CommentsLGBTQ HISTORY - The round face of a cartoon cat—big eyes, earnest smile—still hangs off the front façade of the Black Cat in Silver Lake.

Today, it peers out from above the kind of gastropub where you can order a $16 cocktail, easily fitting in with this gentrifying part of Sunset Boulevard, once known as a working-class Latino neighborhood and gay enclave. By the end of this year, the space next to the Black Cat is slated to become a Shake Shack, joining the likes of luxury supermarket chain Erewhon a block west.

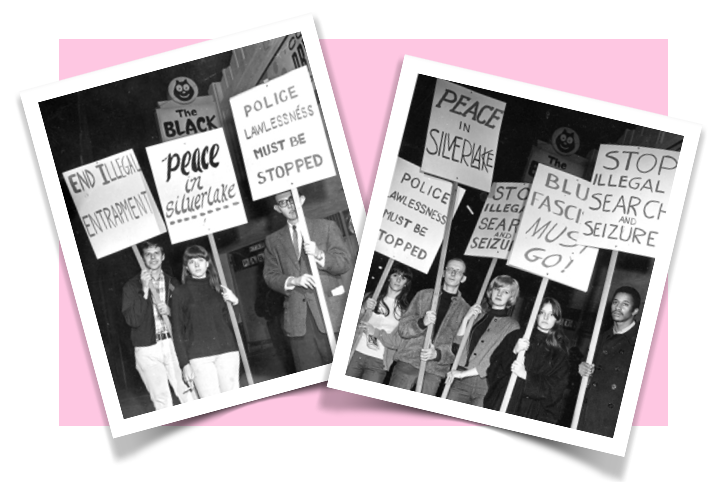

Fifty-five years ago, though, photographs captured a different Black Cat, a gay bar that inspired civilians to gather under those large feline eyes and protest the unfair treatment of LGBTQ people. The photographs unsettle the mainstream LGBTQ rights narrative that begins at Stonewall and ends in marriage equality. They place Los Angeles at the locus of the fight, in addition to other cities like New York and San Francisco. They anchor the gay bar not only as a place that once scandalized society with the tenderness patrons showed one another, but also as a site of political struggle.

At the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve 1967, the mood at the Black Cat was joyous: a trio of Black women called the Rhythm Queens sang a rock version of “Auld Lang Syne,” balloons fell, and imbibing bargoers, some in drag, embraced and kissed—men kissing men, women kissing women—as is wont on that night, at that hour.

Few knew that a dozen plainclothes cop scattered about the bar —part of what were called vice squads—were about to inform their uniformed partners outside to come in, raid the bar, and arrest its patrons for dancing and kissing one another, criminalized as “lewd” conduct.

What happened next has since been characterized as a riot, but those who were there at the Black Cat describe an assault, a sudden and violent raid with little resistance. Uniformed police “rushed in and began to swing billy clubs, tear down leftover Christmas ornaments, break furnishings, and beat several men brutally,” one witness later recalled. Fourteen people, patrons and employees, were forced face down on the sidewalk and arrested. Police chased two men down the street to New Faces, another popular gay bar, and beat the owner, a woman named Lee Roy. They had mistaken her for a man in women’s clothing, having heard the name “Leroy.” When a bartender stepped in to protect her, they beat him as well, until he lost consciousness.

The New Year’s raid on the Black Cat came at a time when every state in the country had anti-sodomy laws and on the heels of anti-gay McCarthyism known as the Lavender Scare, a witch hunt that had reverberations in the upper echelons of the nation—President Lyndon B. Johnson’s closest aide, Walter Jenkins, was even arrested on a “morals charge” and forced to resign in 1964. And in Los Angeles, the Black Cat raid was one of many documented instances when the LAPD harassed, entrapped, and assaulted LGBTQ people. Often these raids resulted in plea deals, or a fine running from $1,000 to $1,500. But that wasn’t the case at the Black Cat. Six of the people arrested there were tried by jury and found guilty of lewd conduct. Two had to register as sex offenders.

