GELFAND’S WORLD-I can remember Greg Nelson, the spiritual godfather of the neighborhood council movement, referring to participatory democracy within the system. The term has a 1960s protestor sound to it, probably because one extreme form of participatory democracy came of age during that era and dwindled just as rapidly.

Those of us of a certain age remember the gatherings which attempted to function according to this idea of a true democracy, just one step removed from courteous anarchy. No yelling or screaming, but the gavel got passed around from one person to another over the course of a discussion.

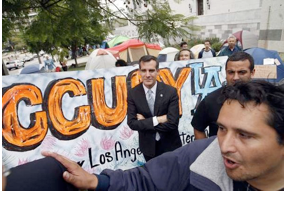

I think the closest thing we have had recently to ye olde participatory democracy came about during the Occupy encampments in front of the LA City Hall not long ago. Reports from the City Hall encampment mentioned the seemingly endless debates and votes on every which thing, apparently in the attempt to wring every semblance of authoritarianism out of the structure.

Our neighborhood councils have not gone in the same direction. As a cofounder of one of the councils, I would like to suggest that we could use a bit more of that participatory democracy in our neighborhood councils, and a bit less bossiness.

One curious contradiction that turns out not to be so contradictory: Greg Nelson never really liked enforcing Roberts Rules of Order on the neighborhood councils. He gave various reasons for feeling this way, but I would like to think that deep down, he was pulling for us founders to develop something as close as possible to a real democratic ideal in our functioning. (Greg: Looking forward to your response in the comments.) I, on the other hand, have been pushing for neighborhood councils to adopt Roberts Rules and for their boards to make themselves experts in their use.

I would like to try to explain why participatory democracy and Roberts Rules are potentially pretty close, and can get us about as near as we can go to that utopian idea of free form discussion leading to democratically achieved choices.

The way I am going to approach this argument is to consider one practice that goes against the ideal of participatory democracy. The example I wish to use is the periodic meeting that the elected City Council representative has with the presidents of the local neighborhood councils.

On the face of it, the concept makes some sense. The City Council rep cannot meet with everybody in the district at any one time. After all, there are a quarter of a million of us. So the City Council rep, wishing to demonstrate some fealty to the neighborhood council ideal, invites the presidents. The presidents speak of matters as they see fit, and once in a while, they report to the public a little of what transpired at the royal summit.

That, of course, does not fit with the guiding principle of our neighborhood council system, which is to bring the government closer to the people. By "the people," I think it is obvious that what is meant is all of us. Not just a few of our elected representatives, but all of us.

You might respond that it is simply impossible for a single City Council rep to meet with all of his constituents. That's obvious, but it's not a good counterargument. It is certainly possible for an elected City Council rep to come to a meeting that has 30 or 40 people and listen to comments. It is even possible for an elected official to come to a meeting that has more than a hundred people and entertain discussion. We saw it not long ago when City Attorney Mike Feuer hosted a public meeting in an auditorium at LA Harbor College and gave everybody a chance to talk. Sometimes he referred people to his deputies -- who were there -- and sometimes he handled comments and questions on his own.

The point here is that the people, in the plural sense, got their shot at participating in government.

That's a long ways from your typical neighborhood council meeting in which members of the public are given one shot at speaking to the elected royalty, and often enough, limited to 2 or 3 minutes. The chance for those same members of the public to be invited to the presidents' meeting is effectively nil.

In other words, the way we have formalized our chain of communication with the City Council rep -- the person who counts -- doesn't do anything for the free exercise of democracy. It's just a way of restyling what the city always did before, namely to give access to a few rich people, union leaders, and homeowners' association presidents, while the rest of us are left waiting at the back door.

{module [862]}

{module [662]}

The idea ought to be that access to government should become as broad as we can make it. We have about 1700 elected board members among our councils, but we only have 95 presidents. That limits access to government for the rest of the board members. It's even more so for those of us who aren't elected board members.

Participatory democracy, at least as I remember it, meant that everyone was equal, and that meant that everyone had an equal chance to speak. Admittedly, this often enough included the chance to waste other peoples' time. We don't have to go to that extreme in our neighborhood council meetings. We can limit board members and the public alike to their 3 minutes per speech. What we should not do is give board members more opportunities to speak than we give to members of the public. If the board members get to give 2 speeches on any one agenda item, then the members of the public should have the same opportunity.

Participatory democracy, at least as I remember it, meant that everyone was equal, and that meant that everyone had an equal chance to speak. Admittedly, this often enough included the chance to waste other peoples' time. We don't have to go to that extreme in our neighborhood council meetings. We can limit board members and the public alike to their 3 minutes per speech. What we should not do is give board members more opportunities to speak than we give to members of the public. If the board members get to give 2 speeches on any one agenda item, then the members of the public should have the same opportunity.

But we should also encourage neighborhood councils to relax the rules every once in a while, and invite some free form discussion on matters of importance. It can be done by holding a town hall type of forum, or simply by setting aside a certain amount of time for back and forth discussion among members of the public.

Here is where the defense of Roberts Rules comes in. Roberts Rules, at its heart, is the principle that every participant has equal rights. If the City Council rep wants to meet with a small number of people, then a neighborhood council meeting should vote on which people get to go as neighborhood council representatives. The neighborhood council reps can be chosen by the entire assembly, including the public and the board members, or the board can split the load between a peoples' rep and a board rep. In no case should one board officer get to hog the right to meet with the elected official.

I don't think I would like to see the old fashioned participatory democracy at each and every neighborhood council board meeting, because I don't want meetings to go on for 6 hours. But we can adopt a system in which all participants, board members and the public alike, can have rights and opportunities that are as equal as possible.

In practice, this precludes the elected president from unilaterally telling people, "I'm going to limit public comments to 2 minutes because we have a heavy schedule." That decision should belong to the entire board, after allowing for public comment. Likewise, the elected president should never unilaterally announce, "OK, I'm going to take 2 more comments." These sorts of decisions belong to the board as a whole, and if the board is in tune with the democratic ideal, it will consider the views of the public before doing anything to limit public participation.

Clearly, if you tend to agree with my philosophy, you will use Roberts Rules to make your neighborhood council as democratic as possible, rather than as authoritarian as possible. The advantage of having a robust Roberts Rules process is that it gives the lowly board member sitting at the end of the table the right to argue for the public's right to participate. Notice that it is easy to use Roberts Rules to defend public rights, just as it is easy to use Roberts Rules to overly limit those rights. There is an analogy with participatory democracy. Just as participatory democracy can be used to develop social movements, it can also be used to waste hours of peoples' time. The goal is to find the best elements of both systems.

Ideally, our elected City Council representatives should make time for open meetings where the public get to participate. In all other matters in which the City Council rep wishes to deal only with a small group of public representatives, the choice of who gets to participate should be made using an openly democratic process. The current process engaged in by most neighborhood council boards, in which power is held tightly by the board and public comment is restricted, should be replaced by something closer to that ideal of participatory democracy.

(Bob Gelfand writes on culture and politics for CityWatch. He can be reached at [email protected])

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 12 Issue 94

Pub: Nov 21, 2014