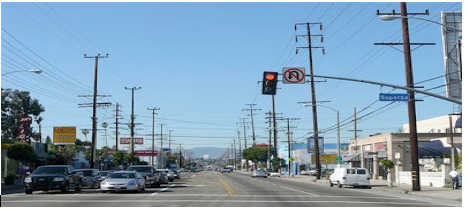

CommentsPLANNING GONE AWRY-If there are two words that joined together are a classic oxymoron, it is aesthetics and Los Angeles. Like most large cities, Los Angeles suffers from a number of forms of visual pollution, disorder and banality, including cheaply built buildings with mediocre to poor architectural quality, sign and billboard clutter, miles of overhead utility wires that further add to the clutter, a lack of consistent street trees and streetscape improvements and streets with cracks, fissures and broken down sidewalks. (Photo above: Walls of power lines line both sides of Lincoln Blvd.)

This ugliness is most evident in the unsightly commercial strip highways that crisscross Los Angeles, non-descript looking multifamily residential and commercial developments and inner city decay. As with most cities, the ugliness is not evenly distributed but is class based. It is tied to private incomes

and wealth. Los Angeles does have a few elite communities for the top 1-2 percent that are gorgeous, perfect in every way, and some additional communities for the upper middle class that are reasonably good looking but have some flaws. But beyond these top tier communities for the upper 20-25% the visual quality of the Los Angeles drops off precipitously. For the bottom 75% Los Angeles is a ugly, banal, depressing sprawl.

The smaller cities surrounding Los Angeles are nowhere near as unattractive. Most of them have buildings with higher architectural quality, business identification signs are controlled and billboards are banned, the utilities are underground or along adjoining alleys, there is a consistent canopy of street trees and street medians are often landscaped and their streets and sidewalks are in a better state of repair. This results in jarring contrasts when one crosses the boundary of one of the smaller cities and enters Los Angeles.

Examples of such contrasts are driving south on La Cienega Boulevard in Beverly Hills and then entering an ugly looking section of La Cienega in Los Angeles, traveling east on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood and then entering a miserable looking section of Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood that has been neglected for decades, driving south on Lincoln Boulevard in Santa Monica and then encountering an ugly section of the Boulevard in Venice and traveling northeast on Jefferson Boulevard in Culver City with its lush tree canopy and attractive, landscaped buildings and then encountering a barren section of Jefferson with few street trees and older, deteriorated buildings on the other side of the boundary line in Los Angeles.

And there is the contrast between the banal and ugly Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles and the attractive looking Washington Boulevard a block to the south in Culver City. In the San Fernando Valley there are the same jarring contrasts when one drives west from Burbank into Los Angeles along Magnolia, Burbank or Victory Boulevards and Vanowen Street. Indeed, one can tell when one is entering Los Angeles because that is where the ugliness begins.

For the most part, efforts to improve the aesthetics of Los Angeles have been sporadic and insufficient.

The City of Los Angeles has never had a deliberate, comprehensive program to improve its appearance. With the exception of the small fraction of the LA covered by Historic Preservation Overlay Zones and the handful of Specific Plans that have design standards and design review boards, architecture is unregulated in Los Angeles.

LA is a wide open free fire zone that allows the construction of buildings that are nondescript or downright ugly with the usual architectural “style” being the ubiquitous stucco boxes that lack the façade variations, ornamentation and sloped roofs that make a building charming and attractive. The only requirements that most new buildings in Los Angeles have to meet are the engineering standards in the Building & Safety Code to ensure that buildings are structurally sound so that they will not fall down during an earthquake.

The planning system of Los Angeles is incapable of creating the beautiful grand boulevards that one sees in the cities of Europe and in some of our older, east coast cities. Creating such boulevards would require that buildings have a consistently high level of architectural quality and similar styles.

