CommentsSOUTH PACIFIC AVE - When I first arrived in San Pedro, the local chamber of commerce celebrated the demolition of old Beacon Street with a federally-funded urban renewal project and the town came out and celebrated with a street party.

It would be decades before the “urban renewal” dream would come to fruition and it still hasn’t fixed the economic decline. Since that time there have been three major attempts to resurrect, reconstruct and replace and/or preserve what was once a thriving hub of commerce and jobs. What is left is fundamentally connected to the goods movement industry and slowly many of those jobs are being threatened by automation.

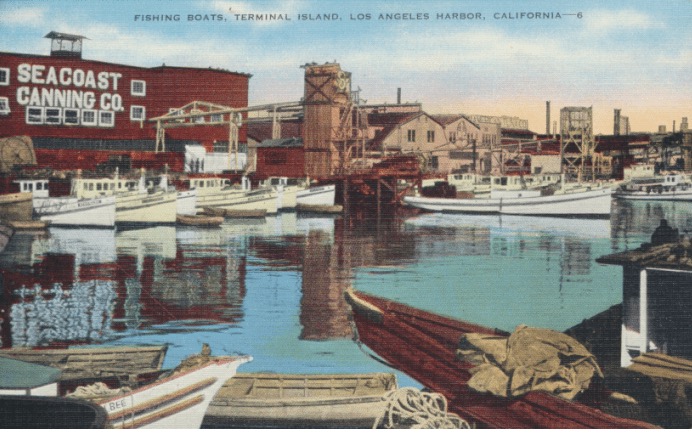

Back before the Vincent Thomas Bridge was built to connect San Pedro to Terminal Island, a small army of tuna cannery workers trudged daily up and down Sixth Street on their way to the ferry building at the foot of the street, as that was the only way to conveniently get to the Starkist Cannery. Before World War II, it was also the way that the Terminal Island kids got to San Pedro High School before their families were shipped off to the internment camps.

The history of the once thriving commerce on Sixth and Seventh streets and Pacific Avenue is still embedded in the terrazzo entrances of some of the old stores. Some of the old store names of this era remain in a few of the historic buildings, but most of it is lost with only a few pictures of the boom years stored in the archives.

It wouldn’t be until the early 2000s that there was any serious effort to protect the historic facades of San Pedro and then the creation of historic preservation zones, one for the business district and the other residential — Historic Preservation Overlay Zone. There are some 20 HPOZs in the city of Los Angeles since the passage of the Mills Act in 1972 — a policy change that coincided with the demolition of Beacon Street. The Mills Act legislation grants participating cities and counties the authority to enter into contracts with owners of qualified historic properties who actively participate in the rehabilitation, restoration, preservation, and maintenance of their historic properties. A list of districts and resources can be found at the LA City Planning website.

However, the idea of LA actually having a “planning department’ is kind of an oxymoron as there are plans for every part of this city, sometimes two or three overlapping ones, but if you’ve lived here for any length of time you probably don’t have a clue unless you pulled a building or conditional use permit to open a certain kind of business. As our friends down at the Channel Street Skatepark learned the hard way, the city is awash in bureaucracy that makes it nearly impossible to plan anything creative unless you have an army of consultants, lawyers, lobbyists and engineers.

The fact of the matter is that Los Angeles doesn’t really have “a plan.” It has hundreds of plans, thousands of studies, and departments and bureaus each with their own rules and regulations. It’s enough to make your head spin. But how else are we to run a city of 4 million you might ask? Well the best solution is to have a local office for every department of the city in each of the districts’ city halls. In other words, decentralize the power structure.

Even though the city is divided into 15 districts of about the same population, there are common traits shared between all of the neighborhoods — particularly those neighborhoods with housing stock that was built during the boom years between the great wars. Most of their old business districts are of the same vintage as the stock in San Pedro and they have all suffered some of the same socio-economic problems that came with the loss of good middle class jobs and rising property prices. People who are old enough or lucky enough to have purchased property 20, 30 or 50 years ago are now millionaires on paper. Not that it would do a lot of good for them. Where are they going to go…Texas?… Idaho?

The saving grace in the San Pedro Bay communities is the prevalence of union jobs either at the ports or in city government. Yet only 46% of people in LA own their own homes, and in the Harbor Area I believe it is less, which is below the national average.

So, getting back to my main point about historic preservation and the current inebriated rush to tear down the old and build more housing, while losing sight of the jobs being eliminated by automation, what will Los Angeles become if it can’t retain good middle-class jobs and continues to build rental apartments with the aesthetic of Soviet worker housing? The unique neighborhoods of Los Angeles will lose their character, the community fabric will tear and there will be a growing disparity between the haves that own property and those who don’t. Rental housing has become a commodity driven by hedge fund investments, that’s unaffordable, and real estate ownership for the common person is declining as a path to the American Dream.

We’ve already seen the beginnings of this rupture following the battle over homelessness at Echo Park and Venice Beach and the uprising at City Hall over the anti-camping ordinance.

It kind of all comes down to answering the question, to whom does this city belong… the billionaires and corporations or the workers? The November election in LA will be pivotal in settling this question. The choice couldn’t be clearer — the billionaire Rick Caruso or the one-time community organizer Rep. Karen Bass.

The last guy who told us he was a billionaire as he ran for political office will soon end up in jail. Bass will likely come out ahead in the end, but can she or anyone else actually make the bureaucracy of Los Angeles work for the people? That remains to be seen as the corruption of corporate money at the city council seems to speak louder than all the votes of the citizens, no matter what neighborhood you live in.

The ghosts of old Beacon Street may come back to haunt us in ways we have yet to understand.

(James Preston Allen, founding publisher of the Los Angeles Harbor Areas Leading Independent Newspaper 1979- to present, is a journalist, visionary, artist and activist. Over the years Allen has championed many causes through his newspaper using his wit, common sense writing and community organizing to challenge some of the most entrenched political adversaries, powerful government agencies and corporations.)