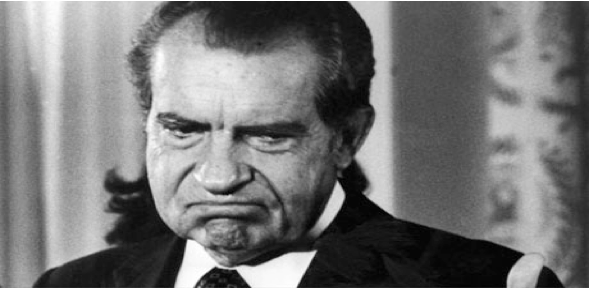

VOICES FROM THE PUBLIC SQUARE - In the summer of 1945, Richard Nixon, born a hundred years ago today, was a Navy lieutenant with a law degree and an uncertain future. So it was a thrilling stroke of luck when he got a chance to run for Congress. In the clubby world of Republicans in California, it meant a lot to know someone, and someone on a local search committee knew about Dick Nixon.

The Republican goal in the 12th Congressional District, which encompassed such small towns as Whittier, Covina, and Pomona, was to unseat the Democrat, Horace Jeremiah (Jerry) Voorhis, a well-liked five-term incumbent. Nixon’s champion on the search committee was a family friend, a Whittier bank manager named Herman L. Perry. “Lt. Nixon comes from good Quaker stock,” Perry told his colleagues. “By hard work he obtained a scholarship to Duke University law school. He is a very aggressive individual.”

Nixon was also a model postwar candidate: he was young (31), married, a veteran, and a local boy—born in Yorba Linda and reared in Whittier. And if no one knew much about his core beliefs (he wrote to Perry that “an aggressive, vigorous campaign of a platform of practical liberalism should be the antidote the people have been looking for to take the place of Voorhis’ particular brand of New Deal idealism”), perhaps it didn’t matter.

But all of Nixon’s youth, intellect, and energy—in particular a talent for debate—would not have been enough to defeat Jerry Voorhis, not even with Nixon’s willingness to hint that Voorhis harbored softness toward Soviet Communism. What helped most was the intercession of a newspaper, the Los Angeles Times.

Today, you often hear the complaint that too many shouting, cable-enhanced voices have drowned out sensible political debate, and perhaps that’s true. One tends to forget, though, that newspapers like the Los Angeles Times had one voice—and that it overwhelmed all the others. That voice was shaped by the paper’s political editor, Kyle Palmer, an undersized, charming, and deeply partisan man who’d been with the newspaper since 1919. It is no exaggeration to say that Nixon, for all his vaunted antipathy to the press, owed his career to this single journalist and his paper.

The late columnist Robert Novak described Palmer to me as “in effect a functionary of the Republican Party with the blessing of the Los Angeles Times and totally unashamed of it.” David Halberstam, in The Powers That Be, recalled a visit by The New York Times’ Turner Catledge, who asked Palmer about the paper’s unbalanced coverage. “Turner, forget it,” Palmer said. “We don’t go in for that kind of crap that you have back in New York—of being obliged to print both sides.” Greg Mitchell’s entertaining Privileged Son recounted many more such Palmer stories.

Kyle Palmer adored Richard Nixon—no other word quite suits. He had, I suspect, something of a political man-crush, an older man’s excitement at witnessing the birth and growing pains of a young candidate with enormous potential and an admiration for Nixon’s willingness to take on a whale like Voorhis.

Palmer’s enthusiasm was unflagging from the moment of their first meeting, in the spring of 1946, when Nixon, the novice office-seeker, started to meet newspaper editors, until Palmer’s death, of leukemia, in April, 1962, seven months before Nixon lost his race for governor of California. Palmer later recalled his vivid first impressions to Nixon’s friendly biographer, Bela Kornitzer: “Here was a serious, determined, somewhat gawky young fellow who was out on a sort of a giant-killer operation. But it wasn’t too long after he settled down that we began to realize we had an extraordinary man on our hands.”

By “we,” Palmer meant not only himself but the paper’s owners, the Chandler family, who likewise made no effort to hide their political leanings. When Nixon visited the Times, Palmer escorted him into publisher Norman Chandler’s office. “His forthrightness, and the way he spoke, made a deep impression upon me,” Chandler told Kornitzer, “and so—after Nixon departed—I told Mr. Palmer: ‘This young fellow makes sense. He looks like a comer. He has a lot of fight and fire. Let’s support him.’”

Nixon was suitably appreciative: “After all, I was nothing at the time, a small-time lawyer just out of the Navy,” he told Kornitzer. “The support was tremendously important in assuring my nomination for Congress.”