While the City Council, after decades of voting it down, finally banned new billboards in 2002, thanks to the leadership of then Councilwoman Cindy Miscikowski, approximately 5,630 billboards remain in the City. These existing billboards cannot be removed due to a State law, A.B. 1353, that was quietly approved by the State Legislature in 1982 and which prohibits the removal of existing billboards through amortization schedules. Also, the 2002 ban on new billboards contains loopholes, such as sign district overlay zones, that still allow for the introduction of new billboards. Even though the City Council did enact an on-premise sign ordinance in 1986 that prohibits new rooftop signs and reduces the size and height of other business identification signs, a number of signs erected prior to 1986 still remain to clutter commercial streets.

While underground utilities have been required in new subdivisions since 1966, there are still many miles of existing, unsightly overhead wires in the older sections of Los Angeles put up prior to the 1960s that are untouched by that requirement. A proposal for a program to underground those wires will likely be met with resistance due to its cost and that DWP has higher priorities for its funds that involve converting its electricity sources from coal and oil to green technologies and replacing old, leaking water mains.

Similarly, a program to systematically plant street trees along the City’s major highways, to have a consistent canopy as in Beverly Hills and Culver City, will also probably face resistance due to its cost. Because the Great Recession of 2008-2009 reduced the City’s tax revenues, the City of Los Angeles had to severely cut back the number of miles of streets resurfaced each year and has spent almost nothing on repairing broken down sidewalks. A welcome development in this area is the recent settlement of a lawsuit involving unsafe sidewalks that requires the City to spend $1.3 billion over 30 years on a program to repair broken sidewalks. And with the economic recovery that has been underway since 2009 that has increased tax revenues, the City has been able to allocate more funds to resurfacing streets that have unattractive looking cracks, fissures and potholes in their roadways.

A key question regarding aesthetics in Los Angeles is why have the smaller cities been so much more successful in preserving and enhancing their appearances than Los Angeles? Because the business interests that profit from the creation of ugliness operate throughout the Los Angeles region, not just in Los Angeles, the smaller cities have faced the same pressures for “uglification.” Yet, for the most part, the economic interests have been kept under control in the smaller cities. In Los Angeles there has been insufficient countervailing power to keep special interests such as developers and the sign and billboard companies in check on aesthetic issues.

Two City bureaucracies, DWP with is many miles of overhead wires and the Bureau of Street Services that does not have a program to plant a consistent canopy of street trees, are also complicit in the creation or non-alleviation of ugliness. One explanation for the inadequate aesthetic safeguards in Los Angeles is that, because the City is so large, the residents of individual communities who would like to take control of the appearance of their communities have been out voted by the rest of Los Angeles, unlike the residents of the smaller cities have a much greater voice and influence with their City Councils.

However, this explanation is unconvincing because the Los Angeles City Council in effect operates as 15 separate cities with residents only having to obtain the support of their local councilperson with the rest of the City Council deferring to what a Councilperson wants for their district, which minimizes being outvoted. Another explanation is that the large size of Los Angeles, with each of its 15 Council districts representing approximately 253,000 residents, results in high costs for campaigns for Council seats. This in turn makes candidates for the City Council dependent on campaign contributions for developers and other business interests, resulting in politicians placing the interests of their campaign donors over those of their constituents.

This is a partial explanation. However, a more likely factor is the political/planning culture of Los Angeles. As in most places, city planning in Los Angeles is highly politicized. It is an aspect of democracy and politics with the quality of planning being done depending mainly on the quality of the citizen activists that put pressure on City Hall.

Unfortunately, for the most part, the activists have not been concerned about aesthetic issues but rather focus most of their attention on individual development projects that they deem to be out-of-scale and incompatible with the character of their communities. Their opposition has been to excessive density and height and the resulting traffic congestion.

Other activists have been concerned about threats to the natural environment. Rarely have they been concerned about architecture, sign and billboard clutter, overhead utilities or the lack of consistent street trees along the major streets. And the only persons protesting broken down sidewalks are those who have been impacted by them, who have tripped over uplifted sidewalks. Hearing few if any complaints about aesthetic issues from their constituents, City Council offices then conclude that these are not problems that deserve their attention. It will require a major expansion of the range of concerns expressed by the homeowner associations, neighborhood councils, environmentalists and individual citizens in order to generate the political will needed to address ugliness in Los Angeles.

