CommentsACCORDING TO LIZ - Sacramento and its Department of Education have been blamed for the failing literacy of California children, money has been poured into studies but there has been little observable improvement.

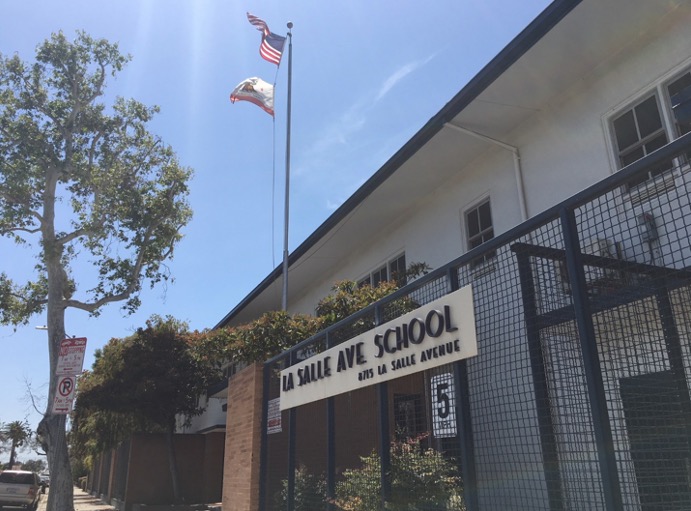

On December 5, 2017 the advocacy law firm Public Counsel representing students and teachers from three poorly-performing schools - La Salle Avenue Elementary in Los Angeles, Van Buren Elementary School in Stockton, and the charter school Children of Promise Preparatory Academy in Inglewood - sued the State of California in Los Angeles County Superior Court for failing to live up to its obligation to teach basic reading in Ella T. v. State of California.

Pursuant to state-established standards, English language proficiency at these three schools were, respectively, for the prior school year 4%, 6%, and 11%; only eight out of the 179 students tested at La Salle Elementary met California standards.

The suit argued that the ability to read is foundational for all education, which is a civil right under the state’s constitution. And the court agreed.

“Once you get behind, if there's no intervention, there's no catching up. The level of the work is getting more intense and multiplied at every level.” - David Moch, retired LAUSD elementary school teacher

In February of 2020, the California Department of Education, the State Board of Education, and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond agreed to provide resources to improve literacy outcomes for the state’s lowest-performing schools, and adopt a holistic approach to literacy.

Block grants were to be used to determine root causes of low student achievement in each of the targeted schools, to develop and implement customized three-year literacy action plans, and invest in evidenced-based practices to improve literacy such as individual coaching, additional teacher’s aides and professional development.

The settlement also mandated money to strengthen the state’s literacy infrastructure and training opportunities, and to create a Blue Ribbon Commission on exclusionary discipline, and a public event to discuss alternatives to harmful disciplinary practices, since it is very clear that removal from the classroom and suspensions do nothing to help any child’s learning.

To what extent the $53 million provided for in the settlement and administered by the Sacramento County Office of Education has succeeded may never be determined, given the teaching traumas of the past two-and-a-half years.

However, we can be certain that literacy across the state has probably not improved.

Education is essential, especially today.

“We need citizens that can read. We need citizens that can vote,” said David Moch, a retired Los Angeles teacher who was part of the lawsuit.

How can kids succeed in other courses if they can’t read well?

A year ago, State Superintendent Thurmond established the Statewide Literacy Task Force, with the goal of achieving universal literacy in third grade by 2026. Dr. Frances Gipson, former Chief Academic Officer at Los Angeles Unified School District who launched a literacy program called Primary Promise was named staff coordinator for the task force and literacy effort.

And it’s a challenge.

In about 8% of the state’s 10,558 schools, 75% of students can’t read at grade level.

Half of California’s third graders, including two-thirds of Black students and three-fifths of Latino students, can’t read at grade level.

But right now, Sacramento certainly isn’t prioritizing early literacy. In fact, this spring it slashed hundreds of millions from Newsom’s education budget.

More recently, Assembly Bill 2774 which would have put additional money into California education for the poorest performing students was pulled because Newsom was afraid of running afoul of Prop 209 which bans funding based on race.

Surely this is not a question so much of race but of academic performance – whether they are black, red or green, all our children deserve a quality education.

Not addressing the issue will only widen the divergence between success ratios for low-income and Black and Latino students and for their whiter and wealthier peers.

And wealth is a major factor. Black students comprise less than six percent of the state’s almost 6 million students but an estimated 70% of them are from low-income families. However, even low-income white students outperformed non-low-income Black students in math.

Too often there’s a plethora of related issues as well. In Reign of Error a critical look at the American educational system by Diane Ravitch, many children have already fallen behind their contemporaries even before they enter school due to lack of access to being read to, to proper health and dental care, and to nutritious food and a safe place to live.

Prior to the pandemic, only 33% of Black students met or exceeded English language arts standards, and only 21% met or exceeded math standards on the state tests, compared with 51% in English language arts and 40% in math for all students in California. Even those numbers are shocking.

Eliminating these discrepancies will be a daunting and long-term challenge.

And is the newly installed superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District up to the task?

Alberto Carvalho coasted in from a Florida school district that was the top performer in the National Assessment of Educational Program assessment of fourth grade reading and math. LAUSD was fifth from the bottom out of the 27 urban districts. He faces an entrenched bureaucracy from when the school district served 50% more students sucking money from the education of those who remain.

Additionally, controversy still rages over how to teach reading.

In recent years, a push to implement evidence-based reading instruction, focusing more on phonics and structured literary, has caused schools around the country to re-evaluate their approach with startling results.

If Mississippi can see fourth-grade reading scores improve from 39th to 2nd between 2013 and 2019, can California do any less?

How can Californians hold the state, the Department of Education, schools and teachers accountable?

Do the students of California need to sue the state again?

(Liz Amsden is a contributor to CityWatch and an activist from Northeast Los Angeles with opinions on much of what goes on in our lives. She has written extensively on the City's budget and services as well as her many other interests and passions. In her real life she works on budgets for film and television where fiction can rarely be as strange as the truth of living in today's world.)