That was a considerable understatement. To use newspaper parlance, Palmer worked for both church and state. He oversaw the Times editorial page and directed political reportage for the news pages. He also wrote an unsigned column called the “Watchman.” All of these considerable resources were placed behind Palmer’s favored candidate.

“Richard Nixon is giving … Jerry Voorhis the fight of his life,” Palmer wrote in late May 1946, bringing what was surely news to many Southern Californian voters who had not yet heard of Richard Nixon.

A day later, an unsigned “Watchman” column, also written by Palmer, stated that “Nixon is about the best candidate the Republicans have dug up in years, but unless they get out and hustle for him, push doorbells, talk him up and get the votes out they might as well put up a bale of hay.” David Halberstam, as he followed the transition of the Times into an era of distinguished journalism, noted that Palmer was the only journalist who always had access to Nixon—and that their relationship was close to that of a father and son.

Nixon in 1946 was not a polished candidate. “He has terrifically large feet and we had trouble getting a pair of shoes that was big enough for him,” one party leader recalled. He was awkward, even shy—divorce cases with all their marital details embarrassed him. But as a candidate he showed surprising fierceness. He lured Voorhis into several debates and sprung on him the wounding accusation that a Voorhis political action committee was infested with Communists. In the end, Nixon defeated Voorhis with 56 percent of the vote. When he ran for re-election in 1948, he was barely opposed.

By the fall of 1949, Nixon, to the dismay of some of his own advisers, was thinking about running for the Senate against very long odds. He was encouraged by Palmer, and not surprisingly the Watchman reported that “friends” of Nixon were saying that “Nixon is in the picture.”

After Nixon declared his candidacy, Palmer wrote, among other things, “Nixon is young enough to be old, and wise enough to be prudent and his perceptive qualities are exceptional. In fact the flattering references which our fathers formerly made to an exceptionally promising junior—that he had an ‘old head on young shoulders’—applies with all its homely implications to this young man who grew up here, became a lawyer, went to war, and returned to win a spectacular victory in his first bid for public office.”

Palmer’s influence was less useful now, but several other important regional newspapers with Republican owners—notably Hearst’s San Francisco Chronicle and the Oakland Tribune of J.R. Knowland, whose son, William, had been appointed to the Senate by Governor Warren—gave Nixon their firm (if not quite Palmer-like) support.

Nixon’s U.S. Senate campaign in 1950—he ran against the attractive former actor and Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas—was famously nasty, much more so than the race against Voorhis; Senator Joe McCarthy was ascendant, and the Red issue had more bounce. Douglas had already won a nasty primary against the Los Angeles Daily News publisher Elias Manchester Boddy, whose surrogates portrayed her as an ally of leftist Congressman Vito Marcantonio. In the general election, Nixon insinuated, though he never quite said, that Douglas was not a loyal American.

Douglas never stood a chance. By this time, Congressman Nixon had also finished off Alger Hiss and had co-sponsored a bill to outlaw the Communist Party in America. That history helped attract the attention of General Eisenhower’s advisers in 1952, when they were selecting Ike’s running mate.

Kyle Palmer and his newspaper never flagged in their support or in their reluctance to print the “kind

of crap” that fairness and balance demanded. A Times editorial late in the campaign omitted the word “not” in a commentary which asserted that “Douglas, who though a Communist, voted the Communist Party line in Congress innumerable times.” Apologies and a correction followed, but by then it didn’t really matter.

What these elections really demonstrated was the power of dominant regional media outlets in local and state elections—in races for Congress, the Senate, the state house—all the places where presidential aspirants launch their careers. That’s where you see what might be called the “Kyle Palmer effect,” which has a lot more heft than any national TV personality on venues like Fox or MSNBC. Fox News Chief Roger Ailes probably knows who Kyle Palmer was, but he is no Kyle Palmer—and, as someone who presides over a national rather than local operation, never could be.

(That Ailes, according to Bob Woodward, once offered to use his network to lead General David Petraeus into the White House, is indicative more of Ailes’ hubris than his actual power.) To those who worry about the influence of Rupert Murdoch on our politics, I’d suggest that they relax and enjoy Fox News and worry instead about whether he’ll ever own the Los Angeles Times.

(Jeffrey Frank is the author of Ike and Dick: Portrait of a Strange Political Marriage, which will be published by Simon and Schuster in February. This piece was posted first at ZocaloPublicSquare.org … the daily ideas exchange.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 11 Issue 4

Pub: Jan 11, 2013