If the political will were to be found for a comprehensive program to improve the appearance of Los Angeles, what would the program consist of? At a minimum, a program for aesthetic improvements should consist of:

- Standards for architectural quality for all commercial, industrial and multifamily residential buildings built in Los Angeles, as with Beverly Hills and San Marino. This would involve Planning Department staff checking building plans against standards of architectural quality for each identifiable architectural style, with the style to be selected by the developer. However, if a community decides that it would like to limit the range of acceptable architectural styles in order to preserve or enhance its character, it should be permitted to do so.

- Enactment by the City Council of the sign and billboard ordinance approved by the City Planning

Commission that continues the 2002 billboard ban and contains very few loopholes. New billboards that are smaller and placed against the sides of buildings to minimize clutter would be allowed only if a much greater number of existing billboards are taken down.

- A strong request from City Council to the State Legislature that it repeal A.B. 1353, which prohibits the removal of existing billboards through amortization schedules. Because a repeal of A.B. 1353 will face very strong opposition from the billboard industry lobby in Sacramento, Los Angeles will need to put together a coalition with many other cities and counties. Upon repeal of A.B. 1353, the City Council should then require that all remaining billboards in Los Angeles be removed in accordance with amortization schedules that allow sufficient time for the billboard companies to recover their investments in their signs. The City Council should expect and plan for lawsuits from the billboard companies over any ordinance that removes billboards through amortization schedules. However, billboard removal through amortization schedules is constitutional and has been periodically upheld by the courts.

- A major program by the DWP to underground overhead utilities in Los Angeles, to be financed by a temporary surcharge on DWP bills. To reduce the cost the program should be limited to undergrounding the wires along the major and secondary highways and some collector streets which, due to their high traffic volumes, are the most visible parts of Los Angeles. To further reduce the annual cost of the program should be spread out over 20-30 years.

- A major program by the Urban Forestry Division of the Bureau of Street Services to systematically plant street plant street trees along the major and secondary highways of Los Angeles, where there presently are gaps in the tree canopy or trees that are too small. To reduce the annual cost, this program should be spread out over 15-20 years.

- Increased budget allocations for street resurfacing, to resurface all streets with cracks and potholes on an accelerated schedule. In addition, implementation of the recent court settlement requiring the City to establish a program to repair broken down sidewalks.

- Economic and planning studies on the feasibility of bringing about the redevelopment of the City’s

many unsightly commercial strip highways into grand, mixed use boulevards, as called for by the Framework Element of the General Plan. Enactment of plans and ordinances containing incentives to bring about their redevelopment.

- Economic development programs to bring new and higher paying jobs to deteriorated low-income communities, to raise incomes so that it will be more feasible for developers to redevelop those communities. The development programs should look into the feasibility of re-industrializing Los Angeles, to offset the de-industrialization that has taken place during the past 40 years. Also, the City Council’s recent action to require a higher minimum wage in Los Angeles will assist in raising incomes in poor communities.

Of the items programs on this list, five (No.s 2,3,4,5 & 6) are directly under the control of government and are not closely tied the health of the economy of Los Angeles. The remaining three (Nos. 1, 7 & 8) are dependent in part on whether development activity can be redirected towards the low income communities. Standards for architectural quality, for example, will have a minimal impact if there is little or no new construction for the standards to regulate. And the commercial strip highways in low income communities cannot be improved if there is no new development along them.

The large accumulation of ugliness in Los Angeles is, in the end, a result of a lack of political will, of insufficient countervailing power against the economic interests and government agencies that have created it. It will require expanded citizen activism to overcome opposition from the interests that profit from the ugliness and the inertia of the City’s bureaucracies. The limited amount of such activism in the past is the main reason for the unattractiveness of much of Los Angeles. As Shakespeare said in his play, Julius Caesar, “The fault, dear Brutus, lies not in the stars. It lies with us”.

(John Issakson is a planning activist living in Los Angeles.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

-cw

Sidebar

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

26

Sun, Jan