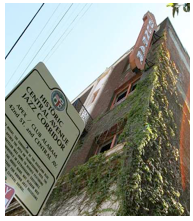

THE VIEW FROM HERE-Over the years I have repeatedly heard fond reminiscences of the Dunbar Hotel. I began to wonder what was so significant about this place. It turns out it holds great historic significance.

Built in 1928, it was named the Somerville Hotel until 1930 when it became the Dunbar. Few, perhaps, know that it hosted the first national convention outside the East for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) at which W. E. B. DuBois spoke.

Though Negroes (“Negro” and “colored” were the terms used back in the day) could perform in Beverly Hills and other upscale neighborhoods, they could not stay at hotels in those “whites-only” communities, so they found lodging for themselves along what became the Jazz Corridor on Central Avenue where the Dunbar was located.

This hotel emerged as a gathering place for Negro entertainers and a center for the jazz culture—people like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and countless others played their instruments like few others could.

Singers like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Billy Eckstine, Billie Holiday (Lady Day—love her music), Nina Simone (with her “Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees … Blood on the leaves”), and Lena Horne belted out their vibratos and made you want to cry or laugh or moan.

The writer, Langston Hughes, was also something of a fixture there (“Mother to Son” and “Life Ain’t Been No Crystal Stair” are unquestionably some favorites).

The Sommervilles themselves are a part of the rich Black heritage of Los Angeles. John Alexander Sommerville became a dentist and was the first Negro to be graduated from USC. He served in many capacities, including terms on the LA Police Commission. His wife, Vada, also received her degree in dentistry. Together they built (with the help of many supporters) what became the Sommerville Hotel, built by Black contractors and laborers. The couple were veritable movers and shakers in the community, and, among other actions, were responsible for opening the first NAACP chapter in Los Angeles.

The Sommervilles later renamed their hotel, the Dunbar in honor of Paul Laurence Dunbar (one of my favorite poets who wrote, among many others poems, “Little Brown Baby,” a piece I loved to read to my students who always savored those moments). Today the Dunbar as a hotel does not exist, but regardless of what transpires in the future, the history of that edifice remains! Under the guidance of former City Councilmember Jan Perry, the location has been transformed into Dunbar Village where an intergenerational community is being wooed: affordable housing for seniors and families and jobs for young people.

Jazz was and is transformative. As notes metaphorically wafted through the air from the Dunbar so long ago, white folks began descending upon that location (just as so many had gathered at the Cotton Club in Harlem). Soon white musicians were taking up the beat and became celebrated jazz artists in their own right. People like Bix Beiderbecke, Pee Wee Russell, The Rhythm Kings; later Les Brown and the Band of Renown, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller (I love “Little Brown Jug”), Gene Krupa; more recently The Jazz Crusaders, Dave Brubeck, Chuck Mangione, and, of course, that skinny Jewish fellow, Kenny G.

Jazz was and is transformative. As notes metaphorically wafted through the air from the Dunbar so long ago, white folks began descending upon that location (just as so many had gathered at the Cotton Club in Harlem). Soon white musicians were taking up the beat and became celebrated jazz artists in their own right. People like Bix Beiderbecke, Pee Wee Russell, The Rhythm Kings; later Les Brown and the Band of Renown, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller (I love “Little Brown Jug”), Gene Krupa; more recently The Jazz Crusaders, Dave Brubeck, Chuck Mangione, and, of course, that skinny Jewish fellow, Kenny G.

In 1945, near the end of World War II, Dizzy Gillespie came out from New York with his band. Charlie Parker, the Yardbird, accompanied him. Together they created what became modern jazz. They played at Billy Berg’s Hollywood Nightclub which promoted these sojourners in a new form of entertainment and aired their music on radio; at the same time Dial Records made their albums. The LA Philharmonic hosted jazz concerts in the 1940s. Jazz music shops proliferated. Leonard Feather [who in later years used to critique the Playboy Jazz Festival which has been held yearly at the Hollywood Bowl for over 40 years (a must-attend event!)] used to report on the underground jazz movement.

The West Coast Jazz Scene was created—located in Los Angeles (as well as San Francisco). It was more of a “cool jazz” rendition as compared to the more frenetic style of New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Other jazz musicians developed a harder sound called California Hard. Central Avenue soon attracted more “bebop” bands than anywhere else west of the Mississippi.

Back in the ‘60s, I remember listening to Willie Bobo at the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, a place now appealing to a variety of music aficionados—the sounds of reggae and a host of other styles abound. The Strand in Redondo Beach used to offer the same melodious flavors. Birdland West in Long Beach was another favorite location (my husband and I fondly remember swaying to the resonating sounds of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers).

Although some of these places only hold a place in our mental history, others are newer on the scene: The Catalina Bar and Grill on Sunset is a big draw; The Blue Whale Bar in Little Tokyo with its avant-garde offerings; The Baked Potato in Studio City, and Vibrato on Beverly Glen Circle—to name only a few.

When all is said and done, What is jazz? It was born out of ragtime and blues and the pain of slavery and segregation, of Jim Crow and the Black Codes. It is truly American music. So when it seems to distort pitch and timbre, it is not by accident. There is genuine anguish there—something not to be forgotten, something to be remembered, a part of the soul to be passed on from generations past to generations future. Improvisation and hard-coursing rhythms are its foundation. Listeners tremble to their very depths. It is mixed with a passion and humanity few other forms express.

At first blush, jazz may not be for everyone, but it is music which we must explore and to which we ought to expose ourselves. Like so many other new things, it can (in all its facets) grow on even the most uninitiated listeners. I fear if we do not pass this genre on to the next generations, it may become a relic in music history—something like the clavichord is to the piano. Generally we see that the overwhelming number of jazz concert-goers are older people. We need to share this beautiful part of our culture with younger ears as well.

Cool jazz. Hot jazz. Black musicians. White artists. An amalgam of styles and performers. We owe it to ourselves, in one way or the other, to become part of that fabulous LA jazz scene!

(Rosemary Jenkins is a Democratic activist and chair of the Northeast Valley Green Coalition. She also writes for CityWatch.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 11 Issue 94

Pub: Nov 22, 2013