CommentsWORKER RIGHTS - Some of the lowest wage workers are getting their livelihoods stolen by their own employers.

Employers deny workers overtime premiums, ask them to work “off the clock” or take their tips.

In California, workers lost nearly $2 billion from not being paid the minimum wage in 2015, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank.

Most often the victims of wage theft are women, immigrants and people of color, researchers say; many work in restaurants, construction, hotels, car washes, garment businesses, farms, warehouses, and nail salons. These workers are among those who bore the brunt of job losses during the pandemic and have the most ground to make up.

For years, California’s lawmakers have tried solving the wage theft problem by strengthening labor laws. Most workers who file wage theft claims wait months or years before getting a resolution; only a fraction who prevail get repaid lost wages.

Usually no one goes to jail for the theft.

Last year California made most wage theft a criminal offense. It also did away with the garment industry’s system of paying workers by the piece instead of by the hour. Now lawmakers are considering creating a statewide council to set wage and work conditions for the fast food industry. Here’s what you need to know about wage theft in California.

State officials list many ways employers steal workers’ money. Here are some common wage theft practices.

The Economic Policy Institute has cited other examples, such as an employer taking illegal deductions, confiscating tips or failing to pay tipped workers the difference between their tips and minimum wage, and misclassifying employees as independent contractors to pay a wage lower than the legal minimum.

How Big is the Problem

One way to look at it is how much workers try to recover in unpaid wages.

Last year California workers filed nearly 17,000 claims totaling more than $300 million in stolen wages, according to a database provided by the Labor Commissioner’s office. That may be an undercount; the office’s public web site indicates as many as 19,000 claims filed last year. State officials haven’t explained the discrepancy.

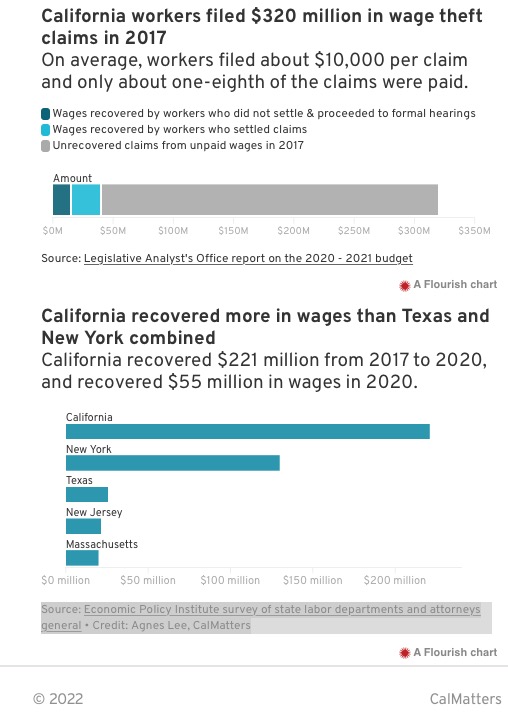

Either way, that’s down from prior years, when on average 30,000 workers annually claimed $320 million in unpaid wages, the office told the Legislative Analyst’s Office in 2020. Workers recovered about $40 million, or one-eighth, of those claims, the LAO said.

(Alejandro Lazo, Jeanne Kuang, Lil Kalish, Agnes Lee, and Erica Yee are reporters for CalMatters where this story was featured.)