and tactics emerging from the reservation; the hawks and the doves form a division so easily overlooked on the erroneous assumption of a monolithic Lakota Sioux culture and a unified stance in the face of adversity.

On my way back to Standing Rock, I stop at Rusty’s Saloon in St. Anthony, a village half way between Mandan and the reservation. It is a clean and orderly establishment constructed as a lodge, and decorated with “taxidermied” wildlife. The place is awash in camos and blaze orange as hunters gather for lunch. I take a seat alongside a regular who eyes me with suspicion. Lori, the barmaid, senses my apprehension and relaxes the atmosphere with some easy talk. I oblige and the conversation soon deepens.

Before long, she voices concern about threats to local farmers, the killing of livestock and a plethora of fires and vandalism alleged to have been perpetrated by Indians. According to Lori, the acts are the product of a native reawakening of land rights and a history of intrusion. “Our children had to have an armed escort to school because of the threats over this pipeline,” Lori adds. “People here are just plain scared.”

These and other conversations reveal that, while there is agreement as to issues between those on and off the reservation, opinions are very much in cadence with peer allegiances and along the cultural divide.

The dialogue of race is different here. In contrast to the low rumble of urban settings, race-based hatred in rural North Dakota is immediately explosive. The conversations with non-Indians are rife with animus toward Indians and outsiders. Likewise, the indigenous population, on and off the reservation, offers little more warmth. There is a noticeable lack of eye contact with non-Indians and the almost obligatory dirty looks cast at the “was’ichu,” (the somewhat derogatory Lakota word for “white” and non-Indian). The culture is understandably steeped in historic distrust.

Back at the camp, three young people bide their time waiting for a march to the front lines. Today, the Standing Rock Youth Council will take an offering to those manning the SWAT vehicles. The Youth Council is a contingent of the reservation’s younger generation that is guided by the mantra of “removing the invisible barriers that prevent our native youth from succeeding.” They are steadfast in support of the water protection action. Today, they will push to the front lines in peaceful offering to the men bearing arms and armor just beyond the barbed wire.

I am confronted by the stoicism of two visiting tribal members from Michigan, and of Maria, a young woman affiliated with several North Dakota tribes. “This is not a conflict zone,” Maria explains. “It’s not a war zone. We don’t want it to be seen that way.”

Maria is correct. While tear gas and rubber bullets have been unleashed in the course of the DAPL conflict, the people of Standing Rock show no interest in having their actions seen as being at war with the outside world. This erroneous characterization, spawned by the mainstream media, has drawn an array of characters to Standing Rock — Indian and non-Indian, each seeking to make the action their own. I find myself having to fight my way through throngs of posers and protesters to get to the core Native American water protectors who are truly sincere in their actions.

Likewise, within the Indian community, as in any community, I discover a great variance of identity and adherence to the mores of Indian culture. Maria points to her companion, “Me Shet Nagle,” a visiting member of the Blackfeet Nation, and chides, “He doesn’t even know what his name means! For all he knows, he could be named after a sock!”

Me Shet Nagle meets Maria’s playful contempt with a sheepish grin. I jokingly assure that they will be portrayed in the most stereotypical manner possible. They get the humor. We all get it; the revelation of the Native American as a diverse culture with all of the beauty, humor, internal conflict and struggle for identity as any other.

Tension builds as the time to march draws near. Dozens of water protectors assemble across the bridge from the barricade. Members of the SWAT team can be seen readying themselves in the distance. The bridge is disputed territory. Leaders from the Youth Council cradle a sacred pipe and carry an offering of the life-giving water that is threatened by the DAPL. In silence, dozens march on toward the front line.

Within yards of the barricade, the council motions for all marchers to be seated. People pray. Some look woefully onward, expecting plumes of tear gas. Cameras click away over the crowd. Among this throng, a young woman carries an infant wrapped in a thick wool blanket. The group is completely vulnerable. I glance over the edge of the bridge and quickly calculate a two-story drop to the freezing water of unknown depth. If things went as they have before, pandemonium could break out with any incoming projectiles.

The leaders of the Youth Council disappear behind the burned-out trucks. A number of heavily armored police and military appear from behind the barricade to take stock of the crowd. They peer from behind dark goggles beneath Kevlar helmets, adorned in heavy flak vests, with weapons slung at the ready.

The moments linger.

Finally, the Youth Council members emerge. They slowly walk to the crowd and command that everyone rise and move forward. In unified mass movement, the marchers close another 10 yards toward the barricade and the tension heightens. The council leaders sternly motion directions and, again, everyone is seated. The marchers are entirely under the Youth Council’s control.

“We offered them water,” one leader reports as he raise a mason jar. “They would not drink from it!” A murmur spreads across the crowd. “However,” the leader continues, “they prayed with us.” His words are slow and punctuated with the tension of the moment. “We prayed together and, while they would not drink the water, the men did accept our water and rubbed it about their uniforms in a showing of respect and solidarity.”

After a long pause, a Lakota woman seated before me raises a rattle in the air and shakes it with a cry of approval. One by one, hands rise and a cheer of praise breaks the quiet. The armed troops’ act of personal solidarity and sensitivity was all they asked for. In modest triumph, the marchers make their way back across the bridge in humble silence and with a renewed hope.

In the distance, the machines churn on.

Recently, North Dakota law enforcement authorities, reacting to what they labeled a riot, turned a water cannon on hundreds of protesters and Indian “water protectors” opposed to the construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline (DAPL). Tony Zinnanti’s story describes life on and around the Standing Rock Reservation in the days leading up to the assault on the protest encampment.

(Tony Zinnanti is a lawyer, freelance journalist and photographer from Los Angeles. His legal work has included defense of activists John Quigley and Ted Hayes, and representation of members of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club. This piece first appeared in Capital and Main. Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Explore

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

29

Tue, Apr