Gay Angelenos’ anger and frustration toward the system had already been reaching a breaking point. Just two years prior, there had been an uprising at a popular 24-hour diner downtown called Coopers Do-nuts, complete with a crowd throwing donuts at arresting officers. What happened at the Black Cat now inspired a new coalition of gay rights organizations, helmed by Personal Rights in Defense and Education (PRIDE), and other groups facing harassment by police—hippies, anti-war activists, club owners targeted by curfews—to join together in protest two months later, on February 11, 1967.

The gathering of several hundred people marked a watershed moment for the gay rights movement—one of the first times LGBTQ people made such a large public demand for recognition, and a promise to push back against police harassment and repression. The demonstration reframed the struggle as a fight for the civil rights of gay people and other minority communities who faced police abuse.

The gathering of several hundred people marked a watershed moment for the gay rights movement—one of the first times LGBTQ people made such a large public demand for recognition, and a promise to push back against police harassment and repression.

Although gay activists intentionally left the word “homosexual” off of their signage to appease protesters who were not prepared to take an explicitly gay rights stance, organizer Jim Kepner gave a rousing speech that called for gay people to stand up as gay people. Kepner called for building a coalition, with Black and Latino communities across L.A., to fight police violence, but found it unacceptable that even in struggle LGBTQ people weren’t recognized as such: “[T]he time has come when the love that dared not speak its name will never again be silenced. We’ve been copping out to society for centuries.”

Raids targeting gay people in Los Angeles continued after the Black Cat, and so did resistance. But the histories of this civic protest are largely neglected in the mainstream origin story of gay rights, which usually starts with the demonstrations that rocked New York City’s Stonewall Inn in 1969, and forgets altogether that it took moments like the raid at the Black Cat to make Stonewall happen. It’s a reminder that the most important framing in struggles for liberation should not be “we did it first” but rather “we did it, too.”

Today, the Black Cat serves as a visible monument to a pre-Stonewall past. In 2008, working with longtime Silver Lake resident and activist Wes Joe, the Los Angeles Historical Conservancy designated the Black Cat a Historical-Cultural Monument for its “early and significant role in the LGBTQ civil rights movement.” The group installed a plaque that sums up the progress wrought: gay people won the right to patronize bars openly, to no longer suffer legal or labor repercussions for their sexuality, and, eventually, to participate in the institution of marriage. The plaque also reminds us that Silver Lake was the “gayborhood” before West Hollywood’s “Boystown,” populated by leather and dance bars, and the fruits of a good, if unfair, fight.

The site’s profile was heightened in 2017, when city officials and gay rights organizers reenacted the historic protest on its 50th anniversary. Mayor Eric Garcetti and several officers from the LAPD attended. One of the officers approached activist Alexei Romanoff, who had helped organize the 1967 protest, and thanked him. It was a moment that showed how far things had come, Romanoff later said.

The deep irony is that this recognition comes at a time when the space no longer identifies as a “gay” bar. In some way, the Black Cat in its current resurrection stands as a metaphor for a movement that made long strides toward equality only to have seemingly dead-ended in marriage.

Back in 1967, the media didn’t cover the demonstration outside the Black Cat, but unknown participants took photographs, which are now housed at the ONE Archives Foundation, the oldest operating LGBTQ organization in the United States, at the University of Southern California libraries. These rare photos help us begin to piece together a longer and more accurate history of the movement for gay civil rights.

Today, the Black Cat, too, displays these photographs of the protest, amid walls crowded with art. The images demand we think more deeply about what the struggle for gay bars was actually about, and what the struggle to preserve them means. Signs from 1967—“BLUE FASCISM MUST GO!” “POLICE LAWLESSNESS MUST BE STOPPED” “END ILLEGAL ENTRAPMENT”— echo the slogans calling to “defund the police” and “end police brutality” that echoed above the same street in 2020 after an officer murdered George Floyd and sparked nationwide protests.

The images beg the question of whether the new Black Cat could use its history to expand that fight. Could it become a site for political action against police brutality, “Don’t Say Gay” laws, anti-trans violence? The images ask what fight has been lost, now that the space is no longer so anchored to its queer history.

Outside, the ubiquitous cartoon cat may still hang, but its shadow these days is dark and elongated, stretching long and thinning out at its head—having mostly run its course.

(TALIB JABBAR is an associate editor at Zócalo Public Square where this article was featured.)